This year marks the 70th anniversary of a military coup that occurred during the first year of the reign of Bhumibol Adulyadej, the late king of Thailand. The coup took place during the chaotic transitional period that followed the suspicious death of Bhumibol’s brother, King Ananda, and was an important event for Southeast Asia, and for Thailand in particular. In November 1947 the military seized power from the civil government and reinstated the military dictator Field Marshal Phibunsongkhram. This coincided with the onset of the Cold War and the establishment of a communist regime in Southeast Asia.

Much has been written about the Cold War in this region. However there are few mentions of the significance of the coup in Thai-American relations. It eventually led to the United States’ involvement in Southeast Asian political and economic development in order to limit or contain the spread of communism in Southeast Asia.

Following the post-war peace negotiations in 1946 and as a result of the contributions made to the Allied war efforts by the Free Thai Movement, the United States became Thailand’s protector. At first the United States saw Thailand as part of a regional plan to rebuild Japan’s economy, but the end of the Pacific War unfortunately did not bring peace to Asia.

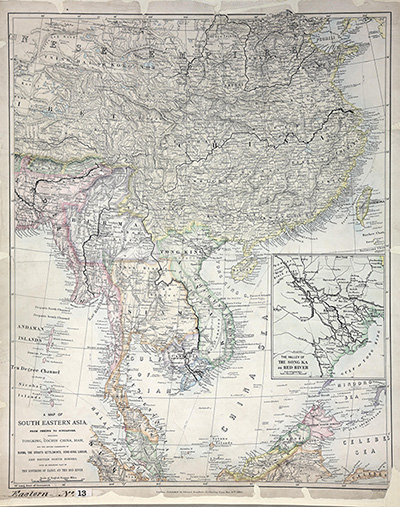

A map of Southeastern Asia from 1883 (catalogue reference CO 700/EASTERN13)

The return of Allied powers to Southeast Asia after the war led to anti-colonialism in Vietnam and Malaya in 1948; the civil war in China in 1949; and by 1950 the two Korean political systems were at war with each other. All these events caused the United States to reconsider Thailand as an ally to contain the spread of communism in Asia.

The Military Assistance Agreement

By 1950 a change in American attitudes to Southeast Asia in general and Thailand in particular became apparent, as the United States sought allies to contain the spread of communism. At the same time Phibunsongkhram’s foreign policies during his second administration were characterised by anti-communism, and therefore aligned towards American policy. Towards the end of 1949 the United States’ interest in the region ensured that Thailand would receive military assistance; and by 1950 Thailand was at the heart of the United States’ Far East policy and the principal recipient of their aid in Southeast Asia. Phibunsongkhram’s decision to align Thailand with the United States in 1950 was therefore the most significant aspect of Thai foreign policy, motivated jointly by a need for financial assistance and concerns about the proximity and growing influence of communist China.

Following the Southeast Asia aid program conference, which was held in Bangkok in March 1950, Thailand received $10 million in military aid. On seeing that his policy was beginning to succeed, Phibunsongkhram sought to further improve relations with the Americans and to complete his post-war foreign policy revolution.

The arrival of the Korean War

His opportunity came on 24 June 1950, when the United Nations Security Council condemned North Korean aggression. Three days later all U.N. members were called upon to stop the invasion, and on 29 June the U.N. cabled the Thai foreign ministry to request material aid. Phibunsongkhram offered 4,000 men – the first sent by any Asian country – and subsequently agreed to supply 40,000 tons of rice.

In mid-October 1950 the United States and Thailand signed an agreement that brought Thailand into the Military Assistance Program (MAP) and resulted in a permanent Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAGG) being stationed in Thailand. Between 1951 and 1953 military aid to Thailand increased from $10 million to about $56 million.

By 10 November 1950, the first battalion of the 21st regiment of the Royal Thai Army, which had been established that September at the request of the United Nations, disembarked at Busan Port; between 31 October and 11 November 1953 they took part on the Battle of Pork Chop Hill. At around the same time two Thai warships, HTMS Prasae and HTMS Bangpakong, arrived in South Korea. They served under United Nations command, performing escort duty and shelling enemy targets on land.

Covert Operations in Indo-China

In order to counter Chinese communist advances in Korea the United States military contemplated arming Chinese nationalist insurgents in Burma for an invasion of southern China. Meanwhile they began supplying arms to scattered anti-communist forces: between 1500 and 2000 Kuomintang troops remained in Yunnan province and the Shan states of northern Burma. The Thai government provided covert assistance, as Phibunsongkhram admitted in conversation with British ambassador Sir Geoffrey Arnold Wallinger. Thailand certainly benefitted from its participation; between 1950 and 1975, $650 million in military aid was received, and nearly 75 percent of it went towards counter-insurgency activities.

Between 1953 and 1954 former OSS Chief William Donovan was appointed ambassador to Thailand by President Eisenhower to oversee the development of counter-insurgency. After taking up his post, Donovan appointed former OSS agents who had seen service in Thailand during the Second World War to train the Thai police in guerrilla warfare at secret bases in northern Thailand. Donovan also helped the Thai military government establish an intelligence agency (krom pramuan ratchakan phaen-din) to gather information on national interests and security from both secret and open sources.

The US inherited the role of protector of South Vietnam in 1954, following the decisive Viet Minh victory over France at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu. With French colonial rule at an end, Donovan was instrumental in drawing Thailand into a multilateral defence pact that allowed the Americans access to air bases in the Thai northeast. In the same year Thailand signed the Southeast Asian Collective Defence Treaty, which gave life to the Southeast Asian Treaty Organization or SEATO. This created a common front with other allies in the region and established provision for multilateral military forces, while avoiding a direct and unilateral US commitment. Bangkok was chosen as the headquarters for the new organization, and as American military and economic aid continued to increase, so did clandestine activities above and beyond the auspices of SEATO.

The coup of 1947 was therefore an important event for Thailand and for Southeast Asia as a whole, as it greatly increased the United States’ involvement in the political and economic development of Southeast Asia as part of their effort to limit the spread of communism.

Further reading

Fineman, D. ‘A Special Relationship: The United States and Military Government in Thailand, 1947-1958’

Kislenko, Arne. ‘A Not So Silent Partner: Thailand’s Role in Covert Operations, Counter-Insurgency, and the Wars in Indochina’ Journal of Conflict Studies [Online], Volume 24 Number 1 (1 June 2004)

SEATO actually stands for Southeast Asia (rather than Asian) Treaty Organization. I would argue that anti-Colonialism is really freedom to run your own country and steps from the empires of west European countries, including The Netherlands and Portugal. We should not forget that Siam (Thailand) and Malaya were important for rubber supplies so there was a case of self-interest in preserving the status quo.