The Gallipoli landings, their failure, and the subsequent evacuation of the peninsula are often referred to by students of the First World War, and especially those who, rightly, wish to analyse and discuss the global aspects of the War – far from the Western Front.

In The Cambridge History of The First World War, Robin Prior notes that around August 1915 the ‘evacuation [of Gallipoli] was discussed in London but there was a Cabinet rebellion. British prestige, it was said, could not withstand such a humiliation’.

However, by December 1915 it was clear that (with victory in the War obviously more important than individual successes or failures) the extraction of the troops from Gallipoli had to be undertaken. When studying a campaign or specific battle from the First World War there are a number of primary sources one can refer to; war diaries, official histories, maps and plans to name but a few. However, a great source for analysing policy, diplomacy and controversy is of course the records of the Cabinet Office. These records, held by The National Archives in the record series ‘CAB’, are an excellent method of analysing what our politicians – the people responsible for making the decisions that start and end wars – were thinking at times of great drama in history.

The First World War is no exception to this.

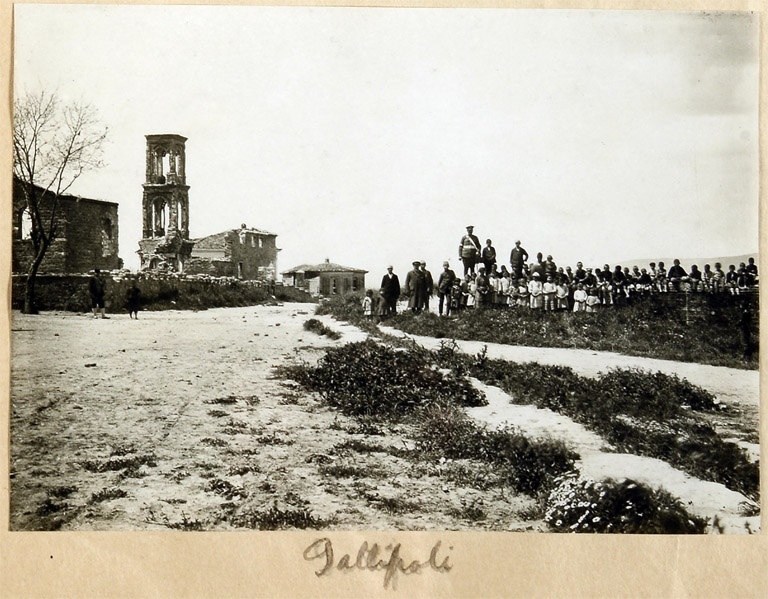

The initial plan for the Gallipoli landings was for British, Australian, New Zealand and French forces to engage Ottoman troops directly, relieving pressure on the Russians in the Caucuses. This would theoretically lead to the diversion of Central Power troops from the Western Front. The invasion failed and stalemate set in, with attempted remedies, such as the British offensive at Suvla Bay in August 1915, failing to break the deadlock.

As the cabinet papers indicate, discussions took place about the benefit of withdrawing troops from Gallipoli and refocusing these Allied forces elsewhere. However, the withdrawal of troops from the Gallipoli peninsula was a hotly debated topic in both the Cabinet and the War Committee, with both bodies unable to agree on the next step for the campaign and the troops committed there.

Indeed a paper presented to the Cabinet on 19 November 1915 (CAB 37/137/36) produced by Arthur Balfour states that although he was:

‘aware that many of my colleagues, both in the War Committee and in the Cabinet, are strongly in favour of the abandonment of the Gallipoli Peninsula… I am as reluctant to abandon it as I should be to abandon any other fortress… [through] such an abandonment we should lose credit in our own eyes, in those of our enemies and in those of our friends.’

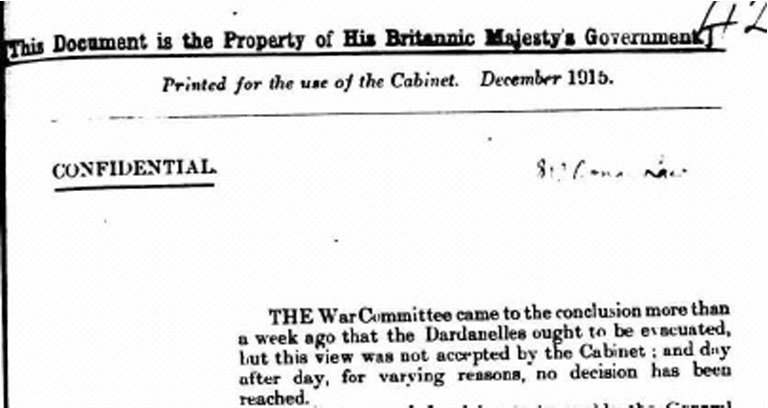

Andrew Bonar Law acknowledged the general split between the War Committee and the Cabinet in his paper to the Cabinet dated 4 December 1915 (CAB 37/139/12) stating that due to this difference of opinion ‘Day after day… no decision has been reached’.

Excerpt from Bonar Law’s paper to the Cabinet dated 4 December 1915 (catalogue reference: CAB 37/139/12)

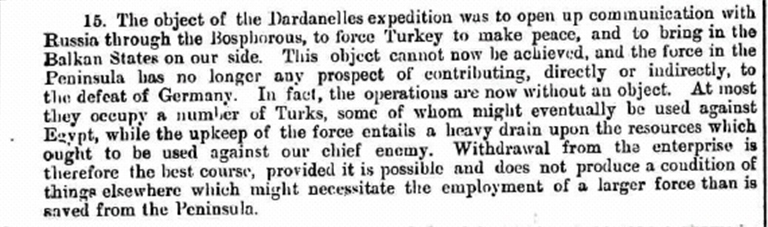

Bonar Law wrote passionately about the existence of the War Committee being due to a body ‘so large’ as the Cabinet not being appropriate to administer a war. He pleaded with his colleagues in the Cabinet to respect the fact that ‘every military authority, without a single exception whom we have consulted, has reported in favour of an evacuation’ including, Lord Kitchener, General Robertson and General Archibald Murray. Indeed, in his paper to the Cabinet on 8 November 1915 Robertson wrote that ‘the force in the peninsula has no longer any prospect of contributing directly or indirectly to the defeat of Germany… withdrawal from the enterprise is therefore the best course’ (CAB 42/5/6).

Finally, after much toing and froing and with the loss of prestige in one hand and the obvious failure of the campaign in the other, at a War Committee meeting on 6 December 1915, Sir Edward Grey is recorded as noting that ‘there was obviously only one thing to be done’ concerning Gallipoli, implying that he supported the evacuation of peninsula by Allied forces (CAB 42/6/4).

A Cabinet Memo arranged for Buckingham Palace, by 10 Downing Street and the Office of Prime Minister Asquith, signed 7 December 1915, states that the Cabinet had finally arrived at ‘its final decision with reference to Gallipoli’. The Memo confirms that the cabinet now believed ‘there was no alternative but to proceed… with the evacuation of the positions at SUVLA & ANZAC’ (CAB 37/139/17).

Therefore despite the previous protestations of cabinet members including Balfour, Austen Chamberlain and Lord Curzon, the evacuation of the peninsula was finally deemed as strategically and logistically sensible, and thus, so began the withdrawal on 15 December 1915.

The cabinet records – many of which have been digitised and are available to download on Discovery, our catalogue (and via Cabinet Papers online), indicate that in the tumult that was the First World War, leading political figures were often unsure, regularly disagreed with each other and compromised and improvised as they tried to navigate through the difficulties and stalemates of the conflict. They are an invaluable source to the student of the period and there are many historical treasures within, as can be seen from the small selection above dealing with the evacuation of Gallipoli following the ill-fated campaign, a campaign which came to an end, upon the retreat of the Newfoundland Regiment’s rear-guard, 100 years ago.

The evacuation itself was a relative operational success, especially when compared to the previous 8 months, and casualties between 15 December 1915 and 9 January 1916 were low. However, when viewed as a whole, the campaign was an unmitigated failure and as Prior notes in his text ‘Gallipoli – The End of the Myth’, ultimately the operations on the Gallipoli peninsula ‘did not shorten the war by a single day’.

Further reading

Prior, R., ‘The Ottoman Front’ in Winter, J. (Ed.), The Cambridge History of the First World War: Volume 1 – Global War, Cambridge University Press, 2014, pp. 297-320

Prior, R., Gallipoli – The End of the Myth, Yale University Press, 2009

So awful – so many slaughtered Australians and allies all so Britain could save face.

Lindsay M

Sydney ex UK

You’ve misinterpreted the facts: Prior to the evacuation, it was contested based on whether or not the campaign could still be salvaged for strategic value; deny the Central Powers the support they required on the Western front.

Eventually, it was concluded that the Gallipoli campaign was a failure. Only then did the evacuation debate become about prestige, though this debate was very brief and it was quickly decided to evacuate the troops anyway.

In short, it’s disappointed that the British politicians would even consider abandoning our Anzacs and allied soldiers to save face, but ultimately the decision was made to evacuate the peninsula with little overall support for abandoning the troops or continuing the campaign.

The campaign was doomed to fail from the outset. Had the British parliament recognized this eight months prior to the evacuation, few (if) any lives would have been lost at Gallipoli. Saving face was always a secondary concern with little real support and it was very quickly overruled in favour of evacuating Gallipoli. However, it remained a soured event between Britian and the Anzac commanders during and after the war.

Hello James,

Re: Gallipoli evacuation

Hope it’s OK to check these:

” … cabinet members including Balfour, Joseph Chamberlain and George Curzon …”

1 This should be Austen Chamberlain, not Joseph?

2 George Curzon – should be called Lord Curzon?

Sincerely,

Robert A

Hi Robert,

Thanks for your comment, we’ve updated the blog.

Best,

Nell

Of course it’s hard to describe anything in ear as a “success,” so really impossible to know whether Gallipoli was a failure. I always think it’s surprising when we talk about “winners” and losers of battles or war…surely we’re all just people? How can we say “Germany” “lost” either the first or second war when so many people died?

But great blog! Long live the PRO!