Today marks Holocaust Memorial Day – an annual national day, with events held across the country, which aims to commemorate the victims of the Holocaust and other genocides. It falls on the anniversary of the liberation of the most infamous Nazi death camp, Auschwitz, liberated on 27 January 1945 by Soviet soldiers. Each year, Holocaust Memorial Day (HMD) has a theme; this year’s theme is ‘how can life go on?’

Although I won’t answer the question how life can go on, I will outline how life did go on in the immediate post-war period for survivors of Nazi persecution. What happened to the millions of people liberated from camps and ghettos across Nazi-occupied Europe? Did they go back to their home countries? What was Britain’s role in helping survivors?

The situation in immediate post-war Europe

After liberation of the camps, the Allies faced huge challenges. The most immediate was how the sick and dying could be saved. Reports in the war diary of the 32nd Casualty Clearing Station, among the first units to enter Bergen-Belsen upon its liberation on 15 April 1945, estimated that 80% of the predicted 60,000 former inmates required hospitalisation. Lieutenant Colonel Johnston reported that 500 people were treated every day due to severe malnutrition, typhus, dysentery and diarrhoea (WO177/669).

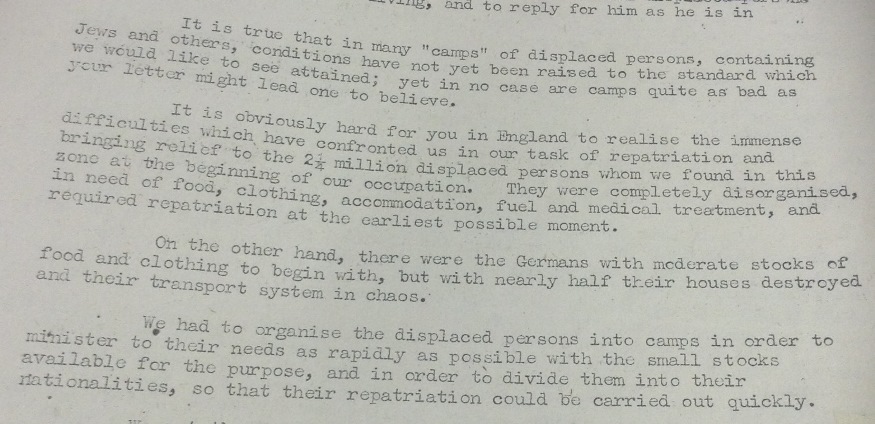

Another challenge was the huge and complex task of repatriation. There were millions of Displaced Persons (DPs) and refugees in Europe in the immediate post-war period. In October 1945 – after repatriation had begun – Major General Templer of the Control Commission for Germany wrote to Lady Reading, who had expressed concern about the conditions of Jewish DPs in the British Zone, that:

‘it was obviously hard for you in England to realise the immense difficulties confronted in the task of repatriating and bringing relief to 2 ¼ million displaced persons in the British Zone.’ (FO 1049/81)

Letter from Major General Templer to Lady Reading in response to her letter of concern about living conditions of Jewish DPs, 26 October 1945 (catalogue reference: FO 1049/81)

Although an exaggerated number – Foreign Office estimates (FO 945/362) report that there were 531,000 DPs in the British Zone in December 1945 – the scale of the task facing the British government was immense. Repatriation and encouraging DPs to return to their home country, favoured by the British, was one task; for Jewish DPs who had, in many cases, no families, homes or possessions to return to, resettlement became the priority.

Displaced Persons camps

To ensure that measures for repatriation in particular could be established as quickly as possible, the British Military – as described in the letter by Major General Templer – had to:

‘organise the displaced persons into camps in order to minister their needs as rapidly as possible with the small stocks available for the purpose, and in order to divide them into their nationalities, so that their repatriation could be carried out quickly.’

Many former concentration camp inmates therefore found that their first months, and sometimes years, of liberation were spent on territory where they themselves had not only suffered at the hands of their Nazi captors, but often where many members of their family had perished. Belsen became the temporary home to an estimated 11,000 Jewish DPs, the only camp exclusively for Jewish refugees and DPs.

In his letter, Major General Templer revealed to Lady Reading that the British and United Nations Relief and Administration (UNRRA) – an international body that provided financial assistance for repatriating DPs as well as clothes, food and medical services, and helped the military run the camps – tried to return a sense of normality to the remaining DPs. They were offered education and vocational training to prepare them for new jobs elsewhere, and nurseries and crèches for children were provided. To improve morale, there were generous weekly rations of cigarettes ‘greater than that of British troops’ and there was a vast array of entertainment including dances, concerts and films (FO 1052/501).

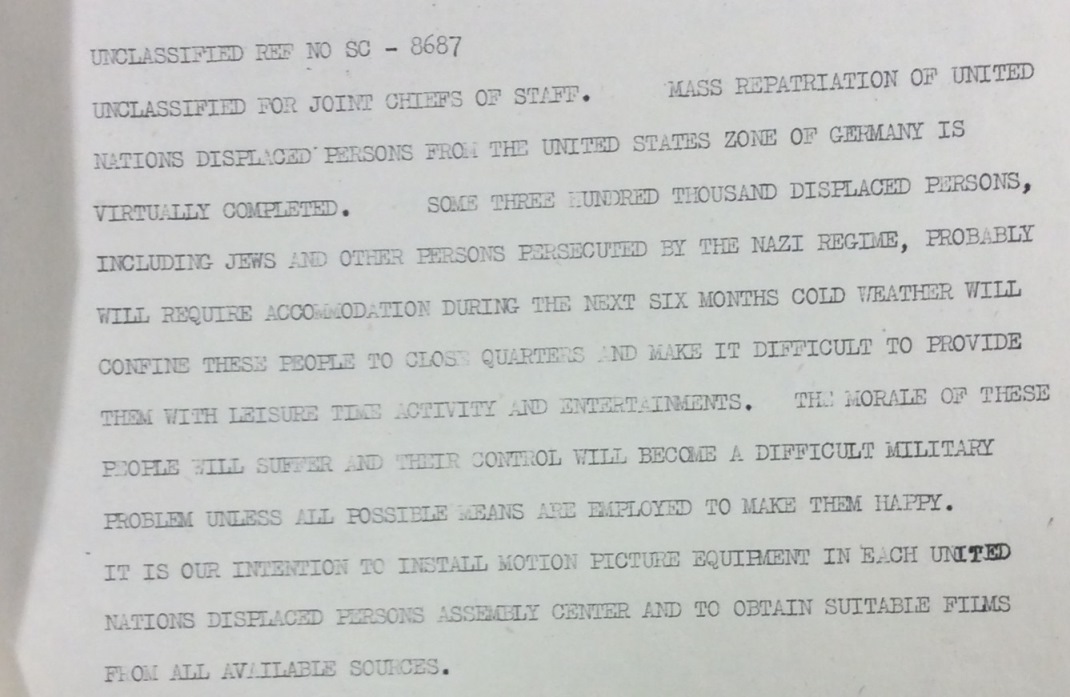

Discussions over the welfare of DPs and how to improve morale, October 1945 (catalogue reference: FO 945/695)

The hundreds of assembly centres and camps across Germany, Austria and Italy were, of course, temporary, though it wasn’t until 1952 that Wentorf, the last of the DP camps in the British Zone, finally closed (FO 1060/666). Figures sent to the Foreign Office show that 154,996 Jewish DPs were also still receiving UNRRA assistance in 1947, before it disbanded in 1948 (FO 371/61956). Repatriation and resettlement of DPs and refugees was a more difficult task than initially imagined.

Repatriation and resettlement

Although the focus was on encouraging DPs to return to their country of origin, a pressing concern for the British government was where to resettle those who refused repatriation. Many Jewish DPs, particularly Poles, Hungarians and Romanians, were unable or unwilling to go home. This was often because their citizenship had been revoked by the Nazis, rendering them stateless; anti-Semitism was still rife in their countries of origin; or, as one representative of the Jewish Congress stated in 1945, ‘we will not be driven back to the lands which have become the mass graveyards of our people’ (FO 1049/81). Many non-Jewish DPs, particularly Poles (who formed the majority of the DPs in the British Zone), also refused to return home. In addition, there was a continual flow of new arrivals who fled from the east to the west to avoid persecution from the Communist regime.

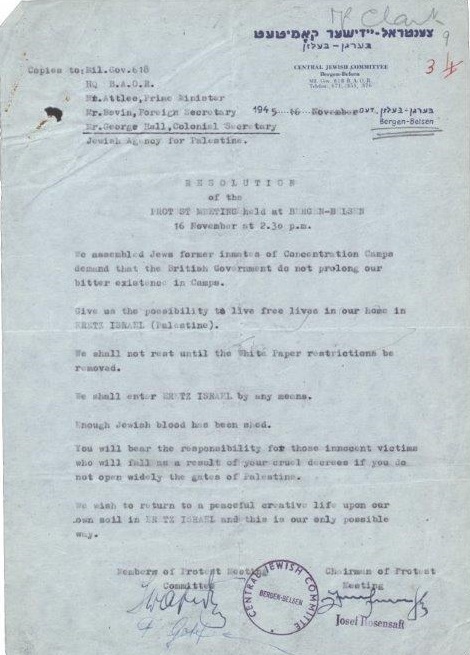

The resolution of the meeting held at Bergen-Belsen in protest against restrictions on entering Palestine, 16 November 1945 (catalogue reference: CO 733/455/6)

The preferred option for these DPs was Western Europe and, for Jewish DPs, Palestine. In November 1945, representatives of the Jewish Congress met at Belsen on behalf of all former Jewish inmates of concentration camps in protest against the restrictions on entering Palestine. They appealed to the British to free them from the ‘bitter existence in camps’ and to ‘open widely the gates of Palestine’ (CO 733/455/6).

Initially the British government limited numbers entering Palestine. Nonetheless, by 1947 it had accepted over 300,000 persons into the UK and under the European Volunteer Workers scheme planned to accept a further 100,000 (FO 371/61956; LAB 9/191). This scheme aimed to recruit single men and women from DP camps to meet the demand for labour in key occupations such as industry and farming. Britain, they argued, had the ‘most successful scheme’ in allowing ‘more than a quarter of all refugees in Europe…the chance to start a new life.’

Even with the chance of a new life, the trauma and effects of the Holocaust and Nazi persecution left a permanent scar on survivors; their lives had altered irreversibly. But the re-establishment of a ‘normal’ life was of utmost importance. Marriages and births within the DP camps peaked and the years 1946 to 1947 saw a Jewish ‘baby-boom’ in occupied Germany.[ref]1. Anita Grossman, ‘Victims, villains and survivors: Gendered perceptions and self-perceptions of Jewish Displaced Persons in occupied post-war Germany’, Journal of the History of Sexuality, 11 (2002), 302[/ref]

Britain too played its part in allowing approximately 400,000 refugees and DPs into the United Kingdom, some of whom stayed permanently, got married, had children and made a new life for themselves. It was making a new life for themselves which was, perhaps, the best way to counteract the attempts of the Nazis to wipe out their friends, families, neighbours and religion. Their lives, unlike so many millions of others, fortunately could and did go on.

Quite a few people settled in the United Kingdom especially because they didn’t want to return to their country of origin because of the Communist regimes in Eastern Europe at the end of the war and there was no compensation to resettle. The records in series FO 950 (including those without names) show how other nationalities like Dutch people did return home. Eva Schloss’s book (“After Auschwitz”) is a book I would recommend.

hi David, i am trying to track one of my relatives, could you please get in touch with me? thank you inna

Hi Inna,

If you’d like to get in touch with our record experts, go to our ‘contact us’ page at http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact/ for details on how to contact them through email or live chat.

Best of luck with your research.

Kind regards,

Liz.

[…] techadmin on January 27, 2017 What happened to refugees and Displaced Persons after the Holocaust?2017-01-27T10:06:08+00:00 – Journals & Publications – No […]

It is important to touch on this issue since the holocaust was a great massacre of people, especially one whose aim is to exterminate a social group based on race, religion or politics.

I was born In a dp camp in Kassel en minchenburg. Can I trace what year the dp camp was ongoing. 1949 was year I was born.

If you can reply I would appreciate it,

Linda

Dear Linda,

We may have records relating to your enquiry: the way to find out is to try searching for document references in our online catalogue. Before you try a search I suggest you consult our research guide on records relating to Refugees: http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/refugees/.

Our guides provide advice on the records we hold and how you can search for them using the catalogue. You can search our catalogue using keywords and dates to see what is held here and at over 2,500 other archives across the UK. For advice on searching effectively, read Discovery help: http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/discovery-help/

We can’t answer research requests on the blog, but if you go to our ‘contact us’ page at http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact/ you’ll see how to get in touch with our record experts by email or live chat.

Kind regards,

Liz.

Due to the context of the last paragraph of this otherwise admirable summary, some might interpret it as meaning that Jewish Holocaust survivors were heavily represented among the 400,000 refugees and DPs admitted to Britain, which is not the case as i understand it, including under the European Volunteer Workers Scheme. The work by scholars in this field Tony Kushner, Louise London etc surely suggests otherwise and that Jewish survivors did not obtain entry to the UK in any large numbers after the war. I appreciate that most of the focus on Britain’s role in this period vis a vis Jewish DPs related to passage to Palestine, but I’d be very interested in any NA material relating to policy on Jewish DPs’ admission to –or exclusion from–the UK berween 1945 and 1948 and indeed about DPs who wished to go to the UK or the US rather than Palestine, even if only a minority.

What about thousands of refugees who had already fled to the UK in 1940 – where were they located in the UK and when were they returned to their respective countries?

All fascinating but you fail to mention the first holocaust of the 20th century… the one from which Britain drew inspiration and which inspired in Germany on how to conduct genocide. That was the genocidal holocaust the British conducted against the Boer Republics in the Boer War. The war that saw the introduction of concentration camps, displacement, starvation, property destruction and scorched earth….. all honed by the British as they systematically raped the Boer nations, starved them and allowed the women and children to die of disease and neglect while they transported the men 1,000’s of miles, not allowing them to return.. Hitler owed the British a vote of thanks… as did Stalin….. for showing them how to conduct a good and merciless holocaust.

I’ve only just read Don Macintyre’s comment and, like him, having read Tony Kushner, wonder at the motives of the British authorities in their preference for Polish workers rather than Jewish DPs. There is another issue here, too: how were the preferences of the Jewish DPs ascertained?

“You will bear the responsibility for those innocent victims who will fall as a result of your cruel decrees if you do not open widely the gates of Palestine.” Central Jewish Committee letter 16 Nov 1945 (above)

What an extraordinary document. A terrorist threat to modern ears, and therefore probably not representative of the character, hopes and aspirations of the majority of the Jewish DPs. But unsurprising in the light of the Zionist insurgency and St. David Hotel bombing of the British Mandate government in Jerusalem by Irgun just 8 months later. Do we know what the immediate reaction of the Atlee government was, I wonder?