The England cricket team’s 1981 tour of the West Indies did not get off to an auspicious start. The night before the beginning of the first Test at Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago, the Queen’s Park Oval pitch was sabotaged. The suspected culprits were supporters angered by the exclusion of Trinidad captain Deryck Murray from the West Indies team. Attendance at the match was also poor. British High Commissioner David Lane estimated that the ground was only 75% full for the opening two days, dropping to 15% for the remainder. Captained by Ian Botham, England eventually suffered an innings defeat. At least, Lane remarked, ‘the team created, I think, a good impression here for everything except the standard of their cricket’ (FCO 99/654).

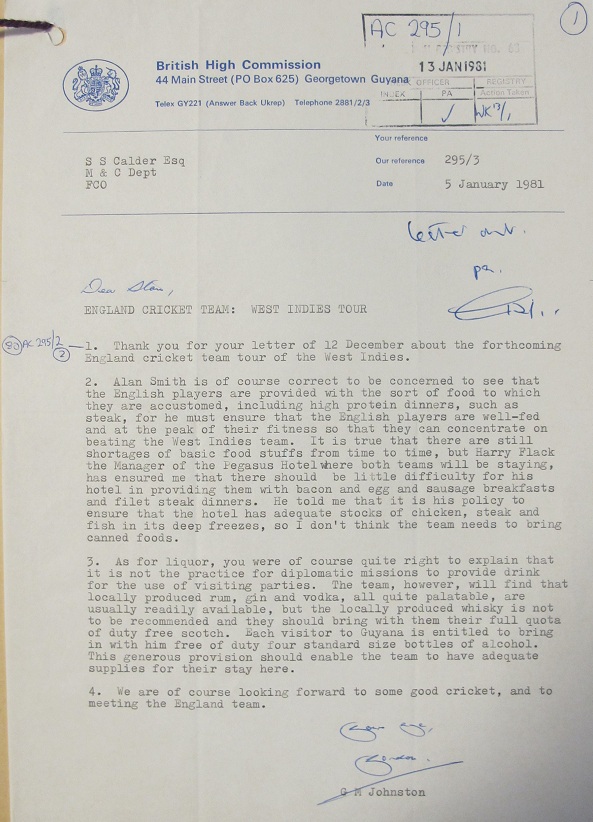

The second Test at Georgetown, Guyana was due to begin on 28 February, 35 years ago this weekend. The only concerns about the match prior to England’s departure had focused on the availability of food and drink. A Foreign Office official provided reassurance about culinary issues, but pointed out that ‘it is not the practice for Diplomatic Missions to provide drink for the use of visiting parties’. Nevertheless, he relayed the consolation from the High Commission that ‘locally produced rum, gin and vodka, all quite palatable, are usually readily available’. In contrast, ‘the locally produced whiskey is not to be recommended’, and the party was advised to make full use of their quota of duty free scotch (FCO 99/654).

The decision to call-up Robin Jackman as a replacement for the injured fast bowler Bob Willis put the match in jeopardy. A fine county season in 1980 – for which he was later named as one of Wisden’s Cricketers of the Year – had led to Jackman’s first Test call-up, at the age of 35. Although he did not play in the 1980 Centenary Test against Australia, he remained a logical addition to the England squad. The issue was that, in the absence of earlier international touring opportunities, Jackman had spent the British winters coaching and playing in South Africa and neighbouring Rhodesia.

Three days before the Georgetown Test was due to get underway, Britain’s High Commissioner to Guyana Phillip Mallet reported that ‘A squall has blown up over Jackman’. South Africa’s policy of apartheid was the subject of international outrage and efforts to isolate the country from sporting events. This was reflected in the 1977 Gleneagles Agreement, where Commonwealth leaders vowed ‘to combat the evil of apartheid by withholding any form of support for, and by taking every practical step to discourage, contact or competition by their nationals with sporting organisations, teams or sportsmen from South Africa’ (PREM 16/1883).

The Guyanese government took a particularly strong line on sporting relations with South Africa. High Commissioner Mallet wrote to the Foreign Office that ‘We must hope that the Guyanese can get off the hook on which they have impaled themselves’. He suggested helping them by emphasising the multi-racial nature of the Test match, especially given that the tourists’ squad included Barbados-born Roland Butcher, England’s first black player. At the same time, Mallet also warned Guyana’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, Rashleigh Jackson, that declaring Jackman a prohibited immigrant on the grounds of his South African contacts might lead to the departure of the whole England team and the cancellation of the Test (FCO 99/654).

The topic of Jackman’s presence in Guyana was exacerbated by domestic political sensitivities. In June 1980, the historian and political activist Walter Rodney, an opponent of President Forbes Burnham, was assassinated by a car bomb. The Caribbean News Agency broke the details, prompting Guyana’s withdrawal from the organisation. Alan Payne of the Foreign Office’s Mexico and Caribbean Department suggested that the Guyanese were prepared to overlook the links between the England touring party and South Africa ‘until Burnham’s old adversary, the Caribbean News Agency (CANA) took delight in drawing attention to those links’ (FCO 99/655).

Speculation as to future of the match, and even the series, began to swirl as the publicity of Jackman’s connections to South Africa increased. Commonwealth secretary-general Shridath Ramphal – a former foreign minister of Guyana – intervened in an attempt to calm the situation, while the matter was even raised at Prime Minister’s Questions on 26 February. The same day, however, High Commissioner Mallet reported the Guyanese government’s decision to revoke Jackman’s visa. With the England Cricket Council unwilling to field a team under such circumstances, the Test match was cancelled. Reflecting on the events in a long letter to the Foreign Secretary on 6 March, Mallet concluded that ‘There were principles at stake that could not be avoided’, adding that ‘in the last resort there was an emotional issue, that England should not be pushed around by a tin-pot quasi-dictator’ such as Burnham (FCO 99/654).

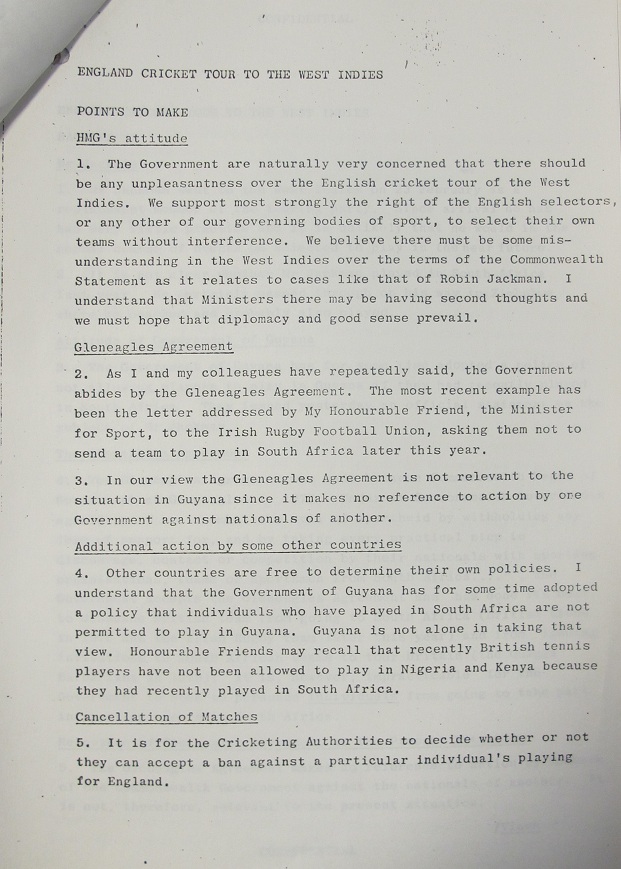

With the entire tour in jeopardy, attention turned to Barbados. From Bridgetown, Stanley Arthur reported on 28 February that he believed the government ‘wish to find a positive solution to the problem foisted on them by Guyana’ (FCO 99/654). The Barbadian public favoured the continuation of the series, as did opposition political figures. Arthur also thought it unlikely that Antigua would wish to cancel the first test match due to be played on the island. Back in London, contingency plans were made lest the tour be cancelled. A Cultural Relations Department background paper advocated the line that while the government regretted the action, ‘we continue to support the right of the English selectors to select their own team, based on merit, free from external constraints’ (FCO 13/1205).

The governments of Antigua, Barbados, Jamaica and Montserrat met on 3 March. The resulting statement highlighted the complexity of the ‘third party principle’ – the issue of individuals acting alone – but accepted that this fell outside of Gleneagles and therefore allowed for the continuation of the tour. Andrew Turquet from the High Commission in Barbados described ‘an almost audible sigh of relief when it was learnt that the tour was still on’. He continued: ‘the main thing at the moment is that England are playing cricket (albeit badly) and the tour has been saved’ (FCO 99/654).

The third Test therefore went ahead as planned. Jackman finally made his Test debut, taking three West Indies wickets for 65 runs in the first innings, and two for 76 in the second. He was unable to prevent England from succumbing to another heavy defeat, however. He also featured in the fifth Test at Sabina Park, Jamaica, which drew the ground’s highest ever attendance despite some appeals to cricket fans to boycott the game. Jackman ‘endeared himself to the crowd by his good humour’ (FCO 99/655).

With this match and the fourth Test ending in draws, England lost the series 2–0. Jackman’s Test career came to an end the following the summer. By then he had played in a total of four matches, taking 14 wickets at an average of just under 32 runs. He went on to work as a commentator in South Africa at the conclusion of his playing career.

Although it is referred to as the England cricket team they actually play under the England and Wales Cricket Board rather just England. It is difficult to separate apartheid and the Gleneagles Agreement from the lack of action by Margaret Thatcher’s Government against South Africa, especially over Nelson Mandela as noted by the recent release of a file from the FCO on ‘The case of Nelson Mandela’.

Thanks for your comment, David. The England and Wales Cricket Board was only established in 1997, replacing the Cricket Council mentioned in the post. (It also assumed the responsibilities of the Test and County Cricket Board and the National Cricket Association.) Recent releases relating to British policy towards South Africa can be found in PREM 19/1965-70.