With the arrival of mustard gas in July 1917, the medical services faced a new challenge. This was not the first time that poisonous gas had been used on the Western Front, but this one settled in the soil and could continue to contaminate for weeks. It also caused long-lasting effects for those who were unfortunate enough to encounter it.

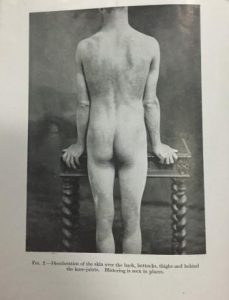

‘The vapours of dichlor-diethyl sulphide and mustard gas produce no immediate physiological or pathological changes, but after a few hours the skin becomes severely inflamed, and inflammation of the eyes and the mucous membrane of the air passage ensues. The parts of the skin which are most commonly and certainly most severely affected are the expose surfaces and those where there is increased perspiration: the skin over the genitals, between the buttocks, and the thighs are invariably involved.’ (WO 142/330)

Inflammation of the skin could be of varying degrees, from a discoloration to a severe destruction of all the skin tissue, which could leave marks resembling scalds. In typical cases of poisoning by these substances, severe conjunctivitis would also occur.

- Discolouration of the skin over the back, buttocks, thighs and behind the knees (catalogue reference: WO 142/330)

- Discolouration and blistering of the skin (catalogue reference: WO 142/330)

Another common symptom was copious expectoration – the coughing up and spitting out of mucus from the lungs. In severe cases bronchitis and broncho-pneumonia could occur; in more severe cases, scar tissue could also build up in the lungs. It was stated that x-rays should be taken of those who reached this stage in order to properly assess damage. Headaches, pains in the stomach and vomiting were also symptoms of inhaling mustard gas.

As seen by the effects above, rapid treatment was required to neutralise this irritant. To deal with such casualties, forward decontamination units were established, to bring treatment closer to the front lines.

Not just at the Front

Case of a man who had worked in one of the factories producing chemicals/mustard gas (catalogue reference: MUN 4/6906)

It wasn’t just men on the front lines who were in harm’s way. MUN 4/6906 contains accounts of men who suffered from exposure to mustard gas through the production of it, experimentation with it, or through a piece of clothing which had been inadvertently exposed to the chemicals.

There is a story of one man who wore a tie which he had previously worn in the vicinity of an experiment concerning mustard gas. He wore the tie again a few days later and the skin under his chin started to become irritated. It soon became apparent that the chemicals had permeated the tie and were causing this irritation, even after a few days. Naturally, and fortunately, it wasn’t as severe as the effects experienced by people faced with a greater concentration of the gas, on the front lines.

Another case details a man who had to take months off work, after a workplace accident involving a leakage of liquid mustard gas. As a result, he suffered from a great deformity of his left hand and wrist – which was difficult to move – with severe problems relating to his third and little finger. As well as these injuries, he displayed some of the characteristic symptoms of gas exposure: skin discolouration, coughing, expectoration and problems with his breathing and lungs. He was sent to the Royal Orthopaedic Hospital in Great Portland Street, and was paid some allowance from the Government – although it did not amount to the equivalent of his full wages. Some argument about this ensues within the pages of the files dedicated to him.

Research at Porton Down

The biggest issue was how to protect men from this gas, or, if nothing else, treat the effects of exposure to it. Research was done into this, and experiments undertaken, throughout the country.

The biggest, and probably most well known (then and now), of the centres for this was at Porton Down. Early in 1916, the government took over the area of land which we now know as Porton Down, the government military science park. Initially referred to as W.D Experimental Ground, Porton, it became known as Porton Down in 1918. By that time, it had 6196 acres of land in which to undertake its important scientific work.

Much of the experimentation took place on animals, including goats, cats and monkeys; the site had a farm to breed and rear animals for this purpose. However, some experimentation was done with humans. A special hut was built in the main camp and fitted up as a laboratory and respirator store. Early experiments consisted of field trials on the penetration of respirators, and others tested if fitting dug-out entrances with blankets soaked in chemicals offered protection against gas. This latter course of experimentation was important: if dug-outs could be protected from gas they could be used to store food or treat immediate casualties.

The experiments undertaken on human skin usually consisted of mustard gas being put on a small patch of skin and studying its reaction with various other chemicals; this tested what form of protection other chemicals provided. This also allowed the chemists to trial different ointments, such as bleaching powder, Vaseline, paraffin and magnesium oxide. Salt baths were also tested on skin that had blistered to find out whether this was an effective remedy for easing the pain afterwards.

Porton Down’s work into chemical warfare continued after the First World War and is still ongoing today. Nowadays, it is the site of the Defence Science and Technology Laboratory; looking into chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear defence.

Our documents

Our PIN 26 collection has a few examples of men who suffered prolonged effects of mustard gas poisoning further on in their lives. If you search for gas in general, over 300 results come up, indicating how terrible a weapon the introduction of gas was. Likewise, PIN 82 contains a number of files for men who died as a result of gas, or from gas shells.

For further research into Porton Down and chemical warfare, WO 142 is rich with information.

What Nationsl records, if any, that pertain to the “The Valley Works”, are available. This site at Rhydymaawn, Flintshire was storage and a production site for “Runcol” a mustard gas made at Wigg Island, Runcorn, Cheshire.

Some records exist at the Flint records office, but I wonder what national records exist ?

We at the Rhydymwyn Valley History Society believe we have all of the TNA docs relating to the above sites and they are available to all of our members. Please google us.

My great uncle was part of early lung treatments related to Mustard gas exposure. These wre not expected to live long so they were give a choice to participate. He was one of the few that did recover well living to 102.

His claim was that some form of limited lung transplant had occurred. As tissue match and the like was not worked out well at that time, it may be to great luck that it worked. The modern question persists as to why it worked. Further denial that such procedures took place remains sad and untrue to this day.