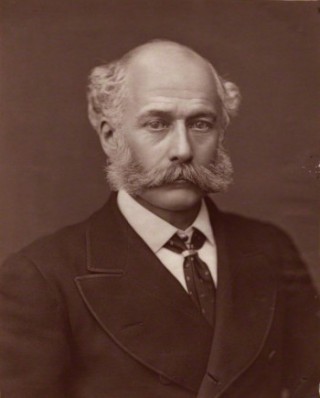

Thursday 28 March marks the bicentenary of the birth of Joseph Bazalgette – one of the most illustrious Victorians, but someone you may never have heard of.

Joseph Bazalgette

Think of Charles Darwin, Charles Dickens, Mrs Beeton, Alexander Graham Bell, Mary Seacole or Benjamin Disraeli – they all made their mark but it is the sound you hear every time you flush that is Joseph Bazalgette’s legacy. Bazalgette was the Chief Engineer with the London Metropolitan Board of Works and the man responsible for creating the sewerage system which still serves London today. Without Bazalgette life in London would have been a lot more pungent (even noxious), and you might well have died from typhoid or cholera.

To find out more I can direct you to The Great Stink of London: Sir Joseph Bazalgette and the Cleansing of the Victorian Metropolis, which tells the story of a London lad (Joseph was born in Enfield) and his work building a sewerage system fit for purpose. In Victorian London house drains emptied into sewers and then into the Thames. A growing population and the popular adoption of the flushing toilet had grossly overloaded a system that it would be kind to describe as ‘medieval’. In 1848-9 more than 14,000 Londoners died of cholera; in 1853 another 10,748. Something needed to be done and done urgently.

Exceptionally hot weather in the summer of 1858 exacerbated the situation further. The smell in London was so bad that Queen Victoria’s pleasure cruise on the Thames had to turn back, and the business of Parliament was interrupted when, despite curtains being soaked on the riverside of the House in lime chloride to mitigate the smell, rooms became uninhabitable. Rosemary Ashton’s cultural history One Hot Summer uses diaries and letters to report on how residents coped, and didn’t, with the truly awful situation.

Exceptionally hot weather in the summer of 1858 exacerbated the situation further. The smell in London was so bad that Queen Victoria’s pleasure cruise on the Thames had to turn back, and the business of Parliament was interrupted when, despite curtains being soaked on the riverside of the House in lime chloride to mitigate the smell, rooms became uninhabitable. Rosemary Ashton’s cultural history One Hot Summer uses diaries and letters to report on how residents coped, and didn’t, with the truly awful situation.

If you prefer your history in a fictional framework Clare Clark’s novel ‘The Great Stink’ tells the story of William May, who has returned from the Crimean War deeply damaged by what he has experienced. He finds work on Bazalgette’s sewer project but quickly becomes embroiled in the world of crime that lies beneath the streets. Clare is great at evoking the sights (and smells) of Victorian London. Sadly ‘The Great Stink’ is out-of-print in paper formats, but you can get the e-book, or your local library will be able to help.

Once you have a taste for Clare’s writing you won’t want to stop there. I recommend you try Beautiful Lies – there is not a whiff of sewers in this one. It is set in the year of Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee and tells the story of a woman dabbling in the new-fangled art of photography.

As Chief Engineer, Balzagette oversaw revolutionary works to create brick-lined, fully-enclosed sewers and pumping stations. The project was opened officially by the Prince of Wales in 1865, although it was not fully completed for another ten years. A man to think ahead, Bazalgette’s design created tunnels far bigger than those required to service the immediate need which meant that, even with London’s increased population density caused by tower block living, his sewer system still serves the city today.

A good general overview of the history of London sewers can be found in London Sewers. This well-illustrated little book also covers the appearance of sewers in fiction and film.

Phil Stride’s book The London Tideway Tunnel brings the story up-to-date and explores the latest development in the history of London’s sewers – the Tideway Tunnel Project. This £4.2 billion project to build a 25 kilometre tunnel under the Thames will ensure that Bazalgette’s legacy continues.

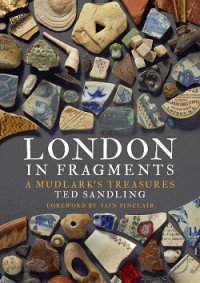

On a lighter (and less smelly) note, London in Fragments is an enchanting look at the history of London from a mudlark’s perspective. The original mudlarks were small children (and sometimes adults) who made their living scouring the banks of the river for anything they could use, repurpose or sell. Today’s mudlarks seek to build a picture of the past from the fragments they discover – anything from the bizarre to the beautiful. There are amazing pictures here of very special finds.

On a lighter (and less smelly) note, London in Fragments is an enchanting look at the history of London from a mudlark’s perspective. The original mudlarks were small children (and sometimes adults) who made their living scouring the banks of the river for anything they could use, repurpose or sell. Today’s mudlarks seek to build a picture of the past from the fragments they discover – anything from the bizarre to the beautiful. There are amazing pictures here of very special finds.

Alternatively, if you think your family has a personal connection to the river then look to My Ancestor was a Thames Waterman to find out how you can explore their colourful past.

Relevant reading supplementary to the subject is The Ghost Map by Steven Johnson (Penguin, 2006) about the 1854 cholera outbreak in London and how the city’s methods of water supply and sewage disposal contributed to the epidemic. Johnson is a superb writer and the history reads like a novel.

Very interesting I shall look up some of the books about Landon’s sewerage systems