News from Venice, 15 January 1667:

‘..and the building up of the new town is going on with all speed, and all beauty.’ 1 (SP 120/8)

That the Great Fire of London occurred in the sixth year of Charles II’s reign (2-5 September 1666), destroying St Paul’s Cathedral and most of the central area of the capital city, is well known. According to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, around 87 churches were burnt and so were 13,200 houses, leaving between 65,000 and 80,000 Londoners homeless. 2

This dramatic occurrence, which may have contributed to the end of the plague (the other major tragedy experienced by the city the year before), has been much studied by historians, primarily to reconstruct the history of an event in itself crucial for understanding early modern London.

Less known, and yet fascinating, is that The National Archives holds some early modern foreign pamphlets and gazettes, the analysis of which can illuminate the transmission, diffusion and reception of English news on the continent, such as that of the Great Fire. The verbal image of a burning London reached many people in many countries.

I recently had the good fortune to work at The National Archives on a placement as part of my PhD studies with the White Rose Network at the University of York. During my time here, while learning from the expertise of the medieval and early modern team, I took a look at various international accounts of the Great Fire and found these were particularly informative in the Venice and Genoa gazettes. I focused on those printed in the immediate days after the disaster and those printed in the following six months or so. Unlike England, most of Europe and certainly all the Italian states had adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1582, so a difference of ten days must be remembered when looking for news abroad.

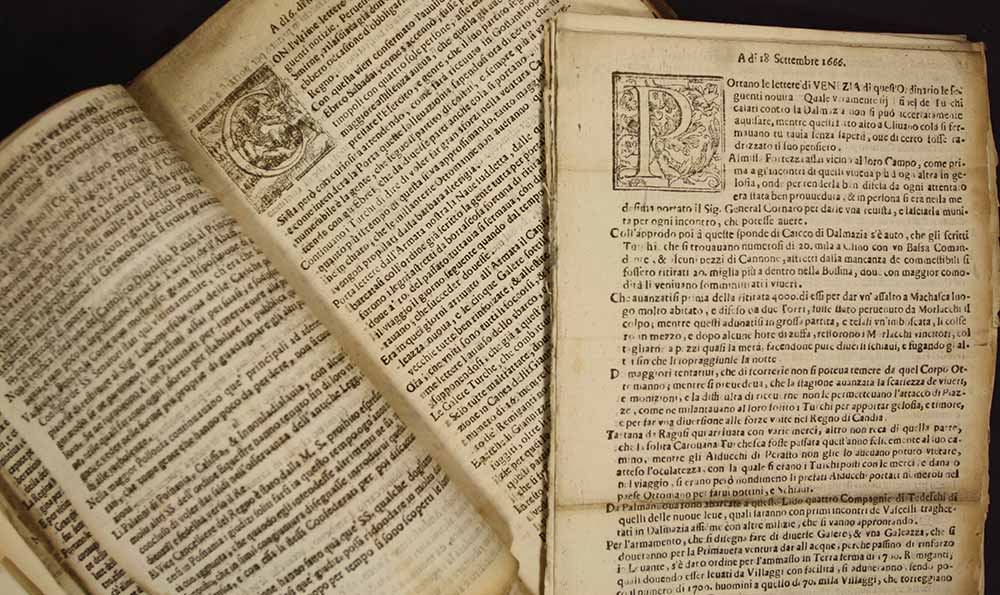

Italian gazettes held in the State Papers at The National Archives

Overall, it is easy to see that the Great Fire was not only understood as ‘breaking news’ (making a parallel with our times), it was also matter of a more persistent interest, populating gazettes and pamphlets for a long time. It soon became an essential element of the history of the city and its inhabitants narrated abroad.

As the opening quotation proves, the state of London and its rebuilding was still discussed five months after Great Fire; significantly, moreover, it was also recalled in order to furnish some contextualisation, some setting, of news completely different in nature. For instance, on that same Venetian page dated 15 January 1567, we can read that ‘the rebels of England, not yet well mortified by pestilence, war, by many fires and many floodings, still proudly rose up…’. 3 (SP 120/8).

The weeks just after the event were those in which the Great Fire was most narrated and described. On 18 September, the Venetian gazette wrote that:

From the letters from England, and from Holland, little can be said in more depth since they all aim to to discuss the elapsed fire; given that of the same fire a perfect report has been printed, anyone who wants to fully satisfy his knowledge, can resort to this said report. 4 (SP 120/9)

From a news item like this we clearly get a sense of the resonance given to the Great Fire. Unlike other news, the Italian reader was provided with nothing less than a separate description of the event – a description allegedly ‘perfect’, that here means ‘complete in its entirety’.

Extract from Venice gazette, 27 November 1666 (catalogue reference: SP 120/9)

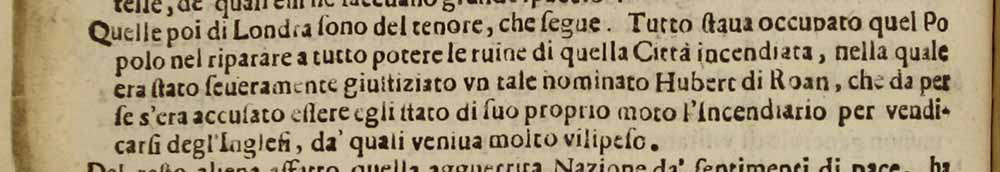

It is a true pity that The National Archives does not hold a copy of the above quoted report; however, we can grasp what it would have likely said from other news dated at Venice, 27 November 1666, and Genoa, 20 November:

‘The news from London is of the following content. The entire population was occupied in repairing, with all their strength, the ruins of that burnt city, in which a certain Hubert of Roan was executed since he had accused himself spontaneously to have been the arsonist, in order to get revenge over the English by whom he was very much offended.’ 5 (SP 120/9)

‘The letters from London of 23rd (October) say that the universal fasting was solemnly celebrated there on 13th, which His Majesty had ordered due to the fire of that City.’ 6 (SP 120/1)

Two other very significant pieces of news appeared on 6 November 1666, one after another.

Extract from Venice gazette, 6 November 1666 (catalogue reference: SP 120/8)

Their translation is as follows:

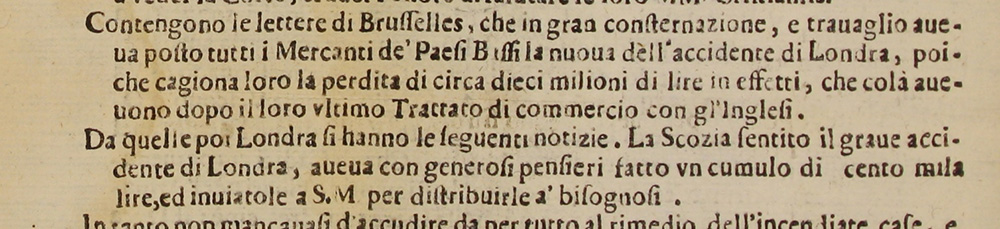

‘The letters from Brussels say that the news of the accident in London put all the merchants of the Netherlands in great consternation and labour, because it caused them the loss of around 10 million lire worth of goods, which they had from their last treaty of trade with the English there.

From those of London then we have the following news. Scotland, having heard about the serious accident in London, had gathered with free donations a sum of 100,000 lire, and sent it to His Majesty to distribute amongst the people in need. 7(SP 120/8)

News like that of the Great Fire was obviously international news, which soon moved from England to the continent and which described the event, precisely like news nowadays does, from different angles. As well as reporting on the solemn fasting, the Scottish donation, and the strength of the Londoners rebuilding their city, there was also a clear attention toward the economic repercussions and meaning of such a tragedy.

350 years after the fire, thanks to the holdings of The National Archives we can still study this spectacular and major event of the history of London, of its inhabitants, of the news which connected London with people far away who only got to know about the fire via the printed press.

Notes:

- 1. ‘…e la fabbrica della nuova Città si va tirando avanti con ogni celerità, e con ogni bellezza.’ ↩

- 2. Stephen Porter, ‘The Great Fire of London’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. ↩

- 3. ‘… i ribelli d’Inghilterra, non ancora bene mortificati dalla peste, dalla Guerra, da tanti incendij e tante innondazioni ancora orgogliosi insorgevano…’ ↩

- 4. ‘Delle lettere d’Inghilterra, e d’Olanda poco si può raggualgiare, mercè che essendo tutte rivolte a discorrer del trascorso Incendio, ed essendosene del medesimo fatta stampata una perfetta Relazione, a quella potrà ricorrere, chi brama appieno satisfarli.’ ↩

- 5. ‘Quelle poi di Londra sono del tenore che segue. Tutto stava occupato quel popolo nel riparare a tutto potere le ruine di quella città incendiata, nella quale era stato severamente giustiziato un tale nominato Hubert di Roan, che da per se s’era accusato essere egli stato di suo proprio moto l’incendiario per vendicarsi degli Inglesi, da quali veniva molto viliperato.’ ↩

- 6. ‘Portano le lettere di Londra del 23. caduto, come alli 13 si fosse celebrato solennemente il digiuno universal, che S.M.B. haveva ordinato a cagione dell’incendio di quella Città.’ ↩

- 7. ‘Contengono le lettere di Brusselles, che in gran costernazione, e travaglio aveva posto tutti i Mercanti de’ Paesi Bassi la nuova dell’accidente di Londra, poiche cagiona loro la perdita di circa 10 milioni di lire in effetti, che cola’avevono dopo il loro ultimo Trattato di commercio con gl’Inglesi. Da quelle poi Londra si hanno le seguenti notizie. La Scozia sentito il grave accidente di Londra, aveva con generosi pensieri fatto un cumulo di cento mila lire, e inviatole a S.M per distribuirle à bisognosi.’ ↩

[…] techadmin on September 2, 2016 The Great Fire of London viewed from abroad2016-09-02T08:30:53+00:00 – Journals & Publications – No […]

Do you mean Robert Hubert from Rouen in Normandy, France, when you talk about Hubert of Roan. The evidence, is I understand, that he was innocent as his claims that the fire was in Westminster (and outside the City of London) were false as we know the fire did not reach Westminster, which is someway outside the City of London’s boundaries. The Great Fire destroyed many of the homes from which people could almost reach out and touch the house on the other side of the street and led to the Great Plague of 1665 and its easy passage across London and the sanitary conditions became better but until sewers were built it didn’t eradicate the problem. Given that London didn’t have a fire service at the time there was little that could be done, but I believe is that unrefined flour may have caused the fire and some people believed ‘foreigners’ started the fire but that seems unlikely. As with all newspaper articles they should be just one source as they could be biased or mistaken in the information, personally I doubt that everyone in London helped rebuild London, not least because the plans for rebuilding London on a boulevard system like in Paris were rejected.

[…] Cover: picture of an Italian gazette, held in the State Papers at The National Archives, in an article about the fire. More info here. […]