As young children around the country write and draw about their holiday experiences, with concentrated stares and sticking-out tongues, I too reach to the what-I-did-on-my-holidays September staple.

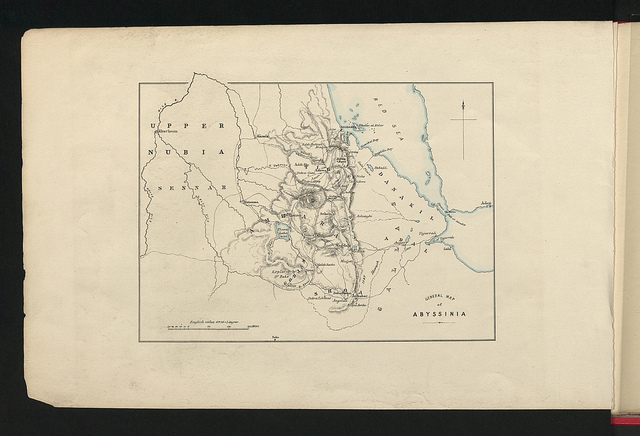

General Map of Abyssinia - Africa Through a Lens (CO 1069/7/2)

Or, rather, I found inspiration from my recent trip to Ethiopia to take a look in some Foreign Office files relating to the country. My time there – alongside regular rainfall and cool temperatures (just like earlier in the summer here, really) – was dominated by the period of mourning following the passing of the Prime Minister Meles Zenawi.

One piece of information particularly interested me: that Meles attended the British-funded and -inspired General Wingate Secondary School just outside of Addis Ababa (which, incidentally, my father also attended, two years his senior). The school had been in somewhat of a decline but was rescued due to an injection of finances from the British Council in the early 1960s. Consequently, a number of records – mostly relating to the financing of the school – are available here at The National Archives, as a result of discussions between the British Council, the embassy, and the school itself. A quick search in Discovery provided an intriguingly titled record: ‘Wingate School, Addis Ababa: student disturbances following Rhodesian Unilateral Declaration of Independence’ (FO 1043/53).

In November 1965, following a referendum which had backed independence and black majority rule the year before, Ian Smith’s ruling Rhodesian Front Party sought a way to resist such measures by announcing a Unilateral Declaration of Independence. This caused consternation not only for the British Government, but for many people across Africa.

Addis Ababa was then the home of the Organisation for African Unity (OAU) – and still hosts its successor organisation, the African Union – and the students at the Wingate School found cause to protest outside the OAU headquarters. The 200-strong demonstrators had cut classes in order to protest and the file describes the reaction by the school, as the headmaster Alan King reported to the British Council about the events. Concern was high both within the school and the Council because a similar demonstration was running concurrently outside the British Embassy, even though no Wingate students attended that protest.

King, however, seemed more concerned with the possibility that OAU or Ethiopian Imperial Government ‘plants’ might have been operating within the school, which would indicate a potential political influence within the school. He told an official high in the Ethiopian Ministry of Education that anyone involving the Wingate in politics might ‘…compromise the new agreement [to keep the school open] and the whole future of the school in its present form.’ Indeed, his stern assembly to the school following these events (‘…do not flout authority’; ‘…if you want to make your own rules then go somewhere else to do it! Not in this school!’) demonstrated his desire to resist any politicisation of the school, and some fairly classic English public school principles.

King also indicated another interesting point, noting in a missive to the British Council that the students on the whole had ‘the woolliest of notions on Rhodesia, and the great majority showed dislike for “One man, One vote”.’ There was talk of ‘uncivilised blacks’, ‘illiterate savages’, ‘natives’, and ‘barbarians’. This could be an attempt by the headmaster to assure the Council that politicisation at the school had not taken root, but 200 demonstrating students might suggest otherwise.

This file shows us many things: that political intrigue in one country can have its effects in unlikely places; that pan-Africanism (the yellow, green, and red of Ethiopia’s flag was adopted as a symbol of African independence) manifested itself – and was challenged, considering some of the language used – in a number of ways; and that the influence of British soft power went beyond the boundaries of its empire. But on a personal level it gave me pleasure to engage in a little bit of family history in the archives, particularly when I discovered to my delight that my father was on that very demonstration. Although I was surprised that he did not remember the headmaster’s fiery assembly.

Well summarised sir. This schoolboy has no memory of the incredoulous qoutes reported by mr king. History comdemns those who confabulated.