Friday 18 May 2018, 18:30

Friday 18 May 2018, 18:30

Suffrage 100 – Archives at night: Law breakers, law makers

In March 1912, unprecedented window smashing campaigns took place across London’s West End.

On 1 March it was said that approximately 150 women smashed windows simultaneously across the capital – and this was only day one of the campaign. The scale and organisation behind such actions was unparalleled. The likes of such protests had never been seen before, and they were led by women.

Deeds not words

The Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), formed in 1903 by Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughters, took a militant stance on campaigning for votes for women, using the motto ‘Deeds not Words’. Often called the ‘suffragettes’, the WSPU had become frustrated that years of lobbying by other non-militant societies had not achieved the aim of women receiving the right to vote in parliamentary elections.

The WSPU’s policy of direct action had begun in 1905 when members, including Christabel Pankhurst, interrupted a meeting to ask politicians whether they were in favour of votes for women. However, it wasn’t until the events of Black Friday on 18 November 1910 that sustained campaigns of property destruction began. On that day, Emmeline Pankhurst led a deputation of around 300 women to Parliament: this resulted in long and violent clashes with the police. After the event, the WSPU submitted the testimonies of women caught up in the violence to a Parliamentary Committee, detailing accusations of police violence and sexual assault.

COPY1-551 Believed to be suffragette Mrs Ernestine Mills, and Dr Herbert Mills in top hat, Black Friday demonstration, 18 November 1910

Black Friday altered the WSPU’s campaigning. Over the next two years, the WSPU organised – among other acts – two large-scale window smashing campaigns. The first campaign took place in November 1911 and the second in March 1912.

Window smashing campaigns were used as a political statement. The suffragettes sought to prove that the government cared more about broken windows than a woman’s life. ‘The argument of the broken pane of glass’, Mrs Pankhurst told members of the WSPU, ‘is the most valuable argument in modern politics.’ If property was the government’s responsibility then property was a target.

Great Militant Protest

Records seized as evidence show the imtvitation sent out by Mrs E Pankhurst to take part in the March 1912 protests:

‘MEN AND WOMEN I INVITE YOU TO COME TO PARLIAMENT SQUARE ON MONDAY, MARCH 4TH 1912 at 8 o’clock to take part in a GREAT PROTEST MEETING against the government’s refusal to include women in their reform Bill. SPEECHES will be delivered by well-known Suffragettes, who want to enlist your sympathy and help in the great battle they are fighting for human liberty.’

This vaguely-titled ‘Great Militant Protest’ was a ‘skilfully planned secret attack’ that would involve over 150 women armed with hammers, stones and clubs simultaneously smashing the windows of shops and offices in London’s West End.

In response to her call to action , Emmeline Pankhurst received numerous letters of reply from women up and down the country, willing or unwilling to take part. Many of these letters, seized by the police in later raids on the WSPU headquarters, highlight the various pressures ordinary women faced in getting involved in militancy.

- DPP1-23 Ex142 Letter from Amy Woodburn to Mrs Pankhurst 26 February 1912

- DPP1-23 Ex147 Letter from Lady Constance Lytton regarding schoolteacher 19 February 1912

- DPP1-23 Ex153 Copy of letter from Nurse Ellen Pitfield 1912

Mrs Hetherington, for example, states that she cannot join the protest ‘as [she has] two little children, one only a few months old’. Another, on behalf of Mrs Avery, suggests that because she is a school teacher ‘her imprisonment would mean the sacrifice of her economic independence’. The struggle between family pressures and commitment to the cause is particularly evident in the poignant letter from suffrage supporter, Francesca. Although, as she points out, she loves the cause better than her life, her fear of defying her mother prevents her from joining. She exclaims, ‘The only gift I envy anyone is freedom and I am hoping someday to get mine.’

Despite the risk, hundreds of women from across the country signed up to take part. This included Nurse Ellen Pitfield who, in her reply to Emmeline Pankhurst, states:

‘I am with you heart and soul in the great demonstration… A soldier to the death’

‘Better broken windows than broken promises’

On the day of the raids, the police were prepared for the attack. Plain-clothed Special Branch police officers were positioned outside the Gardenia restaurant, ready to pursue anyone who came out. Detective Edmund Buckley describes keeping a close watch on the restaurant from 17:00.

‘Between that time and 6:30 a number of women went in, in twos and threes– they went upstairs to the second floor. From about half past 6 to about quarter past 7 I saw various small parties of women leaving.’

Edmund decided to follow two women – identified as Alice Angus Wilson and Morrie Hughes – down to Whitehall, where he saw Wilson ‘take her hand out of her muff and throw a stone at the ground floor window’. She was immediately arrested by another officer.

On their stones or hammers were often phrases: Lillian Ball’s hammer had the words ‘Better broken windows than broken promises’.

In another statement, Detective Ernest Bowen describes seeing three women come out of the restaurant and walk towards Charing Cross tube station, followed by a crowd of about 20 people and some uniformed policemen. After getting a tube to King’s Road they proceeded to walk down it until they got to the post office: ‘All 3 suddenly ran to the window and smashed it’.

The impact of these campaigns

- Summary of claims, damage by Suffragettes, March 1912. Catalogue reference MEPO3-1787

- One example page of insurance claims, for damage by Suffragettes, 1912. MEPO3-1787 (6)

Over 126 women were committed for trial following the window smashing campaign. For many it was their first offence. The sentences at the trial ranged from 14 days to six months; 76 women were given sentences of hard labour. The harsh sentences meted out to working class suffragettes did not escape the attention of the accused or their supporters.

A Metropolitan police document survives recording a summary of claims from March 1912. The list of claims for damage caused by suffragettes includes the name of each claimant and the address, damage done, amount claimed and, occasionally, extra comments. This list of buildings is a powerful testimony to the impact these campaigns had on private property across the capital. The claims highlighted broken windows, as well as damage to electric lighting systems and loss of trade. Many of the streets and addresses are still recognisable, such as Oxford Street, Regents Street and Harrods.

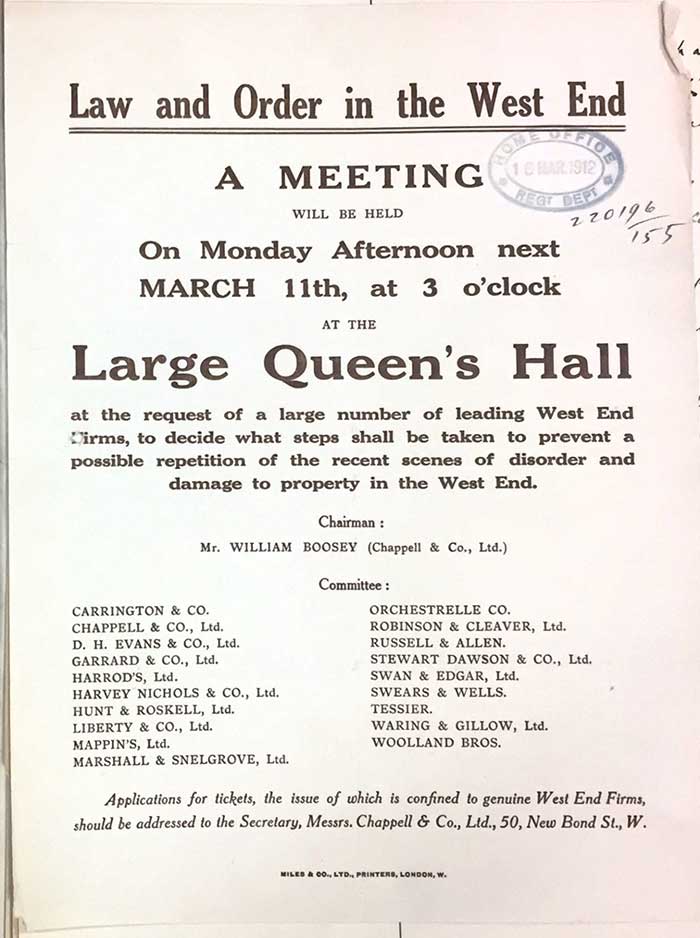

By 11 March a gathering was instigated of the leading West End firms, to try and counter this threat, including attendance from Liberty’s and Harvey Nichols.

Resolution after 1912 window smashing campaign by prominent buisnesses. Catalogue reference HO 144_1193_220196

One of the things most powerfully conveyed by these raids is how organised the movement was: these were campaigns never been seen before or since.

These campaigns were not instantly successful, and militant methods continued to escalate until the suffrage amnesty at the outbreak of the First World War. However, the role of militant methods continues to be debated to this day. Did it help or hinder women’s fight for the vote?

Welcome to Suffragette City

‘Suffragette City’ is an immersive experience taking place at the London Pavilion in Piccadilly.

The historical landscape of these window smashing campaigns is the reason why our Suffragette City project is proudly situated in the West End – in Piccadilly Circus, which was at the heart of these acts of property destruction with a political cause.

One of the most powerful individual testimonies relating to the window smashing campaigns comes from Lillian Ball, a working class dress maker from Tooting. Suffragette City allows you to follow her personal struggles in getting involved in this movement, as told through the surviving archive material.

Join us to walk in her footsteps, and ask yourself the difficult questions that Lillian had to face.

Suffragette City runs at the London Pavilion, Piccadilly Circus, from 8 to 25 March. If you’re interested in visiting, you can book tickets online.

This article is a real help to me in writing my book. I haven’t found anything that detailed the window smashing campaign as completely. Nice work.

The Times described the event as ‘an unprecedented campaign of wanton destruction.’ Among the 121 women caught was Mrs Pankhurst, ‘the notorious agitator,’ who, whilst being arrested for lobbing a stone through a window of 10 Downing Street, wriggled free and threw another, wrecking a window of the Colonial Office. She was sentenced to two months’ imprisonment. The smashing raid recommenced on 4th March and focused on the plate-glass windows of West End shops. ‘Suddenly women who had a moment before appeared to be on peaceful shopping expeditions… began an attack upon the nearest windows.’ ‘From every part of the street came the crash of splintered glass.’ Some 6,000 police were detailed to catch them, assisted by shop workers and the public, yet most women managed to smash about ten windows before being stopped. Fifty women were arrested. Under the banner headline ‘WOMEN TERRORISTS OF LONDON’ the Daily Mirror ran a long article, which included this remark: ‘One elderly woman, who was cosily dressed in furs, was very inexpert at the new occupation.’

Did any women participate in protests of W W I? If so, where?

I possess the stone that Alice Agnes Wilson threw through my grandfather’s office window in Whitehall ( he worked for the ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries). Reports of this campaign are in his diary along with a newspaper cutting of Alice getting 3 months hard labour. He describes how colleagues were standing outside when an older and young women approached. The older woman’s stone missed but the younger one’s smashed the window. He says “I have one of the stones!” From its geology, it was picked up from Brighton beach. We reckon Alice and/or other ladies went there to fill bags for this campaign.

How fascinating! Thank you for sharing this story with us. It’s so interesting to see the other side of these interactions and that your grandfather saw this as an important moment to record in his diary.