Image of ‘Jack Tar’ (a common term for sailors) by Harry Payne, 1893. Catalogue reference: COPY 1/108/436

Let those who have never seen a ship of war, picture to themselves a very large and very low room with 500 men and probably 300 or 400 women of the vilest description shut up in it, and giving way to every excess of debauchery that the grossest passions of human nature can lead them to […] 1

At a time when the health of Britain’s armed forces was crucial if they were to continue to control the Empire, scenes such as the one described above were causing great alarm within the government. Between 1864 and 1869 three laws – which became known as the Contagious Diseases Acts – were passed in an attempt to prevent the spread of sexually transmitted diseases which were seen to be debilitating Britain’s army and navy. 2 According to government sources, nothing short of the security of the nation itself was at stake. 3

In port or garrison towns, the Contagious Diseases Acts gave the police powers to stop any woman suspected of being a prostitute. They could bring her before a magistrate, who, if he agreed with the police officer, would subject the woman to a forcible examination by speculum. 4 If any signs of sexually transmitted disease were noted, the woman would be sent to a ‘lock hospital’, where she was kept under lock and key until her symptoms disappeared. 5

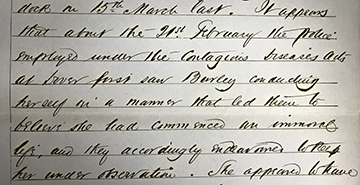

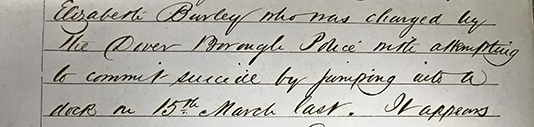

Details of the police monitoring Elizabeth Burley, of Dover, as they thought she might be liable for detention under the Contagious Diseases Acts. Catalogue reference: HO 144/78/A4010

The Contagious Diseases Acts raised a number of issues, most notably the rights that women had over their own bodies. As early as the late 1860s, small campaign groups were opposing the Acts, but the repeal campaign didn’t reach its peak until the 1880s. 6 Josephine Butler, the wife of an Anglican minister, emerged as one of the leading campaigners to repeal the Contagious Diseases Acts. Butler called the examinations by speculum ‘instrumental rape’ and argued that keeping women in ‘lock hospitals’ deprived them of their basic rights.

The government continued to claim that the acts were necessary, and even successful. However, the case of Elizabeth Burley in Dover in 1881 galvanised the public further in calling for the Acts to be repealed. 7

As one of Britain’s main ports, Dover came within the scope of the Contagious Diseases Acts. 8 In 1882, Metropolitan Police statistics revealed that, on average, 56 women were registered as prostitutes in Dover each year; more than 12,000 women had been examined under the legislation. 9 Dover consistently had the second highest number of arrests for prostitution in the country. 10

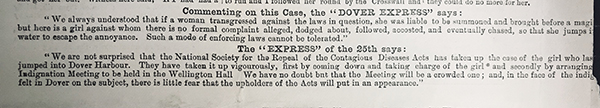

An account of how Elizabeth Burley was chased by police, who thought she may be a prostitute liable for detention under the Contagious Diseases Acts,; this caused her to jump into a dock. Catalogue reference: HO 144/78/A4010

On 15 March 1881, police officers Carley and Griffiths spotted a young woman in Snargate Street in Dover. They believed that she was behaving in such a way as to suggest she was a prostitute. They drew this conclusion after the woman had previously been seen in the company of soldiers and registered prostitutes in the town. 11

The police officers tried to approach the woman to ask for her address, but she fled at the sight of them. 12 This then gave way to a dramatic chase through the town’s streets. Eventually, in desperation, the young woman threw herself into the Granville Dock to avoid arrest by the police – only to be charged by the Borough Police with attempting to commit suicide. 13

The fact that this woman – later identified as Elizabeth Burley, aged 18 – went to such extremes to avoid questioning by police officers under the Contagious Diseases Acts, highlights the fear and shame that surrounded this legislation.

That Elizabeth B- should be driven in desperation, and that she should seek to escape from the open infamy involved by the attention of these officials, need not surprise anyone who has read anything of the ordeal to which the Acts compel women to submit. 14

After being pulled from the dock, Elizabeth was taken to the Sailors’ Home, where she was cared for while she recovered. As it turned out, Elizabeth Burley was not a prostitute. She had, however, recently fallen on hard times and had been made homeless two weeks before. 15 A previous resident of a local workhouse, Burley had a number of short-term contracts in service but was discharged for being ‘dirty and lazy’. 16 During the police investigation her ‘morality’ was repeatedly questioned and it came to light that she had ‘fallen [but] only in respect of one man, a Corporal in the army’. 17

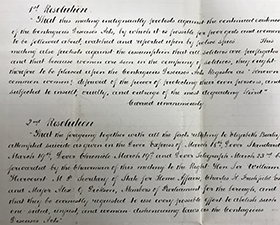

The dramatic events of 15 March and the subsequent investigation by police caused a public outcry. A number of meetings were held in Dover and a petition was sent to the government, expressing opposition to the acts and calling for their repeal following this case of mistaken identity. 18

Resolutions adopted at a public meeting, held as part of the outcry around Burley’s treatment. Catalogue reference: HO 144/78/A4010

The police had no legal right to accost (the girl Burley) in the public street; nor to run after her in the way they did; and that whether the girl was or was not immoral has nothing whatsoever to do with the illegal conduct of the police. 19

The two police officers who had ‘unjustly and illegally’ chased Elizabeth were ‘severely reprimanded’ and moved to different posts, and the case was eventually brought before Parliament. 20

Government officials also provided new guidelines for those policing under the Contagious Diseases Acts in Dover, as they didn’t want another public scandal like the ‘Burley girl’. 21

Newspaper article on the Burley case. Catalogue reference: HO 144/78/A4010

The Contagious Diseases Acts remained in place for a further five years before they were eventually repealed. For more than two decades, legislation had been in place which allowed for thousands of women to be questioned, forcibly examined and sent to ‘lock hospitals’. 22

While the repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts was undoubtedly a great victory for women such as Josephine Butler and Elizabeth Burley, as the 20th century would show, this was not the last time women would have to fight for rights over their own bodies.

Dr Claire Kennan is an AHRC Creative Economy Engagement Fellow based at The National Archives and Royal Holloway, University of London.

Notes:

- Admiral Edward Hawker, ‘A Statement of Certain Immoral Practices Prevailing in HM Navy’, in Judith R Walkowitz, ‘Prostitution and Victorian Society: Women, Class and the State’ (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980), p. 73. ↩

- Margaret Hamilton, ‘Opposition to the Contagious Diseases Acts, 1864-1886’, ‘Albion: A Quarterly journal Concerned with British Studies’, 10 (1973), pp 14-27 (p 14); Catherine Lee, ‘Prostitution and Victorian Society Revisited: The Contagious Diseases Acts in Kent’, ‘Women’s History Review’, 21 (2012), pp 301-16 (p 302). ↩

- Hamilton, p 14; Walkowitz, p 73 ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Walkowitz, pp 90-1. ↩

- In 1881, a report was compiled which highlighted the success of the Contagious Diseases Acts (see Catalogue Reference: HO 45/9511/17273A/188), and some medical practitioners actively endorsed the legislation (see Catalogue Reference: HO 45/9511/17273A/3. ↩

- Lee, p. 303. ↩

- Lee, p. 308; Annual Report of the Assistant Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police on the Operation of the Contagious Diseases Acts PP 1882 (291) LIII, pp. 9–13. ↩

- Lee, p. 307. ↩

- ‘CONTAGIOUS DISEASES ACT (WOMEN): Conduct of police in case at Dover’, Home Office file, 1881. Catalogue reference: HO 144/78/A4010/7. ↩

- Catalogue reference: HO 144/78/A4010/7, folio 1. ↩

- Catalogue reference: HO 144/78/A4010/4. This charge was subsequently dropped. ↩

- Catalogue reference: HO 144/78/A4010/3 ↩

- Catalogue reference: HO 144/78/A4010/4 ↩

- Catalogue reference: HO 144/78/A4010/7 ↩

- Catalogue references: HO 144/78/A4010/2, HO 144/78/A4010/7. ↩

- Catalogue reference: HO 144/78/A4010/3 ↩

- Catalogue reference: HO 144/78/A4010/14 ↩

- Catalogue reference: HO 144/78/A4010/4, 8 &14 ↩

- Catalogue reference: HO 45/9512/17273C/1 ↩

- Catalogue reference: HO 45/9511/17273A ↩

There is no such thing as an absolute right to our own bodies. Rights over our bodies is a slogan, a political slogan and I’d question it’s use in an article that’s about archives. If you want to write an opinion piece that’s one thing, if you want to write about history that’s fine too but when you present something about a primary source opinion and feeling needs to be left aside, especially slogans.

Of course there is such a thing as an absolute right to our own bodies. If you believe in the concept of private property, then ownership of one’s body is the simplest form of private property. If you believe that we should not have private property, then you must explain who is able to have ownership over our bodies other than us.

An explanation as to why you think this would be helpful. What isn’t helpful however, is complaining that the national archives included a statement that refers to an extrapolation of the human right to protection of property, under the false pretence that it is politicising history – this is political history, it’s inherently opinionated. Next time think before you spout some meninist nonsense – this is a secondary source, it is examining a feminist issue from a modern viewpoint, if you want to understand it from a perspective with no value judgements given to the past- just read the original acts.