Friday 18 May 2018, 18:30

Friday 18 May 2018, 18:30

Suffrage 100 – Archives at night: Law breakers, law makers

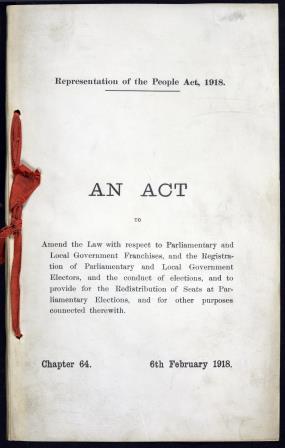

On 6 February 1918, 100 years ago, the Representation of the People Act 1918 received Royal Assent and came into force, providing (some) women with a vote in Parliamentary elections for the first time.

(The National Archives is commemorating this and the suffrage movement on our dedicated Suffrage portal).

Cover of the Representation of the People Act 1918. Catalogue reference: C 65/6385

Receiving Royal Assent and passing into the statute book and the law of the land is achievement for any Bill (draft law) presented to Parliament. It’s often a culmination of months of scrutiny and debate over every one of its proposed clauses and measures, and the political wrangling that takes place as a government drafts a law and considers whether they have the support in Parliament to pass it.

(If you’re interested in how law is made in the UK, I would recommend UK Parliament’s excellent guide here.)

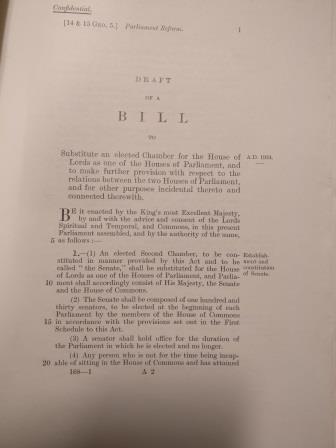

A dropped Parliamentary Bill to replace the House of Lords with an elected Senate, 1924. Catalogue reference: AM 4/28

Negotiating this parliamentary obstacle course is tricky enough for most laws – but Bills aimed at reforming the election and makeup of Parliament have a particularly chequered and tumultuous history.

The records of the Parliamentary Counsel, held at The National Archives under the catalogue reference AM, contain many examples of these casualties of constitutional reform – meticulously drafted Bills that fell by the wayside.

Extending the parliamentary franchise (the rule about who can vote) had been a contentious issue for a long time. One hundred years before the 1918 Act very few people had the vote. Campaigns for suffrage (although not usually women’s suffrage) were often suppressed by the state. Even the mild measures of the 1832 Great Reform Act (votes for some of the middle classes, more equal seats for MPs) took three attempts and a general election to get through Parliament. After further reform Acts in 1867 and 1884, 40% of adult men did not have the vote, and no women did.

An article from the Manchester Observer newspaper, 1819, from female reformers advocating for parliamentary reform. Catalogue reference HO 42/190 folio 11

However, by May 1917, when the Representation of the People Bill began to be discussed by Parliament, the political weather – at least for working men – was quite different.

Home Secretary George Cave introduced the Bill, claiming it would add 2 million men to the electoral register. He happily noted that, while in times gone by such a measure might have caused a tumult in the House, ‘To-day the proposed addition excites no emotion whatever, except a feeling of satisfaction that, by making this addition, we shall approach nearer to the ideal of representative Government, namely, to make Parliament a mirror of the nation.’[ref] Hansard, House of Commons Debates, 22.05.1917, Volume 93, columns 2134-2135[/ref]

One ‘thorny subject’, three sub-clauses

However, Cave did not have the same sunny confidence in Parliament’s progressive nature when it came to a ‘much more thorny subject … the extension of the franchise to women’.[ref] Hansard, House of Commons Debates, 22.05.1917, Volume 93, column 2135[/ref]

Despite its spiky nature, provisions for women’s suffrage only actually occupied a very small part of the Act’s 159 or so pages, being in the main part limited to three sub-clauses under schedule 4 of the Act (which you can read here).

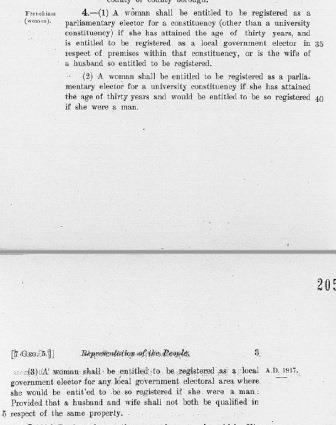

A draft copy of the clauses giving votes to women presented to Cabinet in May 1917, before the Bill entered parliament. Catalogue reference: CAB 24/12/55

When the draft of the Bill was originally shared by the Colonial Secretary with the rest of Cabinet in early May 1917, it set out to provide women the vote in three instances.

- A woman would be entitled to be a parliamentary elector if she had reached the age of 30 and was entitled to vote in local government elections, or was the wife of a man entitled to vote in local government elections.[ref]Entitlements to vote in local government elections were based on property qualifications – householders who rented or owned property and paid rates of certain values got the vote. [/ref]

- Women were entitled to vote in a university constituency if they had reached the age of 30 and would have been entitled to if they were a man.[ref] University constituencies were not geographical constituencies, but constitutional oddities which allowed graduates of a university to elect an MP to represent their interests. They were abolished at the 1950 General Election.[/ref]

- Women were entitled to vote in local government elections if they would have been if they were a man. However, this was not the case if their husband could also vote in local government elections with respect to a property they shared.[ref]‘Representation of the People Bill’, Cabinet Memorandum by W H Long, Colonial Secretary, 05/05/1917. Catalogue reference: CAB 24/12/55 [/ref]

These were the government’s proposals for partial women’s suffrage. They were an exercise in the politics of the possible as far as the government were concerned. The Speaker’s Conference on Electoral Reform on 1916-17 had brought together MPs and peers with a range of views on women’s suffrage, to try and draft a Bill which Parliament would accept on all sides. Measures such as prohibiting women from voting until the age of 30 (men voted at 21) were an attempt to make the Bill palatable to those the Home Secretary described as having ‘strong views’.

The Home Office ‘Long Papers’ on the Bill in the record series HO 326 provide a thorough timeline of the Bill’s passage through Parliament and the government’s coordination of this, and shows both the Bill’s acceptability to Parliament and the government’s reticence about any measures to expand female suffrage.

While amendments removing the women’s vote altogether in both the Commons and the Lords were comfortably defeated, another amendment showed up the government’s commitment to the Bill’s particular form of compromise. An anti-suffrage MP amended the Bill to give women votes at 21, almost certainly to try and sow division. The government urged MPs not to make the Bill unpalatable (one member warned that such a measure would give ‘servant-maids [and] daughters’ the vote) and said they would not take further responsibility for the Bill if it were changed.[ref] Catalogue reference HO 326/21 [/ref]

An amendment to the Representation of the People Bill which would have extended votes to women aged 21 and above. Catalogue reference: HO 326/21

A change in attitude

However, despite occasional timidity in the face of truly universal suffrage, the government’s promotion of the Bill marked a departure in its attitude to women’s suffrage.

For years the government had rejected the entreaties of suffrage campaigners both militant and peaceful. These brave women had reshaped much public and political opinion in favour of their cause by tirelessly delivering the message that women were entitled to the vote, as they contributed greatly in all aspects of British public life.

Furthermore, the First World War – still raging as the Bill was debated – and women’s contribution to it, had perhaps focused the minds of politicians and the necessity of supporting women’s right for the vote. Liberal MP Bertrand Watson summed this up eloquently in Parliament, particularly praising suffragettes who had ‘stood down’ during the conflict, aiding the war effort of a state that they had previously taken a ‘more turbulent attitude’ towards. However, votes, he said, should not be seen as a ‘reward’ for this conduct, but instead recognised as women’s ‘right’.[ref] Hansard, House of Commons Debates, 22.05.1917, Volume 93, columns 2164-2165[/ref]

Important changes

While the Bill passed through the house relatively unscathed by anti-suffrage politicians, eagle-eyed readers might notice that schedule 4 of the draft Bill presented to Cabinet (pictured above) differs slightly from the text of the Act itself. The changes reflect two quite significant victories for suffrage campaigners.

The first concerns university constituencies. Originally only women university graduates were entitled to vote. However, some universities had not awarded women degrees, even though they had studied for one. The final Act resolves this educational inequality, providing a vote for a degree-holder or someone who had carried out equivalent study.

The other change is perhaps more significant. The original Bill only provided married women local government votes as long as their husband was not entitled to vote with regards to the same property. Married women were therefore effectively disenfranchised from local elections.

This was, again, the government taking the Speaker’s Conference as a blueprint for what was politically possible. There was a fear that anti-suffrage politicians would not support a scheme to enfranchise so many wives locally as well as nationally.

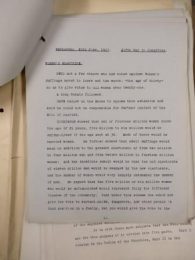

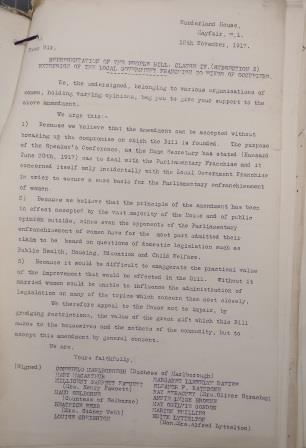

A letter from campaigners calling for the franchise in local elections to be extended to married women, November 1917. Catalogue reference: HO 326/21

But suffrage campaigners fought for this inequality to be removed. In November 1917, prominent suffrage campaigners – including Mary MacArthur, Millicent Fawcett and Beatrice Webb – wrote to the Home Secretary calling for married women to get the local vote. Local authorities, they pointed out, were often in charge of ‘Public Health, Housing, Education and Child Welfare … topics which concern [married women] most closely’. With this in mind, they asked for Parliament ‘not to impair, by grudging restrictions, the value of the great gift which this Bill makes to the housewives and mothers of the community’.[ref] Catalogue reference HO 326/21 [/ref]

Such petitions to sense were successful. The final text of the Act’s schedule 4(3) entitles a woman to vote in local elections not only if she would be entitled to if she was a man, but also if her husband is entitled to as well.

And so, after decades of tireless campaigning by many inspirational women, and months of parliamentary wrangling, the Representation of the People Act passed into law 100 years ago today. Over 5 million women were enfranchised.

Universal adult suffrage for both women and men was not realised until 1928 when women got the vote at 21 and property qualifications were done away with. But it is still a significant day in the history of democracy, and one worthy of celebration.

You would think by what has been said of today that only women got a (partial) vote, but according to TNA’s own article:-

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/citizenship/struggle_democracy/getting_vote.htm

that 6 out of 7 men before 1918 didn’t get the vote and in the case of for example a father and two sons over the age of 21 then only one of them could vote. Of course many men died as a result of the First World War when they went or were conscripted to go to war before they got the vote and they didn’t go around, for example, blowing up the Tea Room in Kew Gardens to smitherings. It does seem that there is some political correctness here. Of course you had to be British to vote so if you were a foreigner and hadn’t been naturalised then you couldn’t vote. The issue of voting still goes in, but in Scotland they allow 16 and 17 year olds to vote in the Scottish Referendum and Wales are considering but you can het married but you can’t vote under the age of 18 ( a suggestion that David Sutch (of the Monster Raving Looney Party) but at the time in charge of the Teenage Party.

Why did women stop campaigning for the vote in 1918 when only some women got the vote?

Only 10% of people owned houses then which is why so few women got the vote.

Was it because middle class women got the vote and the suffrage movement was largely middle class?

440 MP’s voted for or against the act. Were there 650 MP’s at this time and if so where can details of the abstained etc be found.

Hi Kenny,

Thanks for your comment.

We can’t answer research requests on the blog, but if you go to our ‘contact us’ page at http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact/ you’ll see how to get in touch with our record experts via phone, email or live chat.

Best regards,

Liz.

[…] the People Act 1918: Votes for (some) women, finally’, The National Archives (6 February 2018), http://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/representation-people-act-1918-votes-women-finally/ [accessed 18 April […]