In the run-up to Christmas of 1932, two plain clothes police officers were welcomed into a drag party at 27 Holland Park Avenue, London. Introduced to their fellow party-goers as ‘camp boys,’ and posing as boyfriends, they chatted, kissed, and danced the night away.

Hospitality would not run short. Yet these same police officers would later return to arrest their new acquaintances – men sporting ‘ladies’ evening clothes,’ who were introduced as ‘Queenies’; men sporting lounge suits, who were introduced as ‘Kings’ – on grounds of ‘divers lewd, scandalous, bawdy and obscene performances and practices.’

The official accounts given by these two police officers, PC Labbett and PC Chopping, are held at The National Archives (CRIM 1/639). And at the Queer and the State workshop, hosted by The National Archives in collaboration with the London Metropolitan Archives on Saturday 19 November 2016, I was invited to share my reflections on these captivating accounts of queer, criminalised life in 1930s London.

The extent to which PC Labbett and PC Chopping were prepared to implicate themselves intimately in the events of the evening is striking. They might have dedicated themselves to observing what other men were doing at the party, resolved to maintain something of a professional distance. Yet their accounts suggest that they were charming and warm, and that they kept close body contact with their new companions.

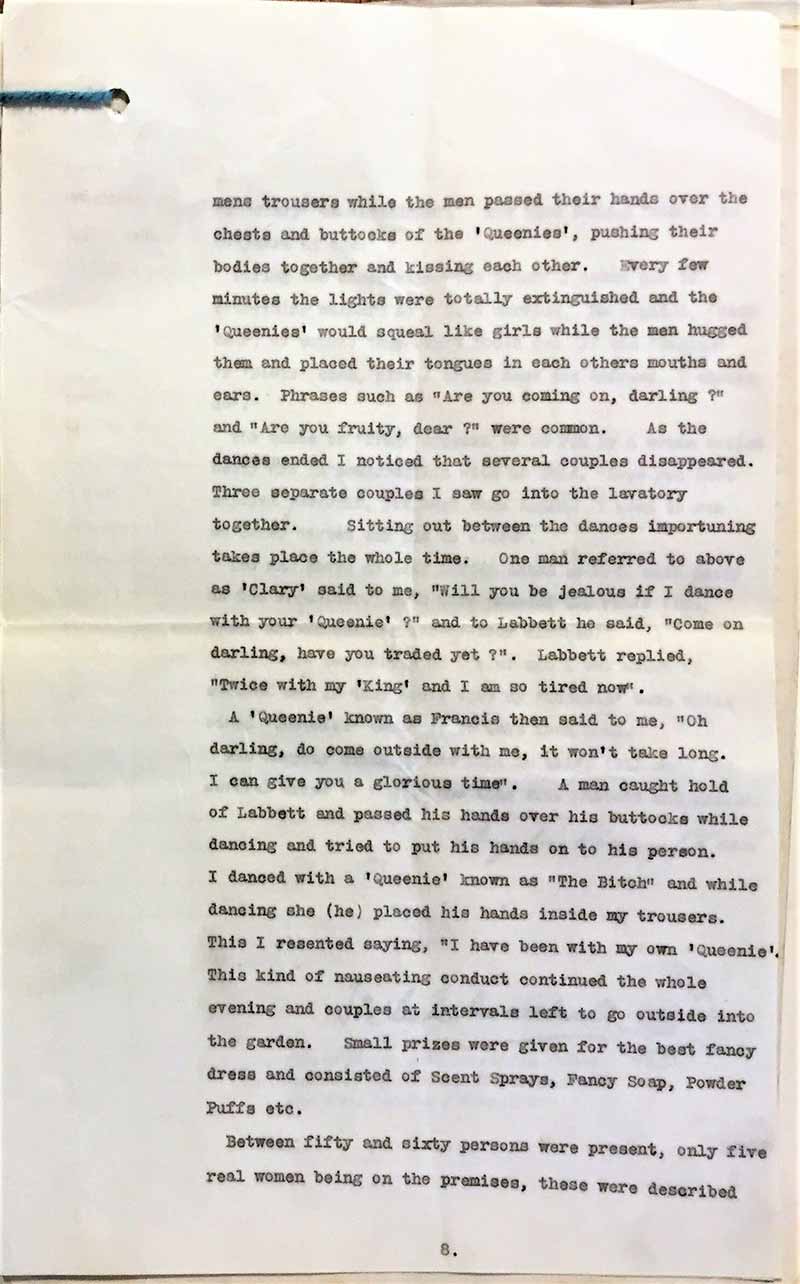

By their accounts, they share dances, they have conversations about possible sexual contact, and they let themselves be kissed and touched intimately. They engage in role-play more elaborately than they might. When PC Labbett is asked by one attendee whether he has ‘traded’ tonight (and the term ‘trade’ here can be used to describe sexual contact between men, with or without payment), PC Labbett replies,’Twice with my boy friend,’ and indicates PC Chopping. Interestingly, by PC Chopping’s account, PC Labbett makes use of the argot of the party: ‘Twice with my “King,”‘ he replies, ‘and I am so tired now’ (CRIM 1/639).

Extract from the account of Police Constable Henry Eric Chopping (catalogue reference: CRIM 1/639)

And so the role play here seems excessive. It moves beyond the necessities of work, beyond the basic need to acquire evidence, into the arena of play. It is stimulating, then, to consider how these police officers were complicit in the pleasurable queerness of the evening’s events, rather than necessarily serving as counterpoints to the men who chose to attend the drag party. There is, at least, something of a queer space here for interpretation.

It’s interesting to note that the appearance of the police officers seemed to arouse no suspicion in their companions. In their accounts, PC Labbett and PC Chopping make efforts to describe the makeup and clothing worn by other attendees, as if to mark out their queerness and to distinguish these men from themselves. And yet, apparently without makeup or special clothing to identify them as kindred spirits, PC Labbett and PC Chopping were quickly granted access to 27 Holland Park Avenue. And so we might not find such a clear divide between the man who would participate in a drag party, and the man in the street.

While the use of agents provocateurs in contemporary cases of ‘homosexual offences’ was not uncommon, it was a cause for concern for legal professionals. Just a few months after these police officers infiltrated the drag party at 27 Holland Park Avenue, a magistrate tried another case relating to police entrapment at a public urinal in Bermondsey. Attacking the methods used by police officers in this case, he declared: ‘it is in my opinion a sacrifice a Police officer should not be required to make … to invite and endure an insult, to his manhood, of a gross character. His own self esteem must suffer and it effects [sic] the dignity of the Force. I sincerely hope it will end’ (MEPO 3/990).

For further details of the case launched against the drag party-goers at 27 Holland Park Avenue, including material evidence used in the case, see ‘Lady Austin’s camp boys‘ by Diverse Histories Records Specialist Vicky Iglikowski.

My thanks to Vicky Iglikowski and Rowena Hillel at The National Archives, and to Tom Furber at London Metropolitan Archives, for leading the Queer and the State events for the Being Human festival, and for inviting me to participate as a member of a student advisory panel.

Queer City: London Club Culture 1918-1967, a collaborative project between The National Archives and the National Trust, is now open at Freud Café-Bar, 198 Shaftesbury Avenue. For more information visit: www.nationaltrust.org.uk/queer-city-london

They were pardoned according to Discovery and the use of agents provaceteurs was officially frowned on from a case in 1928 (?the Bermondsey case) although it was suggested even in the 1980s (see the recently released Home Office files).