This year sees the 100th anniversary of the battle of Passchendaele. It was one of the bloodiest campaigns of the First World War and will be forever associated with the appalling conditions created by the continuous rain and mud of the battlegrounds. Men died needlessly for little military gain.

Back home in Britain, people were often ignorant, or complacent, about the truth of what the men were suffering in the trenches. The agonies suffered by the men at Passchendaele were very different from the myth of glorious sacrifice propagated at home. The war poet Siegfried Sassoon had seen and experienced the horrors of the trenches and was determined to convey the grim reality through his poetry.

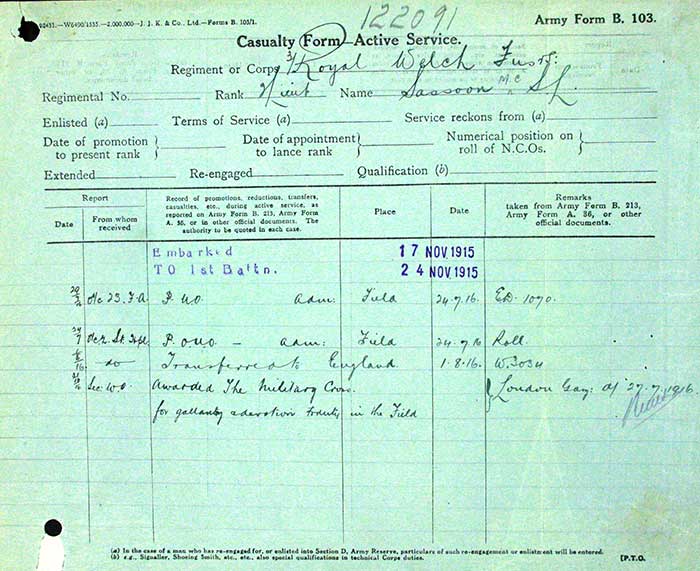

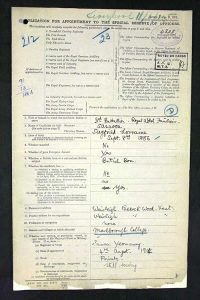

Sassoon first enlisted with the Sussex Yeomanry in 1914, and was commissioned into the Third Battalion of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers as a Second Lieutenant in 1915.

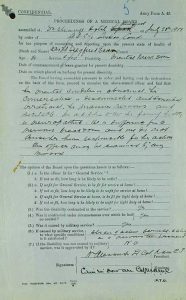

- First page of Sassoon’s application for a commission in the 3rd Battalion of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers

- Confirmation of Sassoon’s appointment

In November 1915, Sassoon was posted to the First Battalion of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers and sent to the Western Front.

Casualty form recording Sassoon’s embarkation for France and posting to 1st Battalion of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers

He gained a reputation for reckless bravery and became something of a war hero, winning the Military Cross in July 1916. The citation records that he ‘remained for 1 ½ hours under rifle and bomb fire collecting and bringing in our wounded’ (Supplement to London Gazette 27 July 1916, p 7441).

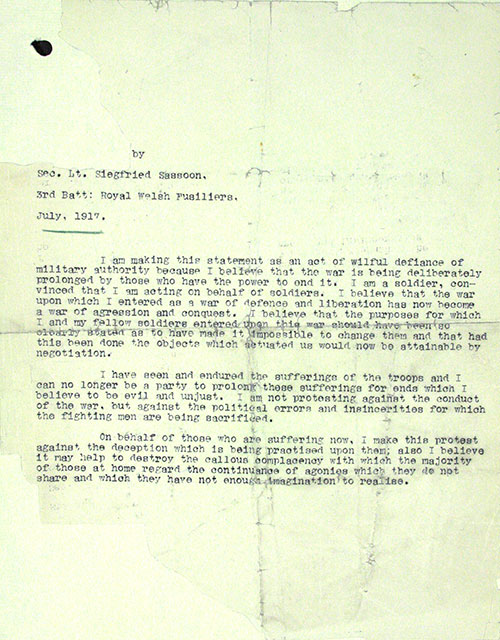

In April 1917, Sassoon was wounded in the shoulder and repatriated. By July he had recovered and, after a spell of convalescent leave, was declared fit for general duties. His experiences in the trenches had shown him the full horror of the war, leading him to question its validity. In an open letter to his commanding officer he declined to return to duty. This letter, entitled ‘Finished with War: A soldier’s declaration’ was forwarded to the press and read out in Parliament.

In it he states:

‘I believe that the war upon which I entered as a war of defence and liberation has now become a war of aggression and conquest… I have seen and endured the sufferings of the troops and I can no longer be a party to prolong these sufferings for ends which I believe to be evil and unjust. I am not protesting against the conduct of the war, but against the political errors and insincerities for which the fighting men are being sacrificed.’

Through his poetry, Sassoon wished ‘to destroy the callous complacency with which the majority of those at home regard the continuance of agonies which they do not share, and which they have not sufficient imagination to realise.’

Copy of ‘Finished with War: A soldier’s declaration’ found left on a train

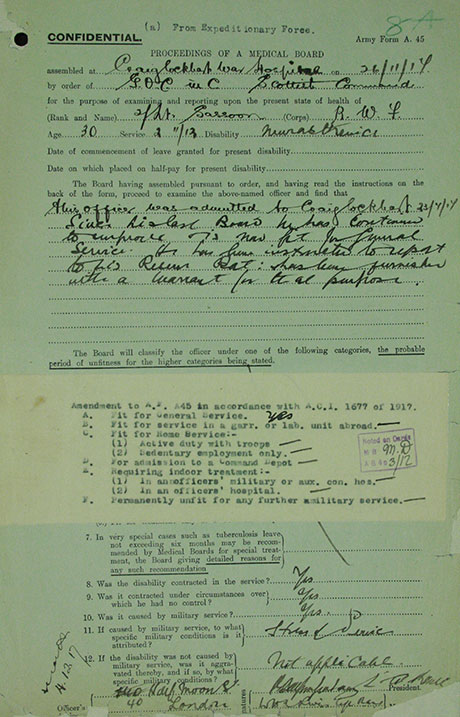

Rather than court martial a war hero and published poet, it was decided that Sassoon should go before a medical board and be declared unfit due to nervous exhaustion. The board’s recommendation was that Sassoon should be admitted to Craiglockhart, a military psychiatric hospital in Edinburgh for the treatment of shell-shocked officers.

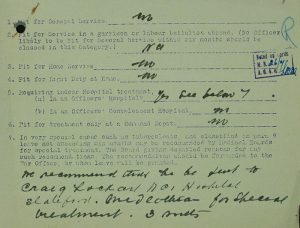

- Report of medical board held on 28 July 1917

- Recommendation that Sassoon be admitted to Craiglockhart

This meant that Sassoon did not take part in the Passchendaele campaign, but his poem ‘Memorial Tablet’, written in October 1918, shows that he was keenly aware of the men’s suffering and the indifference of those at home. The poem is narrated by a soldier who was ‘nagged and bullied’ to enlist by the local squire, who stayed safely at home. He describes his death during the battle:

‘I died in hell—

(They called it Passchendaele). My wound was slight,

And I was hobbling back; and then a shell

Burst slick upon the duck-boards: so I fell

Into the bottomless mud, and lost the light.’[ref]1. © Literary estate of Siegfried Sassoon. Please direct any enquiries to the Barbara Levy Literary Agency[/ref]

Sassoon was declared fit for general duties at a medical board at Craiglockhart on 26 November 1917. Despite any misgivings on the part of the War Office and his own previous refusal to return to duty, he was promoted to Lieutenant and returned to active service. He had wanted to be posted to Italy or France, but in March 1918 he was posted to a unit serving in the relative safety of Palestine and promoted to Acting Captain. However, in May 1918 Sassoon’s wish to be at the centre of the action was granted when his battalion was sent to the Western Front.

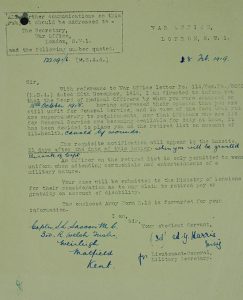

Report of medical board held on 26 November 1917

Sassoon continued writing poetry and the War Office had not lost interest in his implied criticism. On 20 July 1918 the editor of the Nation received a letter asking whether Sassoon’s Poem ‘I Stood With the Dead‘ – published in the issue of 13 July 1918 – had been written after his return to service in November 1917. The reasoning was that his mind must still be in chaos if he was writing such poems and he was not fit to be trusted with men’s lives.

Almost immediately on his return to the Western Front Sassoon was wounded in the head, shot by a fellow British soldier who mistook him for a German. Once again he was repatriated to England; a medical board held on 18 October 1918 found that he was still unfit for general service. A letter from the War Office informed Sassoon:

‘You are still unfit for General Service and in view of the fact that you are supernumerary to requirements, now that officers who are fit are becoming available for duty at home it has been decided to place you on the retired list on account of ill health caused by wounds. The requisite notice will appear in the Gazette when you will be granted the rank of Captain.’

- The page from The Nation with Sassoon’s poem ‘I Stood With the Dead’

- Letter informing Sassoon that he was to be put on the retired list

The war that had caused so much agony was over and the Army was able to retire Sassoon from service without controversy.

Sassoon was a brave officer who served with distinction and cared about his men. He had shared the appalling conditions and agonies of fighting on the Western Front and felt that he could no longer condone the continuance of such a war. In ‘Memorial Tablet’ he aimed to bring home the brutal truth of what the men must have suffered at Passchendaele to a public that was largely indifferent to what was going on, and ignorant of the horrors of the trenches. The poem vividly records with anger, and some bitterness, the horror and pointless sacrifice of what Sassoon saw as the hell of Passchendaele.

Further reading

Jean Moorcroft Wilson: Siegfried Sassoon, The Making of a War Poet: Gerald Duckworth 1998

There was of coursed censorship for the British people over what was going on during the First World War (and that censorship still applies) to conflicts so it is no wonder that people were ‘in the dark’ over the deprivations and military problems.

And yet, men like Sassoon came home on leave, and the war poets published in publically accessible venues. While so many marched, imbued with patriotism, the reality became much more…yet most people then, as as now, continue/d to believe what enabled them to continue on, to remain ‘patriotic….patriotism defined as the act of flag waving, NOT the act of thought.

Thank you for this valuable post, containing documents many of us have never seen before.

[…] Passchendaele – Sassoon’s hell […]