This blog contains spoilers for BBC One’s ‘Gunpowder’ series.

One of the most satisfying parts of BBC One’s ‘Gunpowder’ series is seeing the critical role that letters play in the discovery, and manipulation, of the plot by government officials. Letters were an insecure medium in this period as they were conveyed to the recipient by a servant, a paid carrier, or a friendly contact willing to deliver the letter. They could easily be intercepted and tampered with. In ‘Gunpowder’ we see how Robert Cecil, Earl of Salisbury, exploits these possibilities to discover the plot: he intercepts and decodes correspondence written in invisible ink concerning the negotiations of the peace treaty with Spain; later he creates and plants the letter to Lord Monteagle that leads to the discovery of the plot.

Although the Monteagle letter is given a fictional back-story in this series, the producers have taken care to ensure that the appearance and content of the letter are authentic (see an image of this letter here); many of the covert tactics depicted in the series were really used in the period and evidence for these can be found our collection.

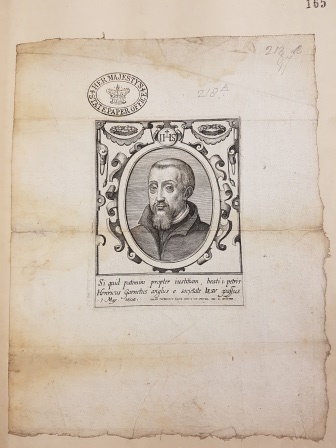

Henry Garnett, State Papers 14/216/2 item 218A

We hold hundreds of letters and documents relating to the Gunpowder Plot. These include a sequence of letters to and from the Jesuit priest, Henry Garnett, that demonstrate a type of clandestine communication often used by the Catholic underground – letters written in orange juice. The orange juice acts as invisible ink: it fades on drying, and only becomes visible once the paper is warmed. Garnett used this technique to communicate with his friends and associates while he was imprisoned in the Tower of London; as the orange juice remained visible after it had been warmed it would indicate whether or not the letter had been intercepted and read.

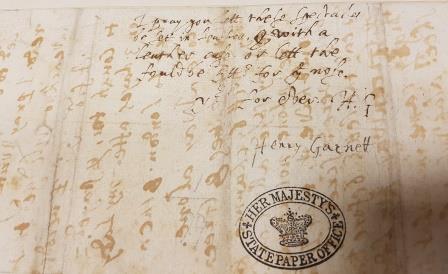

The first letter in the sequence is much smaller than a usual letter and was evidently wrapped around a pair of glasses with a request in normal ink to ‘lett these spectacles be set in leather…’. From the image below you can make out the faded orange juice text on the reverse of the paper. Here Garnett was able to write his secret message concerning previous correspondence and what he has revealed to his interrogators, as well as snippets of information about his visitors: ‘My Lady Digby came in. What did she? Alas but cry’.

Henry Garnett to Thomas Garnett, SP 14/216/2 item 241

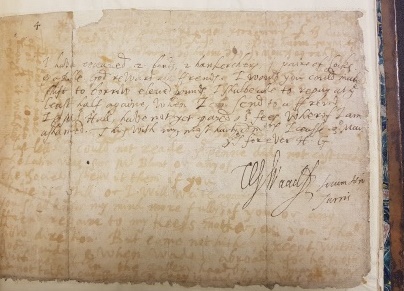

The next letter in the sequence, to Ambrose Rookwood – alias Thomas Sayer, one of the Gunpowder Plot conspirators – is written in a different form. The secret writing appears in four blocks of text, including one section written on the reverse of the visible lines. Once again it concerns the difficulties of communicating in such a complex manner: ‘Your last letter I could not reade’. Garnett also revealed tensions between him and the leader of the conspirators, Robert Catesby:

‘Master Catesby did me much wrong and hath confessed that he tould them that he said he asked me a question in Q[ueen] Elizabeth’s time of the powder action and that I said it was lawfull. All which is most untrew. He did it to draw in others. I see no advantage they have against me for the powder action’.

He also asks ‘if we have any mony of the society I wish beds for James John and Harry who all have been often tortured’.

Henry Garnett to Ambrose Rookwood alias Thomas Sayer, SP 14/216/2 item 242

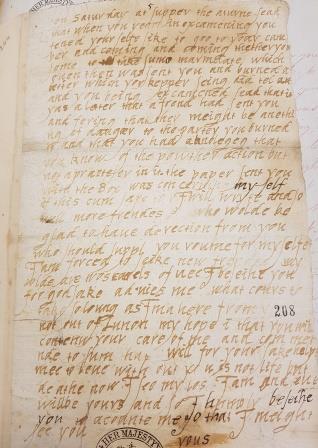

Garnett also corresponded with Anne Vaux, who had sheltered and protected him and other Jesuit priests. Again, Garnett used orange juice to conceal the content of his message, with varying degrees of success. Anne was clearly distraught at Garnett’s capture, and she wrote: ‘My hope is that you will continew your care of me and commend to sum that will for your sake helpe me to leve without you. Is not life but death now. I see my los. I am and ever will be yours ….’ The intensity of Anne’s relationship of Garnett has often been commented on, and is given an added poignancy when rendered in such desperate form.

Anne Vaux to Henry Garnett, State Papers 14/216/2 item 244

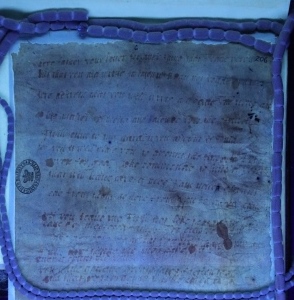

Another letter is barely legible, but seems to refer to an attempt she made to see Garnett from the gardens below the tower. Even when photographed under ultraviolet light, the text of the letter is still extremely difficult to read – but I welcome any suggestions!

Anne Vaux to Henry Garnett, State Papers 14/216/2 item 243

The irony of the care taken over this secret correspondence was that Garnett’s cover was already blown: the letters were being passed by his gaoler to the investigators of the plot and the orange juice deceit was easily discovered. But Garnett’s keepers needed a confession, and so they sought to entrap him and discover further information by carefully copying the letters – orange juice ink and all – and forwarding them to the intended recipient.

Garnett eventually confessed and was executed; Anne was interrogated but released, and continued to play an important role in the underground Catholic network. The letters were filed as part of the investigations, where their very material nature – from the use of invisible ink to their disguise as a wrapper for a pair of glasses – gives a real sense of the desperation and drama of the plot.

Further reading

- ‘God’s Traitors: Terror and Faith in Elizabethan England’ by Jessie Childs

- ‘Gunpowder: The Players behind the Plot’ by James Travers

- ‘The Material Letter in Early Modern England’ by James Daybell

There was always at the back, the memory that Pope Pius V had excommunicated Elizabeth 1, and called her the ‘pretended queen’ – absolving all her subjects from allegiance to her – which made all ‘Catholic’ subjects a potential traitor for ever! Robert Hutchinson, ‘House of Treason, the rise and Fall of a Tudor Dynasty’ page 228, Phoenix books. Politics as usual!

Love the Fawkes material.

I am a post grad history student and am interested in plots generally. As a mature self isolating individual i along with many others am finding it difficult to travel but would welcome the opportunity to converse via email with anyone else interested in plots successful or not.

I’ve done a little work on transcriptions of wills and testaments and agree that this is probably one of the more difficult jobs we give ourselves. I’d just like to thank you for taking this job on