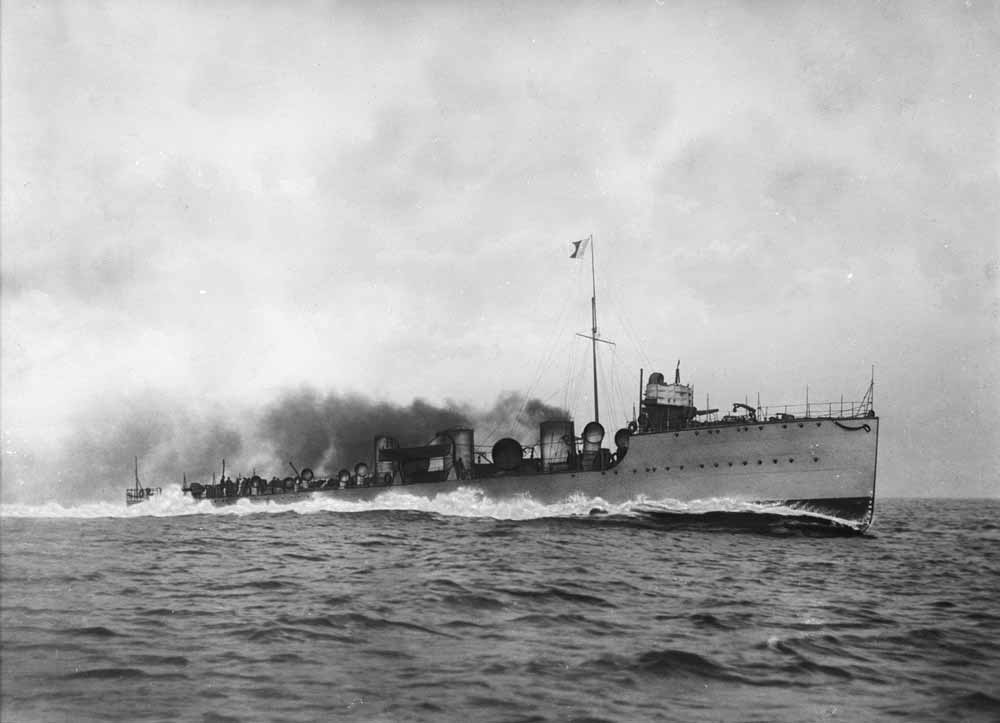

This month marks the centenary of the sinking of the Ghurka, a Tribal-class destroyer and part of 6th Destroyer Flotilla that served with the Dover Patrol.

HMS Ghurka at sea (Image: Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums, ref. 2931 War17)

The First World War was unquestionably the first truly global conflict, and campaigns at sea carried its effects to the most remote corners of the world. The sea battles that took place as far away as the Pacific and Indian Oceans were to reinforce the supremacy of the navy. Without control of the sea the vital resources and manpower required to prevail on the Home Front, Western Front and elsewhere would not have been available. This was reflected in Churchill’s debate in the House of Common back on 3 May 1901:

‘the whole course of our history, the geography of our country, all the evidences of the present situation proclaim beyond a doubt that Britain’s power and prosperity depend on the economic command of markets and the Navy’s command of the seas’

Trade blockades

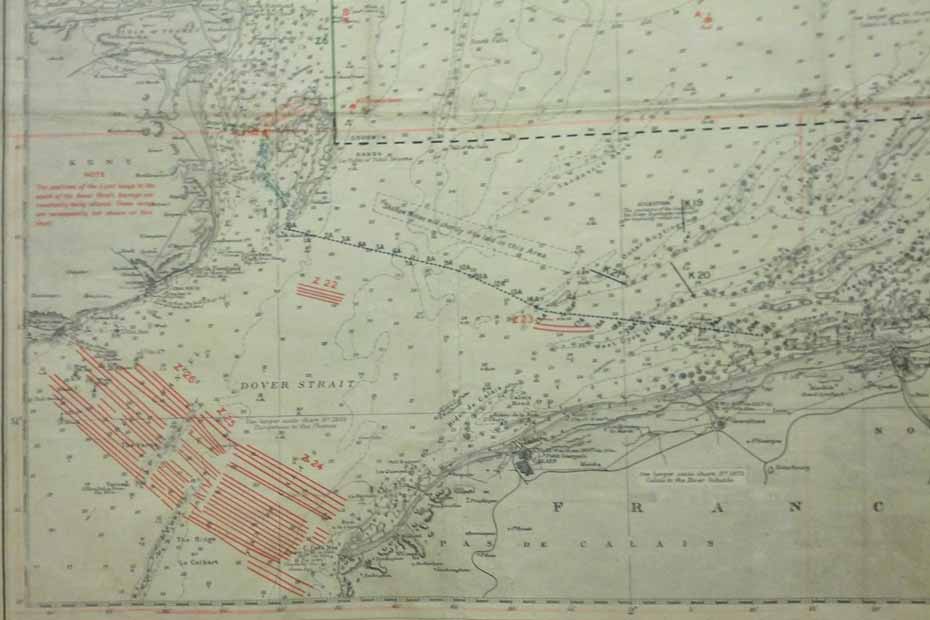

Trade blockades were an important element of the strategy adopted by British Naval policy makers and their allies at the outbreak of war in August 1914. The main objective of the policy was to restrict all overseas supplies of foodstuffs and articles of war to Germany and its allies. The Dover Patrol played an important role in covering the English Channel to prevent German shipping from passing through en route to the Atlantic.

Dover Patrol operations chart (catalogue reference: ADM 137/2115)

To counter this threat the Imperial German Navy introduced unrestricted submarine warfare in early 1915. However, the sinking of the Lusitania in May of the same year prompted U.S. President Woodrow Wilson to send an ultimatum to the German government demanding an end to German attacks against unarmed merchant ships. Aware of the danger of the U.S. joining the war, by September 1915 the German government had imposed constraints on submarine operations which almost suspended the U-boat campaign.

Though the Battle of Jutland in May 1916 was inconclusive, it showed that the Imperial German Navy was not strong enough to defeat the Royal Navy. This led the Germans to change their tactics and refocus on convert underwater operations, culminating in the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare on 1 February 1917.

This resulted in a surge in the Royal Navy’s losses. The heaviest losses from submarine attacks and mines were to torpedo boat destroyers, as this type of vessel was mainly deployed for anti-submarine operations: of 143 vessels lost in 1917-18, 41 were torpedo boat destroyers.

The Loss of HMS Ghurka

On 8 February 1917 the Ghurka, under the command of Lieutenant Harold G. Woolcombe-Boyce, struck a mine and sunk between Dungeness and the Royal Sovereign Light Vessel. At about 7.45pm, when the officers were about to sit down to their evening meal, a heavy explosion occurred at the forward part of the vessel. Commander Francis H. L. Lewin of HMS Attentive, who was visiting the Ghurka, said:

‘I found that the explosion appeared to have taken place in the vicinity of the foremost funnel. The upper deck in that vicinity was practically awash, the fore part of the vessels in that vicinity canting considerably in the air’ (ADM 137/3245)

Crew on the armed trawler Electra II saw the explosion; the Captain of the vessel, Lieutenant R.S. Bainbridge R.N.R., made an SOS signal and then rushed to give assistance. On arriving at the scene he managed to pick up Commander Lewin and four of the crew.

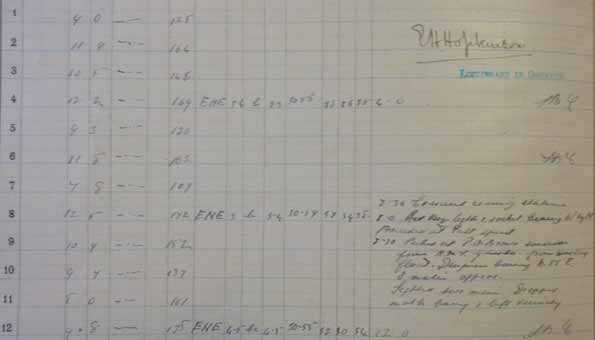

HMS P24’s log, Thursday 8 February 1917

Another ship on patrol in the vicinity was patrol boat P24, under command of Lieutenant E.H. Hopkinson. After seeing the signal from Electra II it came up at full speed and successfully rescued Petty Officer C.W.H. Brown.[ref]1. According to the Naval Staff Historical Monographs, which complied in 1933 in ADM 275/13 reported P24 as ‘seeing no survivors’.[/ref] However, according to the ship’s log, after picking up the Petty Officer and searching for other survivors the P24 sighted two more mines and left the vicinity (ADM 53/56291).

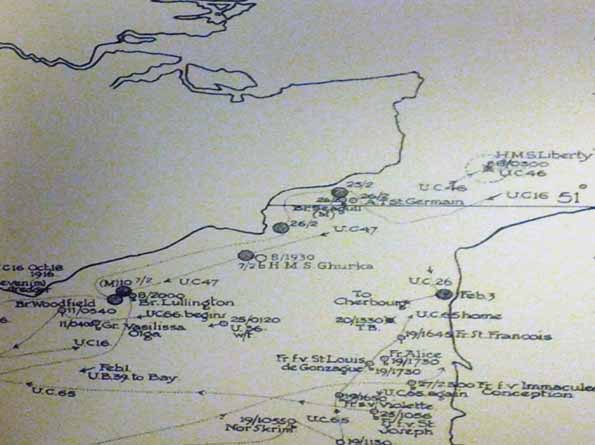

The line of operation of UC-47 (catalogue reference: ADM 275/13)

The submarine responsible for the sinking of the Ghurka was UC-47, a minelaying submarine commanded by Lieutenant P. Hundius, which started its first channel trip on 6 February. On 7 February eight mines were laid around Dungeness and the Royal Sovereign Light Vessel.

75 men were lost when the Ghurka sank, including Lieutenant Harold G. Woolcombe-Boyce. The wreck lies off Dungeness in 30m of water, with most of the crew’s remains still inside. In spite of this it was not officially designated a war grave until April 2008, and has been extensively professionally salvaged with explosives used in many places. Parts of the stern are still intact and stand 8m proud of the general wreckage.

My Great-Grand Uncle was one of the crew members lost, Leading Seaman William George Fortnum. He was the only one of his six siblings to not come to Canada (5fivewere British Home Children, the sixth came of her own volition). He was 28 when the ship went down, leaving behind his wife, Ruth (aged 27), and a child, William (aged 2).

Such a sad story

My great uncle was lost when the Ghurka sank in 1917 he was only 18 years old. Able seaman Alick Lincoln. Sadly we have no photo of him.

My great uncle William Savory, stoker, was lost when the ship went dow

My 2nd Cousin BENJAMIN WILLIAM JAMES HOOK (Stoker I Class) was lost when HMS “Ghurka” sank.