Detail from the Jesse Cope (c.1310-25), showing the Virgin Mary and Child © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

On Monday 7 November, members of The National Archives’ Medieval and Early Modern teams visited Opus Anglicanum, the Victoria and Albert Museum’s exhibition about medieval English embroidery. In this post we’re going to take a closer look at the exhibition and introduce some of the many records The National Archives holds which relate to medieval fine cloth and clothing.

In the 14th century English craftsmen and women were renowned for the exceptional quality of their work. England exported, through sale and as gifts in international diplomacy, innumerable pieces to the Papacy and royal and noble houses across Europe. Much of what we do here at Kew involves poring through documentary evidence to get clues about what life was like in the past, but it’s rare that we get to work with objects.

Some of our highlights from the exhibition included a selection of fine copes (heavily decorated cloaks which were used by members of the clergy when performing their liturgical duties), including one from just down the river at Syon! The Syon cope was originally coloured with bright red and green silks, although over the years the bright red has faded to a pinkish brown, and the green colour has also faded slightly. It is, however, still magnificent, and features incredibly detailed images of Christ and various saints, often with the instruments of their martyrdom, like the gridiron of St Laurence.

The vivid colouring of these medieval vestments became clear as we viewed some of the other vestments. The bright red cope depicting the Tree of Jesse (a common theme in medieval art which depicted Jesus’s family tree), retains much of its original colouring and detail despite some damage over the years.

The Clare Chasuble (c.1272-94) © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Red was not the only colour used for the production of vestments, however. The 13th century Clare Chasuble (the main vestment worn by priests when celebrating mass) shows the use of a rich blue colouring, with golden embroidery depicting biblical scenes alongside lions and griffins.

The Clare Chasuble is of particular interest as it features the arms of Margaret de Clare and Edmund Plantagenet, earl of Cornwall (as well as the royal arms of England), indicating that it was probably used by someone in their household. Margaret, sister to the powerful earl of Gloucester, had married Edmund, cousin of King Edward I (1272-1307), in October 1272. The marriage was not happy and resulted in the couple undergoing a formal separation in 1294, Edmund having been excommunicated for refusing to cohabit four years earlier.[ref]1. Nicholas Vincent, ‘Edmund of Almain, second earl of Cornwall (1249-1300), magnate’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.[/ref]

We have several documents in our collection relating to Margaret de Clare, including the Inquisition Post Mortem assessing her lands after her death in 1312 (C 134/28/4), and petitions to the king defending her lands and rights (SC 8/39/1926 and SC 8/275/13738). The chasuble, however, is spectacular evidence of the rich exchange of gifts and vestments at the English royal court between the king and his close family circle.

Our documents relating to medieval embroidery

As the exhibition and its superb catalogue demonstrate, references to the different types of vestments on display at Opus Anglicanum – ecclesiastical robes, heraldic horse trappings and costly embroidered clothing – abound in our records.

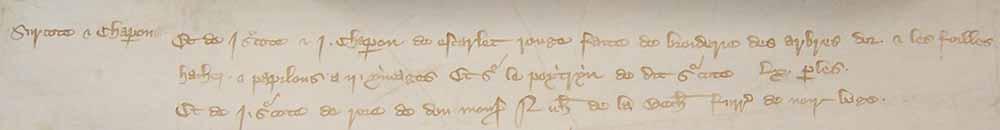

Those for the royal court are frequently found in E 101, one of the most rich and diverse series of medieval records in our collection. Accounts for the Royal Wardrobe covering 1336-8, for example, record the manufacture of a surcoat and hood of red scarlet embroidered with golden trees and fallen leaves, butterflies and two (unspecified) images; the stomach area of the garment is studded with 60 pearls.[ref]2. E 101/387/25, m. 7[/ref]

A red scarlet surcoat and hood embroidered with trees, leaves and butterflies, etc. (catalogue reference: E 101/387/25, m. 7)

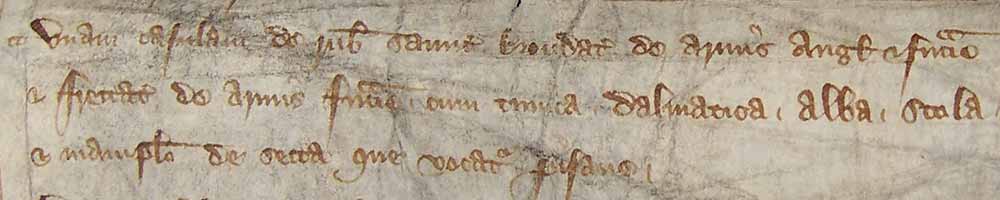

Accounts can also be found among the records of the royal household, in supplying liturgical vestments for members of the Chapel Royal (the king’s personal itinerant choir) and for those priests who served in the private royal chapels found in royal residences. An indenture by which custody of Edward III’s great wardrobe was transferred between keepers in 1349 reveals a red samite (silk) chasuble embroidered with the arms of England and France and fretted with the arms of France, with a dalmatic tunic, alb, stole and maniple of the set which is called Pisane.[ref]3. E 101/391/19[/ref]

A red samite (silk) chasuble embroidered with the arms of England and France, etc. (catalogue reference: E 101/391/19)

The lengths to which royal embroiderers occasionally had to go is evidenced in a roll of liveries of cloth and furs from 1337-8. There, Thomas de Crosse, clerk of the great wardrobe, accounts for seven pecks each of white and red buckram (a fine linen or cotton cloth, often used to line other garments), four ells of russet cloth, 600 gold leaves, 1300 silver leaves, 22 bullock hides, two pounds of variously coloured yarn, 86 plain masks, 14 masks with long beards, and 12 ells of canvas.

These were fashioned into a rabbit warren made from timber, covered in canvas and painted to resemble a wood of diverse trees, a pillory and a shelvyngstol, 15 baboons’ heads of linen, 12 white buckram surcoats with red buckram sleeves decorated with gold leaves, four buckram mantles and 15 red and white buckram tunics ornamented with gold and silver, 15 hoods of the same livery, a tunic of russet and 13 iron caps. These were made for the king’s games at Christmas, and payments were also made for the stamping of tunics, hose and gloves for the baboons, as well as for their sewing and the safe custody of the masks.[ref]4. E 101/388/8, m. 5[/ref] Christmas must have been a very grand occasion in Edward III’s court!

Account for the creation of a fantasy woodland setting and liveries for the king’s party at the Christmas games, 1337-8 (catalogue reference: E 101/388/8, m. 5)

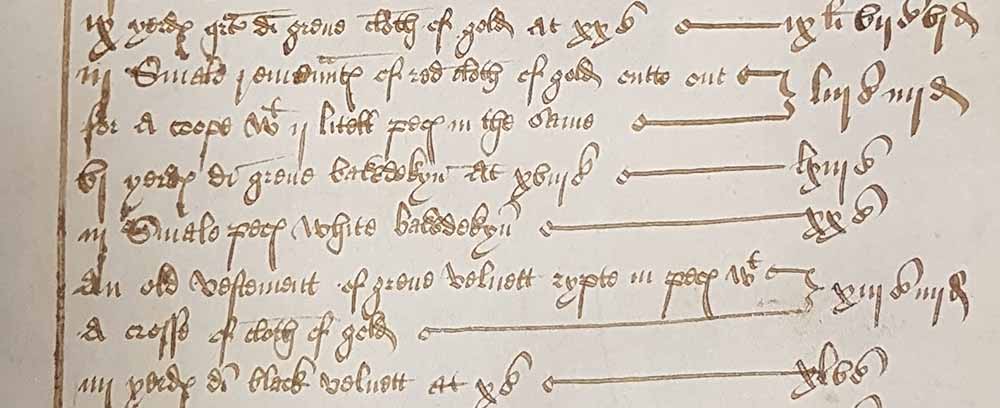

A clear theme which came out of the exhibition was the way in which old embroidery could be recycled into new products, with a little bit of tailoring and refinement. Even the most wealthy men in society were not beyond using second-hand cloth in their vestments, as our records show. Nicholas West, bishop of Ely (d. 1533), was an extremely rich man at the time of his death, leaving behind an estate worth £1665 (with a further 5060 oz. of silver and gilt plate) but the inventory of his goods also included recycled vestments and cloth.[ref]5. Felicity Heal, ‘West, Nicholas (d. 1533), bishop of Ely and diplomat’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography[/ref] These included small pieces of ‘red cloth of gold cutte out for a coope [cope]’, with two further little pieces (worth 53s. 4d.), and ‘an old vestement of grene velvet rypte in pec[es] w[i]t a crosse of cloth of gold’ (worth 13s. 4d.).[ref]6. PROB 2/488[/ref]

The probate inventory of Nicholas West, bishop of Ely (catalogue reference: PROB 2/488)

The exhibition’s curators, Claire Browne and Michaela Zöschg, were kind enough to meet us for a chat in the tea rooms after our visit, and to answer some of our questions about medieval embroidery production and the way in which they had put the exhibition together. They explained that the exhibition had taken all of five years to plan, and includes artefacts from all over Europe! They explained a bit more about the technical processes which medieval embroiderers would have used to construct magnificent vestments for the use of the elite clergy, including the use of very fine gold and silver metal stitching to give an magnificent and dazzling finish. Seeing these embroidered items up close gives an impression of just how visually powerful medieval religion and ceremony was, and helps us to picture how some of the embroidery in our documents would have looked. It’s just a shame that none of Edward III’s baboon heads survive!

Opus Anglicanum runs until Sunday 5 February 2017.

For more on the history of medieval cloth and clothing, have a look at the richly detailed website of our academic partners Lexis of Cloth and Clothing Project. Work from the project will be on display in the Keeper’s Gallery until March 2017.

Further reading

Richard Barber, ‘Edward III and the Triumph of England’ (London, 2013)

[…] techadmin on December 16, 2016 Opus Anglicanum: medieval embroidery and fashion2016-12-16T10:00:11+00:00 – Journals & Publications – No […]

Thanks for sharing the info.

very nice collection i appreciate 🙂