‘I have only been queer since I came to London… before then I knew nothing about it’

This surprisingly open expression of a queer identity and its link to London is found in a letter written in 1934 housed at The National Archives.

The author of the letter, Cyril Coeur de Leon, would have to wait a further 33 years before the passing of the 1967 Sexual Offences Act, which decriminalised homosexual acts between men in private in England and Wales. This year marks the 50th anniversary of the passing of the act, and the 60th anniversary of the Wolfenden Report, which recommended decriminalisation.

The National Archive’s documents reveal a surprising openness around sexuality in a time before homosexual acts were decriminalised. While it was never actually illegal to be gay the police criminalised certain social, cultural and religious practices. In the eyes of the law, meeting other men could be deemed as soliciting, and running a club could be seen as running a brothel or a disorderly house. In just going about their daily lives men could be arrested, prosecuted and imprisoned for up to ten years.

Despite this persistent targeting and surveillance, throughout the 1920s, 30s and 40s there was a thriving queer community who were able and willing to socialise despite the risk. A hidden network of private members clubs, pubs, restaurants and dancehalls provided a ‘safe space’ where men could meet other men regardless of the law.

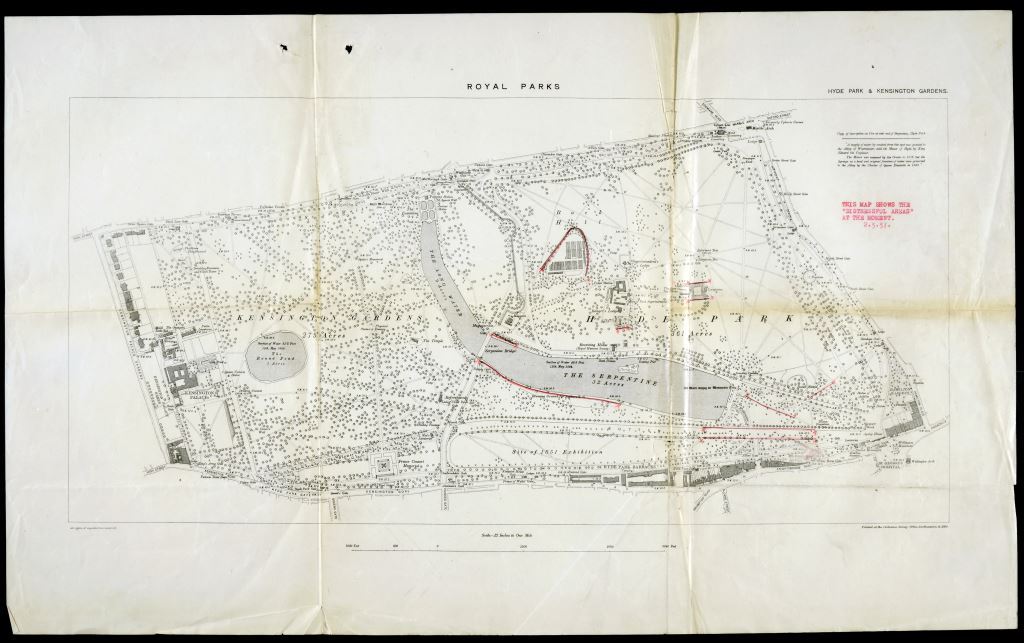

For many men in this era, the high entrance prices and lack of knowledge, meant private members clubs remained inaccessible. Instead they relied on outdoor and public spaces like urinals, known as cottages, and public parks, where there was far greater risk of being caught.

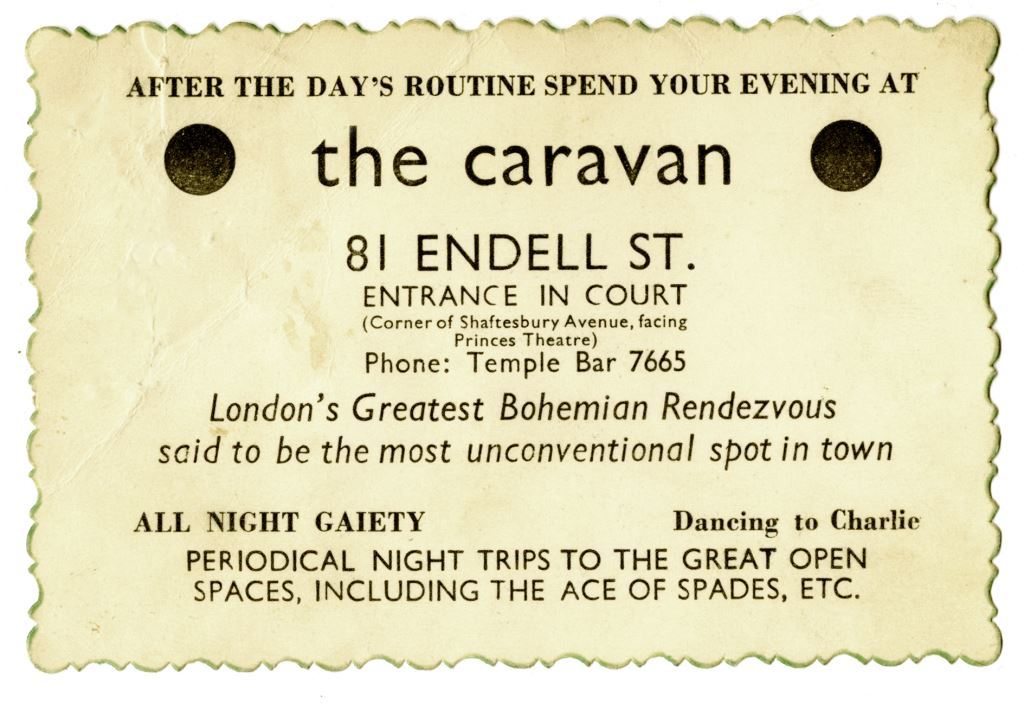

For others this widespread network of clubs and dancehalls were vital places where men could freely meet, socialise and undertake relationships with other men. One such club was the Caravan.

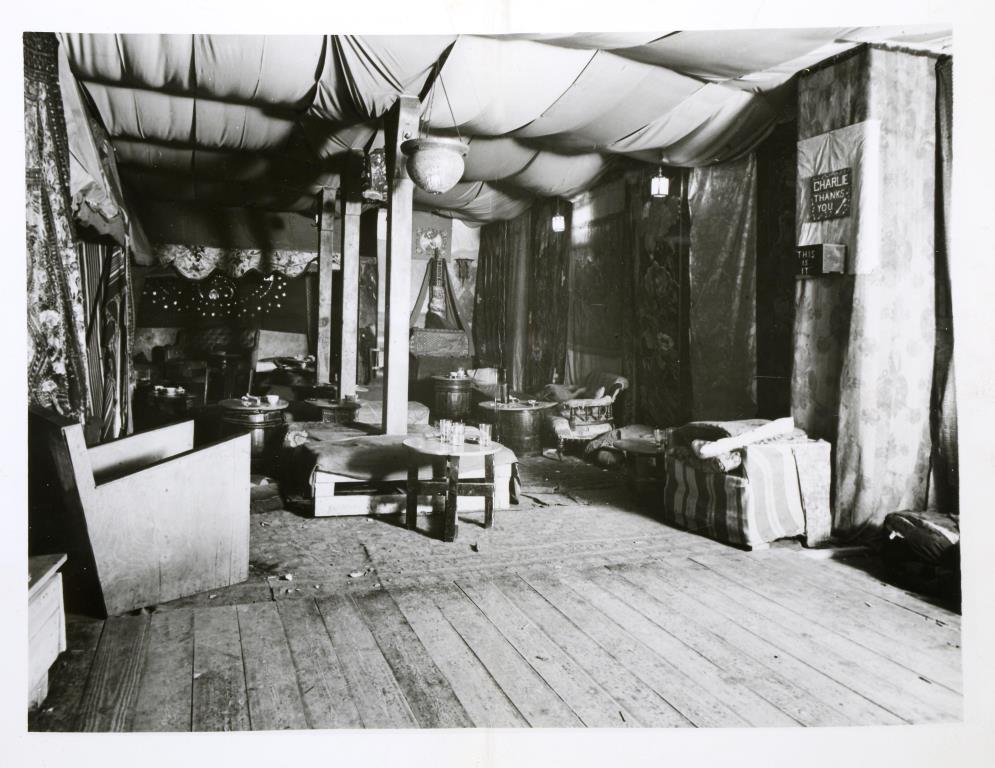

The Caravan Club, described in the 1930s as ‘London’s greatest bohemian rendezvous’, was a make-shift private members’ club in the basement of 81 Endell Street, Soho. It was owned by Jack Neave, known as ‘Iron foot Jack’ and William Reynolds known as Billy. For the price of 1 shilling for members, or 1s 6d on the door, ‘all-night gaiety’ could be enjoyed while dancing to the music of Charlie, the club’s accordion player.

Metropolitan police files indicate that soon after its opening in 1934, the Club was kept under regular surveillance due to a number of complaints about the manner in which it was run. A note, signed anonymously by ‘’Some rate payers of Endell Street’ describes the club as:

‘an absolute sink of iniquity… frequented by sexual perverts, lesbians and sodomites’ (MEPO 3/758)

In the early hours of the morning on 25 August 1934 a number of plain-clothed policemen entered the club pretending to be visitors. Divisional Detective Inspector Clarence Campion, the officer in charge of the raid, noted how he was able to introduce the officers without being noticed and described the scene that greeted him:

‘The small dance floor was crowded and the number was too large to allow dancing properly. Men were dancing with men and women with women, a number of couples were simply standing still, and I saw couples wriggling their posteriors, and where I saw men together they had their hands on the others buttocks and were pressing themselves together. In fact all the couples I saw were acting in a very obscene manner.’ (DPP 2/224)

Undercover investigation techniques were regularly adopted by the police to target clubs like the Caravan. These methods, particularly the use of agent provocateurs, led to growing public concern about the ‘moral corruption’ of the police officers taking part.

Campion’s report describes the dramatic moment when the police revealed themselves:

‘I waited until the officers had taken up their positions allotted to them, and I then had the music stopped and said to the assembly: “Police Officers are in this place to arrest principals for maintaining the place in a manner likely to corrupt morals, and you are all aiding and abetting, and if you will remain quiet you will be taken to the police station as quickly as possible.’ (DPP 2/224)

His statement ends with an account of Cyril de Leon approaching the inspector in an extraordinary act of resilience:

‘Well I don’t mind this beastly raid, but I would like to know if you can let me have one of your nice boys to come home with. I am really good.’ (DPP 2/224)

In the course of the raid 103 individuals, both men and women, were arrested and taken to Bow Street police station. During the arrest Cyril had to undergo the humiliating process of having his face tested for evidence of make-up with blotting paper.

The majority of individuals arrested, some labourers, shop assistants or waiters were found ‘not guilty’ on the condition that they never frequent such a club again, but the punishment for the owners was severe. Jack Neave and William Reynolds were found guilty of keeping a disorderly house described as ‘a place for people willing to pay for lewd, scandalous, bawdy and obscene performances and practices’. Neave was sentenced to 20 months hard labour in prison, and Reynolds received 12 months.

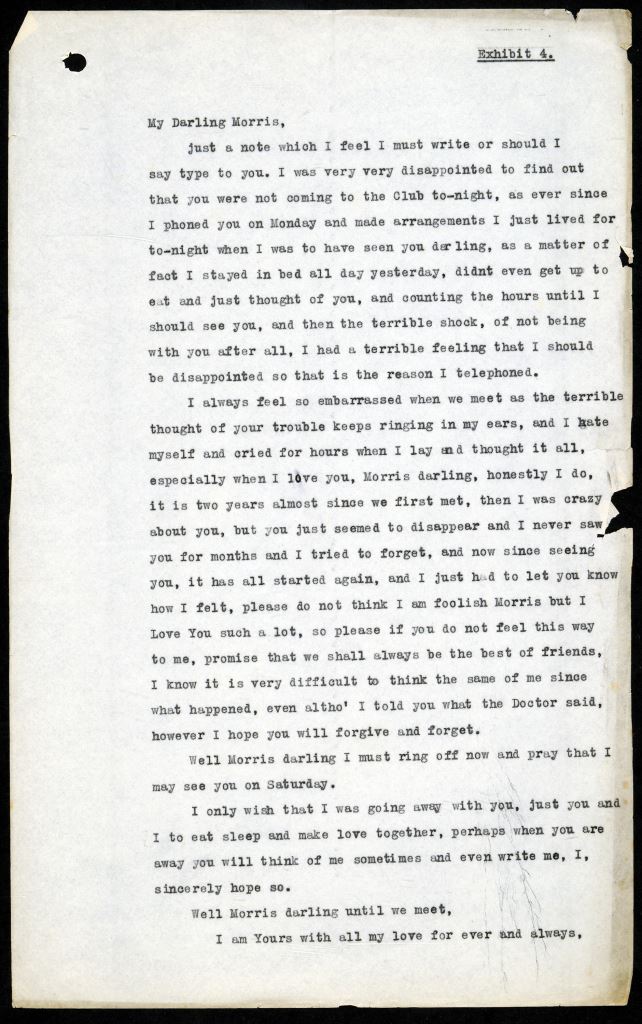

Among the police witness statements, reports and photographs of the raid and trial, there are personal letters that were used as evidence in court. These demonstrate a fascinating and unusual personal reflection on what it meant to be queer at the time.

The first letter, addressed from ‘Cyril’ to ‘My darling Morris’, was found at the scene. It begins, ‘I was very disappointed that you were not coming to the club tonight”, and describes ‘counting the hours until I could see you’. It signifies the importance of the Caravan Club as a space where ‘Cyril’ could be himself; somewhere not just for casual sex, but where same-sex relationships were forged. Found torn up under the divan with a powder puff, the note was retyped for the police file (DPP 2/224).

Another letter was found in a hotel bedroom on the Isle of Wight in the weeks following the raid. Written from Cyril to his dear friend Billy, the owner of the Caravan Club, the letter describes how he has ‘only been queer since coming to London two years ago’, and reveals he has a wife and a little girl. In addition to highlighting the social scene available to gay men in this era, it is revealing of ‘queer’ identity at this time.

The note ends with the powerful words, ‘Please be a dear boy and destroy this note’. Cyril was only too aware of the implications if it was found.