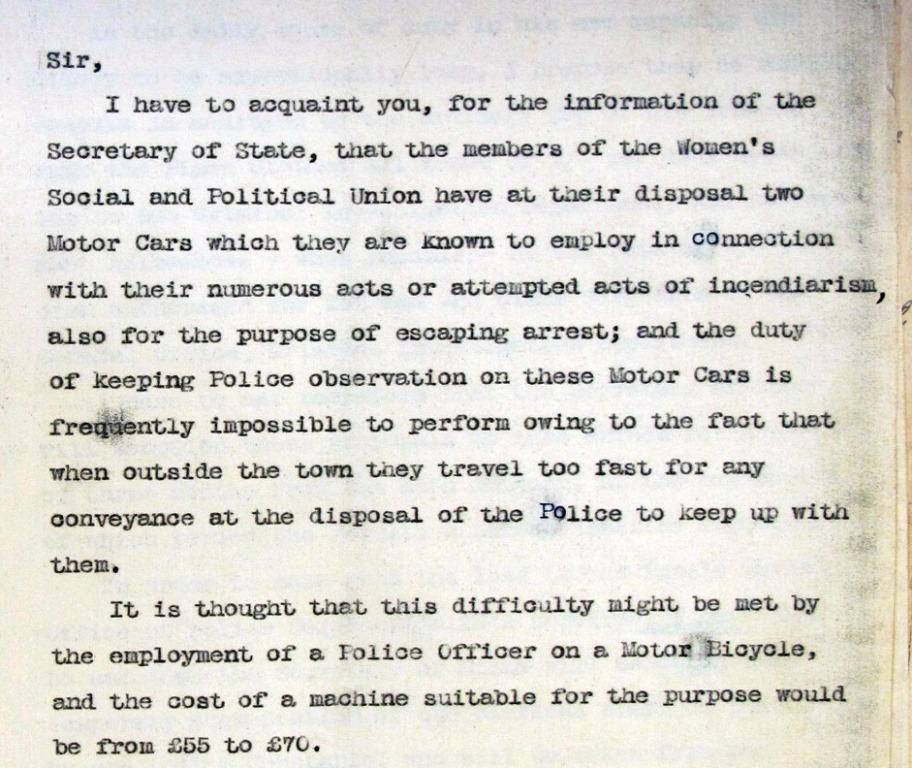

Letter showing the Metropolitan Police requesting a motorbike to keep up with the WSPU drivers (MEPO 2/1566)

One of the best things about working at The National Archives is stumbling across items you never knew were there. My most recent discovery was a police report into the suffragettes’ use of motor cars. At the time this did not fit the role generally expected of women, at worse it was often perceived as masculine and an act of subversion. It seems that the history of women driving has always been a little bit controversial.

The file MEPO 2/1566 shows the Metropolitan Police requesting a motorbike to keep up with the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) drivers. Essentially the suffragettes were able to use these vehicles to outwit the police. The document notes that the members of the WSPU were using a least two cars ‘in connection with their numerous acts or attempted acts of incendiarism, also for the purpose of escaping arrest’ (MEPO 2/1566). From 1913 firebombing and arson attacks had become common suffrage tactics, our records hold many examples of suffragettes arrested for these types of offences.

The physical freedom that driving, and indeed cycling, provided women near the turn of the century was radical. It gave women a freedom they were previously not allowed. Bicycles were associated with caricatures of the ‘New Woman’, a defiant figure representing female emancipation. The image opposite shows a ‘New Woman’ caricature, switching the traditional domestic roles of husband and wife. Cars often meant women could not be chaperoned, they had a degree of freedom of movement they were often not able to have before. In practice it often meant women had to change their clothing to more practical trousers, and more ‘masculine’ wear. It held a fear of subversion: women acting like men were seen as a threat because they questioned the accepted social hierarchy.

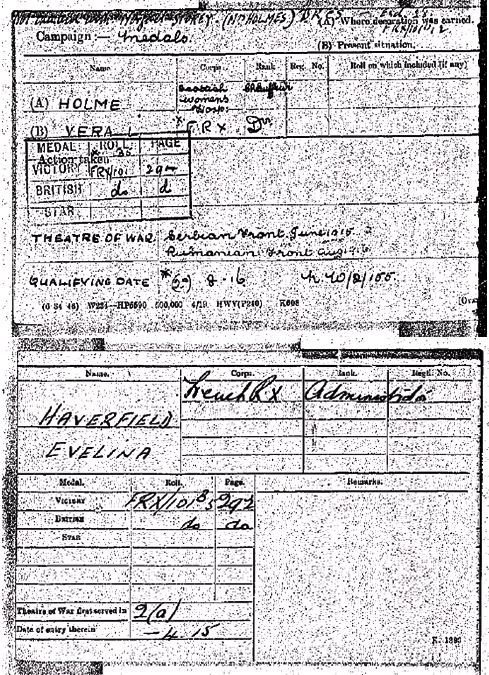

Vera Holme almost epitomises this fear. In 1909 she became Emmeline Pankhurst’s driver, and she wore masculine clothes, smoked, and lived by independent means all of which went against traditional ideas of femininity. Holmes chose to be referred to as ‘Jack’ and was known to have relationships with women. [ref] 2. Wendy Parkins, Fashioning the body politic: dress, gender, citizenship, 2002, p. 128. [/ref] It shows that women being able to drive had many more associations for society other than the physical act of driving.

Vera not only drove for the suffragettes but from 1915, like many women fighting for the franchise, she turned to support the war effort. First she became a chauffeur for the Scottish Women’s Hospital and then a driver for the French Red Cross, as her medal card shows. The war enabled Vera to take on roles she had previously been condemned for. We also have the medal card of her life long partner Evelina Haverfield who served in Serbia as an administrator for the French Red Cross.

This awareness of women’s changing role and its perceived link to women having relationships with women is also emphasised in Radcliff Hall’s novel The Well of Loneliness. The war work enables the central character Stephen, described by Hall as an ‘invert’, to live a more masculine life. Stephen serves in an ambulance unit and falls in love with fellow driver Mary Llewellyn. Although published in 1928 amid the furlough of an obscenity trial, it captures some of the contemporary fears relating to women’s changing role and war work. The central character is thought to be based on Toupie Lowther who led the only all-women team of ambulance drivers and whose medal card we also have.

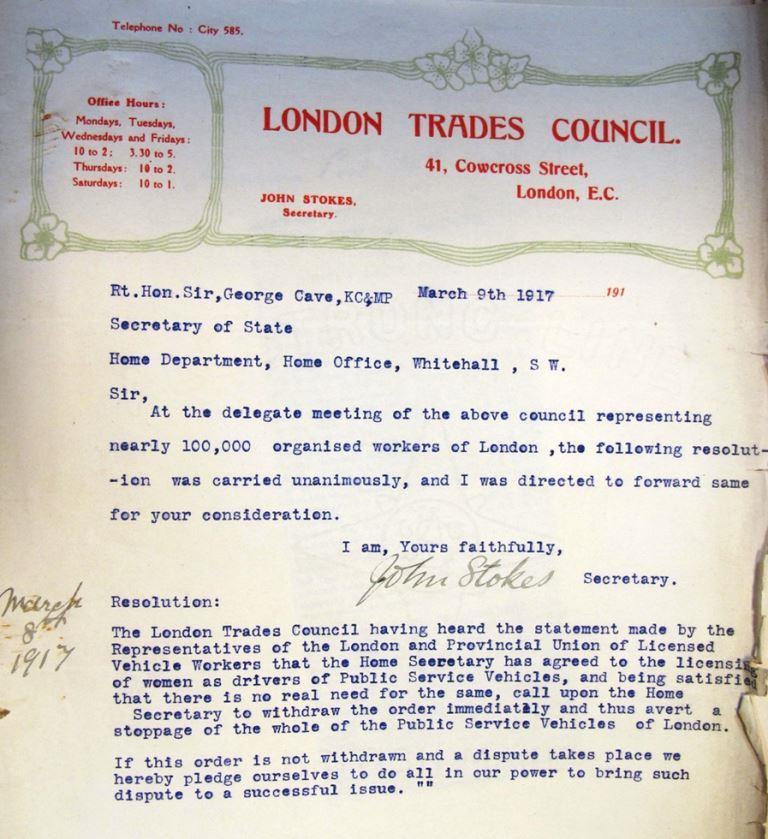

Letter from the London Trades Council giving an ultimatum demanding the repeal of women’s driving licenses and threatening a strike of their 100,000 strong workforce (HO 45/11164)

Women drivers were clearly essential for the war effort but they were far from being without controversy. This was apparent on the home front where women were needed to take up other jobs to enable men to serve on the front line; this was seen as a ‘matter of urgent military importance’ (HO 45/11164).

Women drivers were needed to support munitions work and on the omnibuses to enable workers to travel. However the licencing of women as omnibus drivers proved to be very controversial. A compromise was eventually reached which allowed women to have omnibus licences only for the duration of the war. A letter to the Home Office from the Women’s Freedom League, who continued to fight for women’s equality during the war in numerous ways, made their position clear:

‘We feel that at a time like the present when women are being called upon more and more to take part in the work of the nation (pleasant and unpleasant) it would be a very dangerous thing for those in authority to concede to any section of men the right of refusing to allow women to enter their industry.’ Letter to the Home Office from the Women’s Freedom League HO 45/11164, 16 March 1917

The response to this can be seen in the Home Office correspondence, the London Provincial Union of Licensed Vehicle Workers state there were “strong moral grounds why women should not be so employed’ (HO 45/11164).

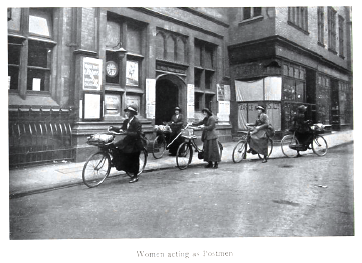

Photograph of women postmen from the government publication Women’s War Work, September 1916 (MH 47/142/1)

This eventually lead to an ultimatum in 1917, when the London Trades Council sent a resolution demanding the repeal of women’s omnibus licenses and threatened a strike of their 100,000 strong workforce – just to prevent women driving. The male trade unionists felt women entering the workforce would drive down men’s wages upon their return.

It is interesting that even in the context of war it was hard to break down these gender barriers.

Despite the controversy many women did successfully contribute to the war effort through driving. The following image from the War Office publication Women’s War Work (September 1916) shows a pride in the work women were undertaking for the war effort.

MH 47/142/1 – Photograph of a women driving a motor van from the government publication Women’s War Work, September 1916.

So next time you hear a joke about women drivers consider the history to it – they were almost driven away from the roads a century ago.

[…] Motoring towards liberation […]