Last week’s presidential elections in the United States were as enthralling as ever. As the polls showed a closing gap between the candidates in the preceding weeks, and media attention sky-rocketed, tensions were high by the time the votes were being counted. The announcement of the victor (it was Barack Obama, by the way) led, the next day, to the expression of many messages of congratulation. One thing has always intrigued me: how do the telephone calls of congratulations between world leaders go? Do these messages really express a desire to reaffirm special relationships, or are they more bland?

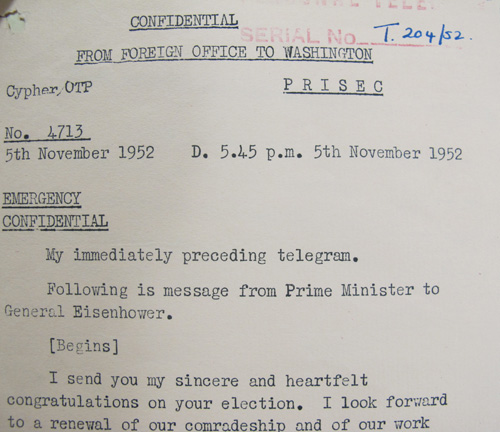

Churchill congratulates Eisenhower in 1952 (PREM 11/572)

A couple of Prime Minister’s Office files – PREM 11/572 and PREM 15/1980 – detail two very different communications between the political leaders of the United Kingdom and the United States, even if some of the underlying aims of their ongoing co-operation are remarkably familiar.

The first of the files begins with a simple note from Winston Churchill, Prime Minister for the second time, from 1951-1955, congratulating President Dwight Eisenhower on his victory in 1952. Churchill wrote:

‘I send you my sincere and heartfelt congratulations on your election. I look forward to a renewal of our comradeship and of our work together for the same causes of peace and freedom as in the past. Winston.’

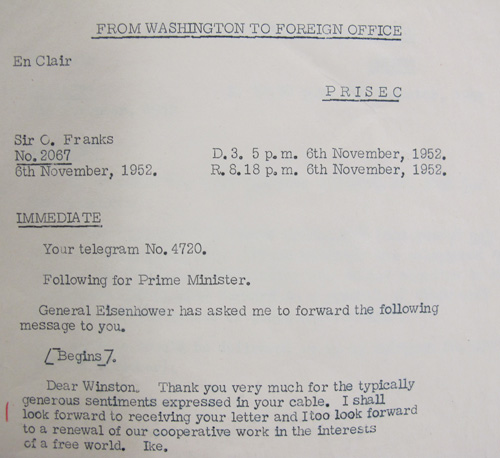

The next day, Eisenhower replied:

‘Dear Winston. Thank you very much for the typically generous sentiments expressed in your cable. I shall look forward to receiving your letter and I too look forward to a renewal of our cooperative work in the interests of a free world. Ike.’

Eisenhower responds (PREM 11/572)

This brief communication hints at a camaraderie between two statesmen forged during the recent years of war, and an apparently genuine desire to work together to ensure freedom in the world (even if the general’s note does not mention ‘peace’). Indeed, a more thorough investigation of Churchill’s second premiership than can be given here would indicate that he was driven by a desire to leave as his political legacy a peaceful world, as the Cold War set, and especially after the development of the destructive power of the hydrogen bomb in the mid-1950s.

Nevertheless, even as Churchill and Eisenhower exchanged these messages espousing peace, the Korean War was ongoing. Later in the same file the comments of a senior British military official who travelled to Korea with Eisenhower reported two interesting points the President expressed: that it might be possible to establish an alternative regime in China, and that the lobby for employing Chinese nationalist forces to enforce this was strong (even if it was unclear whether Eisenhower was impressed by such arguments). Those, perhaps, were the ‘interests of a free world’ he alluded to.

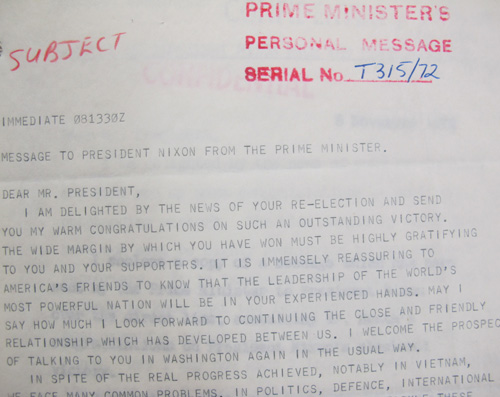

Heath congratulates Nixon in 1972 (PREM 15/1980)

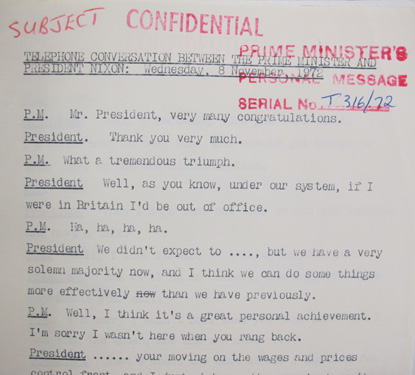

Twenty years on, and Prime Minister Edward Heath congratulated President Richard Nixon for his re-election with a telegram and also a telephone conversation, a transcription of which is available in the PREM 15/1980 file. The telephone call is illustrative as there is a brief discussion about policy (Nixon wishes Heath well on his attempts to control prices and wages), some somewhat stilted conversation in which Heath congratulates Nixon five times (perhaps especially due to the extraordinary size of Nixon’s victory), and an apology from Heath who missed Nixon’s return call because he was with The Queen (‘the best excuse I can find for anybody’, quipped the President).

Transcript of Heath and Nixon's telephone call in 1972 (PREM 15/1980)

The message from Heath which preceded the call spoke of the real progress achieved ‘notably in Vietnam’ as well as a desire to tackle shared difficulties together (in their conversation Nixon said, ‘One last thing. In privacy, the Vietnam thing is going well’). Heath also added, ‘you must be particularly happy that you will be President of the United States in 1976, the 200th anniversary of the independence of your great nation. It will be a notable anniversary.’ Which all goes to show that nothing can be taken for granted in politics.

These two files show two very different personal relationships between Prime Ministers and Presidents, but the fortunes of their countries appeared to remain shared, with notions of peace, democracy, and the defence of those principles at the fore.

And of course Nixon had to deal with Watergate and the cover-up over attempts to get to the truth which ended with Nixon’s resignation, the onluy US Presient forced to do so. The situation in Vietnam may have seemed to Nixon to be going well but it wasn’t and consisted of carpet bombing and the US forces and staff escaped by helicopter fom Saigon after the Communist forces approached Saigon. The US and the UK do not always share the same interests especially over Vietnam where Harold Wilson was not prepared to put the UK into the war and the Foreign Office admitted that the ‘Special Relationship’ was not special (see the files at TNA) but the two countries worked with whoever was in power.

David,

Your last point is particularly pertinent – whether both countries frame it as a ‘special relationship’ or not, the co-operation between the US and the UK in the post-war period is remarkable, whichever parties or leaders are involved. The background of military conflict is another, darker recurrence.

Simon

Simon,

I wouldn’t argue that the ‘Special Relationship’ has worked well especially when Britain was bankrupt from 1943 through to the early 1950s but there have been tensions particularly over Suez when the Americans (rightly) would not give money to support Sterling and the operation collapsed. The Americans of course were also responsible for funding the post-Second World War reconstruction of Western Europe and the mistakes of the post-First World War by the UK (why didn’t people listen to Keynes?) were largely avoided. In some regards the British Prime Minister was obliged to congratulate the incoming President and vice-versa. You can understand the relationship between Churchill and Eisenhower as they had key key parts during the Second World War.

David