The headquarters of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), the militant strand of the women’s suffrage movement, were constantly vulnerable to police raids.

As militancy in the movement escalated, the methods used by the police and government to counter it became more dramatic and creative. These raids leave a great legacy of information about this women’s movement: how they organised, communicated, and orchestrated militant campaigns.

Clement’s Inn

Women’s Social and Political Union message codes, seized as evidence against Emmeline Pankhurst in 1913. Reference: DPP 1/23.

The WSPU was famously formed in Manchester by the Pankhursts; however, their influence spread quickly and the WSPU soon had offices all over the country to run their regional campaigns. Their ambitions meant they needed a London headquarters to centralise control of the movement and administer their national operations. To support this growing movement, the Pankhurst’s early associates, Emmeline and Fredrick Pethick-Lawerence, helped the Union acquire 4 Clement’s Inn on the Strand in London: from 1906 this building acted as their general offices.

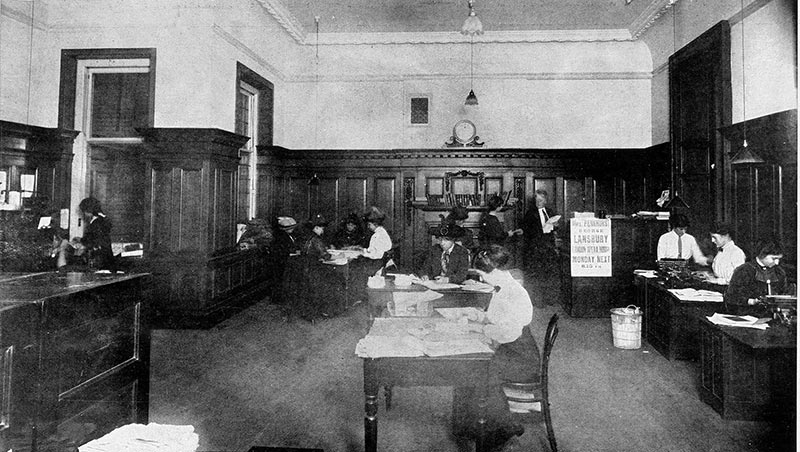

Photos and autobiographies from the era bring to life the headquarters, illustrating a lively and active movement. Portraits of key figureheads in the organisation adorned the walls and typists filled the offices, which boasted modern conveniences such as electricity and telephones (albeit monitored by the police). In the excitement of the atmosphere, many people were said to have converted to the movement on their first visit to Clement’s Inn.

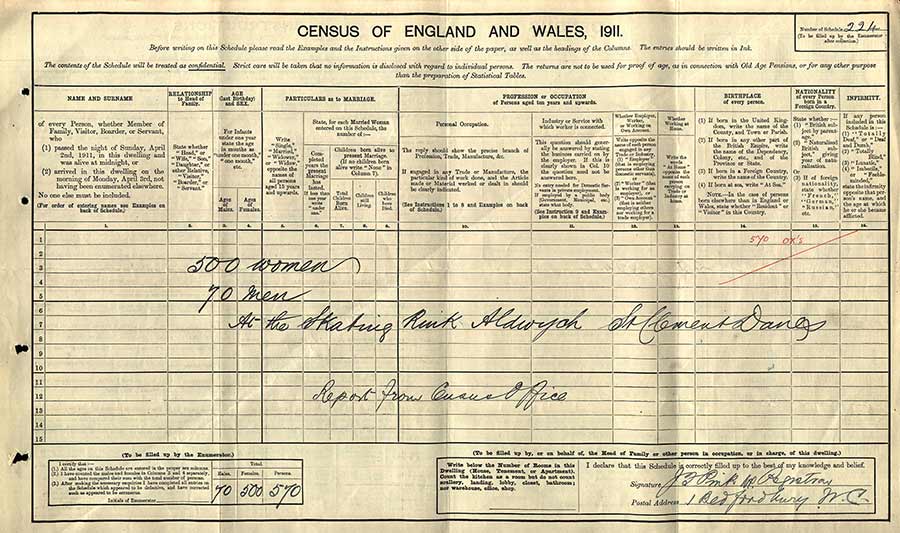

Census boycott at Aldwych Skating Rink noting approximately 500 women and 70 men boycotting the 1911 census. Census Returns of England and Wales, 1911. Reference: RG 14/1194

The location was ideal for lobbying Parliament and politicians. It was also local to the Aldwych Skating Rink, which many members visited for the mass census boycotts in 1911.

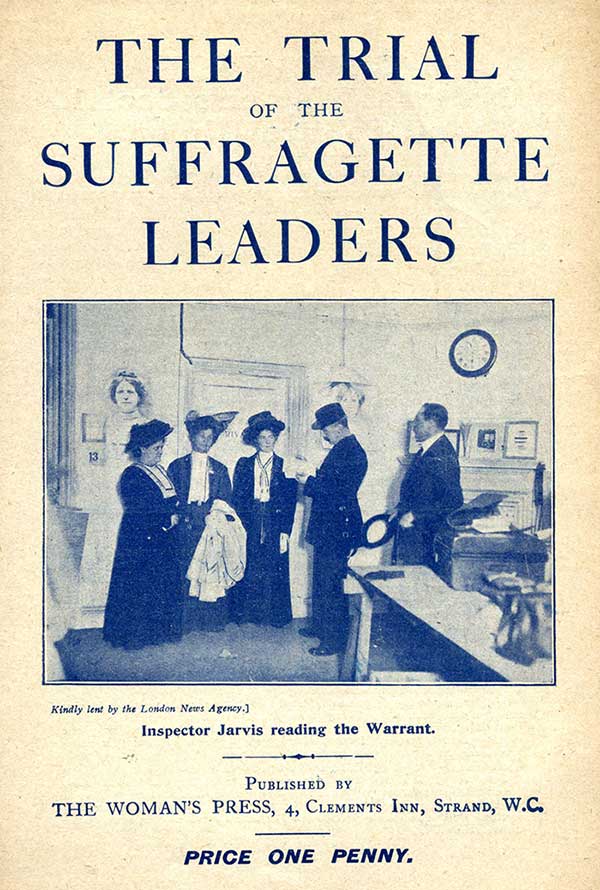

Cover of ‘The Trial of the Suffragette Leaders’ showing the arrest of Emmeline Pankhurst, Christabel Pankhurst and Flora Drummond, 1908. Reference: PRO 30/69/1834.

When, in 1908, Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst were arrested at Clement’s Inn in connection with a ‘rush’ on the House of Commons, they hid on the roof terrace while police searched the building. The suffragettes then descended in their own time to meet the police and a photographer they had organised. The result was a striking photograph of their arrest, showing these women’s remarkable ability to seize every propaganda opportunity.

Lincoln’s Inn House

By 1912 the organisation’s aspirations had outgrown Clement’s Inn, and they acquired new premises around the corner at Lincoln’s Inn House. This physical movement also marked a break within the WSPU. The previous premises had been associated with the Pethick-Lawrences; however, this couple had been disowned by the movement they had long worked for and funded, when they criticised the WSPU’s increasingly militant methods.

The offices of the WSPU are a perfect illustration of just how organised the movement was; it was from these headquarters that their national militant campaign was fought.

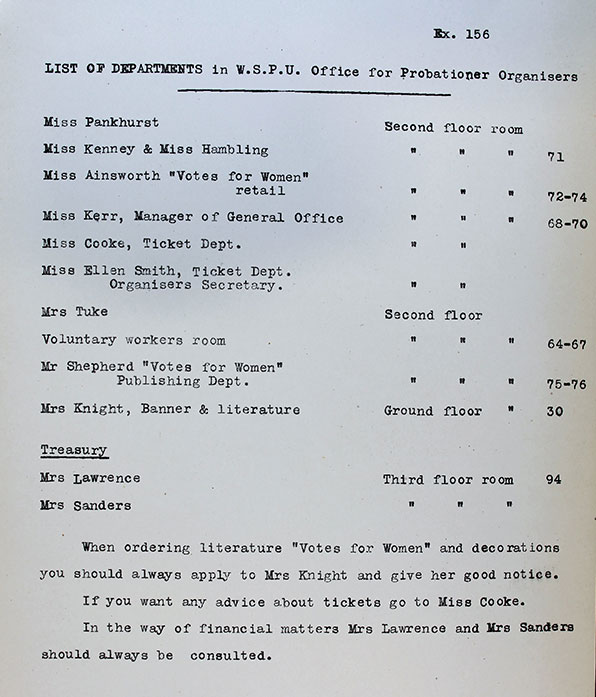

Exhibit 156, listing departments in the WSPU headquarters. Reference: DPP 1/23

Over five floors this new London headquarters had space for the variety of departments now needed, including a banner secretary, ticket secretary and even a press department. The offices show that, despite the public militant campaigns, more traditional political meetings, administration and propaganda underpinned the organisation. The building was dominated by the general office, led by Miss Kerr – an efficient and organised business woman, who kept things running smoothly. Most notably, there was now a prisoner’s secretary, reflecting the vast number of women – and indeed men – going to prison for the cause.

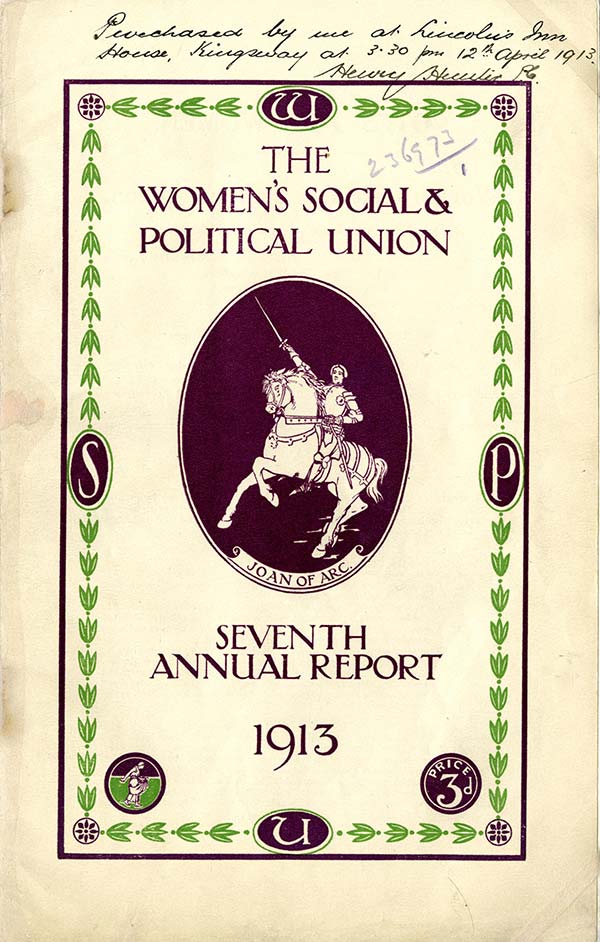

The headquarters hosted many key activities, which were documented through copies of ‘The Suffragette’, from Christmas bazaars to preparations for self-denial week. The front of the building housed a sale room, which sold various types of suffrage literature, packets of tea and playing cards. During their investigations, police would buy items from the shop. A copy of the Seventh Annual report of the WSPU in the collection of The National Archives is annotated, showing it was purchased by a police officer at Lincoln’s Inn House, at 15:30 on 12 April 1913.

A copy of the Seventh Annual report of the WSPU, annotated that it was purchased by a police officer at Lincoln’s Inn House, at 15:30 on 12 April 1913. Reference: HO 45/10700/236973.

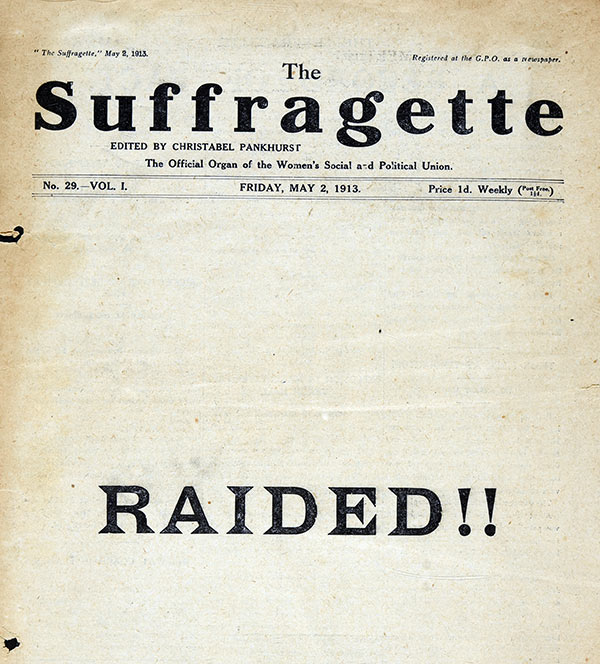

‘Raided!!’

Frustration continued in the movement at the lack of progress by government on conciliation bills. In retaliation, suffragettes waged unprecedented arson campaigns on both public and private property. The government turned to targeting WSPU buildings in an attempt to gather the vital evidence they needed to prosecute its leaders. The new government approach was to target key figures on more significant grounds, such as ‘conspiracy’, leading to longer imprisonment. This strategy generally failed, with constant releases due to hunger strikes.

Front cover of ‘The Suffragette’ from Friday 2 May 1913, after a raid on Lincolns Inn House. Reference: ASSI 52/212.

On 30 April 1913, a major raid took place on Lincoln’s Inn House. At 11:00 uniformed and plain clothed police officers were said to have ‘swarmed’ over the building, swiftly blocking all exits. By 13:00 the offices at Lincoln’s Inn were closed and under police control. An anonymous report in ‘The Suffragette’ noted: ‘The constables must have been surprised at the cheery and amused looks with which they were greeted.’ The chief organisers present in the building were arrested, including the editorial team, consisting of Miss Lennox, Miss Lake and Miss Barrett, alongside Harriet Kerr and Miss Saunders, the finance officer. All of the women were charged with conspiracy to do wilful damage.

At the same time, the current printers of ‘The Suffragette’ were raided, removing the copy that had been written for the majority of the publication.

As a result of this, the May 1913 edition of The Suffragette looked like no other edition. Instead, the official organ of the WSPU bore this stark headline – ‘RAIDED!!’ – against the scant plain background. In a classic act of defiance they had managed to still print their paper, rewriting what they could of the copy that had been seized.

The general office at the WSPU headquarters, Lincoln’s Inn House, Kingsway. As seen in the Illustrated London News. Reference: ZPER 34/142.

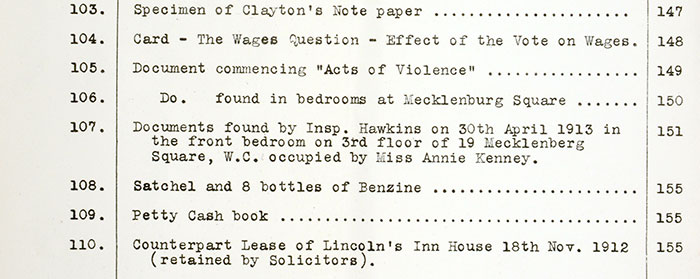

Although raids continued on Lincoln’s Inn House after this point, in this raid in particular a wealth of evidence was gathered. It was noted that removal vans took vast amounts of material from the building. Items seized create a picture of the extent of the networks and organisation behind the militant campaigns. They provided the police with evidence of the arson and bombing campaigns being coordinated through the headquarters. Hammers were found inscribed with ‘WSPU’ on the handles, leaflets which were thought to incite violence were seized and, in Annie Kenney’s room at Lincoln’s Inn, the police found a satchel containing eight bottles of benzine, a highly flammable liquid.

List of just some of the evidence collated for the Director of Public Prosecutions in relation to the Conspiracy Trails. Reference: DPP 1/19.

In the following month, key figures in the movement would largely be found in court. Paradoxically, this gave these suffragettes another platform through which to make their voices heard.

The legacy of many items seized in these raids can be seen in our current exhibition Suffragettes vs. the State. State surveillance of these spaces means we have an unprecedented insight into the heart of the militant suffrage campaigns.

Visit our exhibition to experience more of this extraordinary material.

Of course their offices should have been raided on numerous times by the police, that is what the public who have expected, they were after all involved in the planning of arson and bombing (which may have ended up with deaths of innocent people), what you have described is what today we would call a ‘terrorist cell’ and we should really stop calling it militancy and call it for what it was (terrorism) and to praise the women and men for this is wrong. I do wonder why file DPP 1/23 mentioned above was closed for 75 years. The Government in my view should have more strict with the ‘militant’ wing of the Suffragettes, in earlier times they would have been transported to Australia, though I don’t see why they should have had the problem to deal with. These women and men were no “Joan of Arc” characters.

When one’s rights are being suppressed, and traditional legal avenues are bearing no fruit, a level of militancy is inevitable. A terrorist may be a freedom fighter by another name. ‘Twas ever thus.