Over the last few months I have introduced some of the convicts we have uncovered in our cataloguing of record series HO 17 (criminal petitions for mercy 1819-1839). The detailed correspondence pleading mitigating factors like unemployment, ill health, youth, age or perhaps providing witness statements and other evidence can provide unexpected insights into early nineteenth-century life. The case of George Sanglier, the workhouse master who featured in last month’s blog, provides a first hand account of the power relations within the Poor Law system, for its employees and the paupers who were unfortunate enough to rely on its relief.

In this blog I will introduce some petitions which include complaints from convicts about the conditions in which they were kept. Their detailed complaints about prisons and prison hulks provide fascinating and unsettling insights into what it was like to be on the receiving end of 19th century justice.

Life aboard convict hulks

In 1826 convict Henry Adams made a series of allegations and complaints about his treatment on the York and the Antelope convict hulks (catalogue reference: HO 17/49/125). Adams wrote that ‘Convict Hulks are totally forgotten Places teeming with every Crime that can degenerate a Man’. Convict hulks were huge floating prisons moored off the coast of England (the York was moored at Gosport, in Hampshire) and overseas in territories like Bermuda (where the Antelope was stationed). Adams claimed that he was kept in double leg irons on the York, and that John Henry Capper, Superintendent of Convicts, read all of his letters for fear that Adams would expose the cruelties of hulk life.

Adams also claimed that he has been singled out for harsh treatment because he had written to Capper about conditions on the Antelope: ‘Officers were Acting like Drunken Savages, the Antelope was literally speaking a floating Hell. This government knows and wish to suppress [the facts]’. He stated that the officers on the Antelope assaulted him when they found out about his complaints and he had fought back, for which he was sent back to England for trial and held on the York.

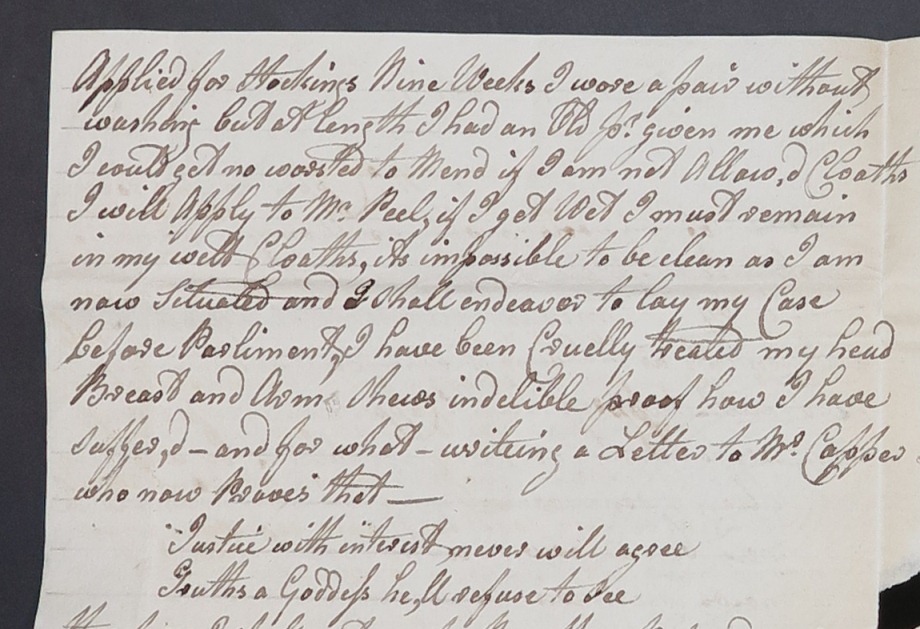

Writing about the York, he complains about the cold. When he applied for a blanket he was given a small old one, and when he applied for stockings he had to wait over two months: ‘nine weeks I wore a pair without washing but at length I had an old pair given me which I could get no worsted to mend… if I get wet I must remain in my wett cloaths, its impossible to be clean as I am now situated’. He had no tools to do the work expected of him and ‘what rations I get is shamefully small’.

The Home Office investigated Adams’ allegations and with his papers we find a letter from the overseer of the York hulk, Alexander Lamb, stating that Adams is treated the same as the other convicts. His letter paints a picture of daily life on the hulk:

‘His slops have been issued to him in the usual manner, bearing in mind that no new slops are issued so long as any second hand ones remain in store. He receives 3 ¼ oz of biscuit, three days in the week, the other three one half-penny worth of tobacco and a pint of small beer daily as a ration from the Ordnance. He is at present employed in the carpenter’s shop at the Gun Wharf, where he makes himself useful and is attentive, ‘tho his language is violent, and I certainly consider him a most mischievous and dangerous character.’

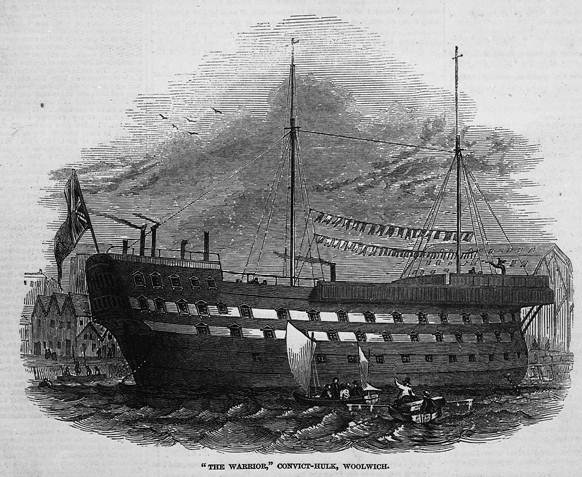

We can gain more of an insight into life on the hulks from another convict, William Burgess. In 1824 Burgess wrote to the Home Office to complain about the brutal punishment meted out to him on the Justitia convict hulk, which was moored at Woolwich (catalogue reference: HO 17/62/46). His allegations centred on an overseer, Captain Smith, who he said treated him ‘in a cruel and oppressive manner unbecoming the Character of an officer and Gentleman’. During the day working parties of convicts left the hulks to work on land or in the dockyards, doing things like laying roads, carpentry, construction work and other forms of heavy labour. Burgess could not complete the labour required of him owing to his ‘ill state of health and having a bad rupture’ and described his punishment:

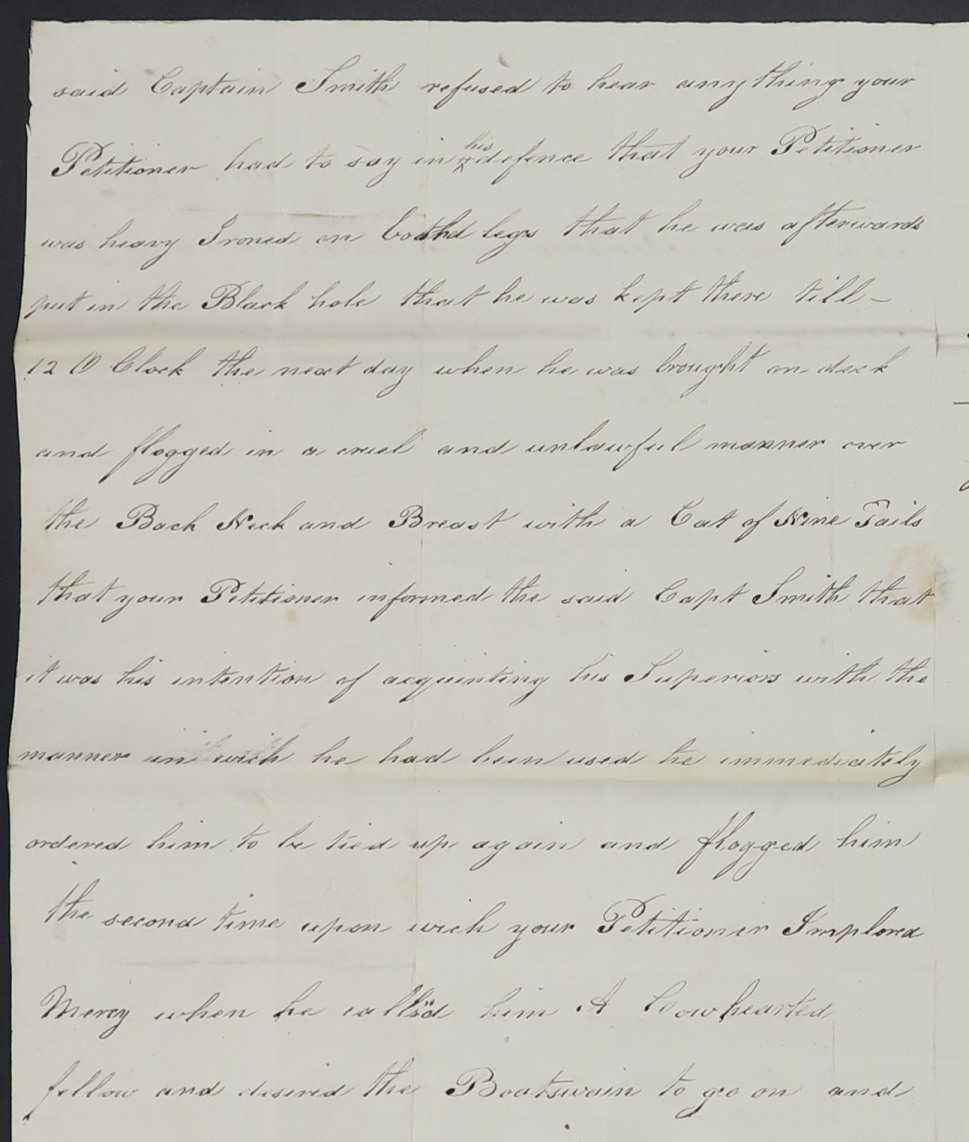

‘your Petitioner was heavy ironed on both legs, that he was afterwards put in the Black hole, that he was kept there till 12 o’clock the next day when he was brought on deck and flogged in a cruel and unlawful manner over the Back, Neck and Breast with a Cat of Nine Tails’

When Burgess told Smith that he would report him to his superiors, he claimed he was tied up and flogged again, ‘upon wich your Petitioner Implored Mercy, when he called him A Cowherated fellow and desired the Boatswain to go on and continuous Laughing all the while’. Burgess asked the Home Secretary to make enquiries and grant him redress. The Home Office clearly did look into the matter, and a copy of a letter from Smith is attached which describes Burgess’ ‘insubordination’, his ‘insolence and mutinous behaviour’. He ordered Burgess be tied up and punished in the presence of the other prisoners to set an example ‘as many of them whose conduct was getting ungovernable from an idea that no other punishment could be inflicted but being ironed in the Black hole, which many of them treat with contempt and derision’.

This horrible incident shines a disturbing light on the brutal experience of convict life, and indeed the challenges of enforcing discipline and maintaining control of the inmates.

Conditions in prisons

Life on board the convict hulks sounds particularly brutal, but we find plenty of complaints about conditions in prisons as well, with common complaints about the impact on prisoners’ health.

Writing in 1824 on behalf of convict Robert Richardson, Montague Pennington, a minister from Deal, Kent, was concerned about the conditions in the town’s gaol (catalogue reference: HO 17/39/82): ‘The gaol of this town is very ill calculated for any length of confinement, owing to its closeness, and want of yard for air and exercise; and I fear that the petitioner’s health will suffer’.

William Carus Wilson was imprisoned in Staffordshire County Gaol and in a series of letters dating from January 1838 he complained about his treatment. Carus Wilson, the son of an MP, was convicted of libel, and complained that he was ‘locked up for 14 hours out of every 24 in a damp, dark, dismal dungeon, without either fire or candle, and you may imagine how horrible the atmosphere of the place is when I tell you that it cannot be ventilated’. He further complained that he was denied access to all to newspapers or to books except the Bible, and as a tall man of 6ft 8ins, his bed was too small and his cell uncomfortable.

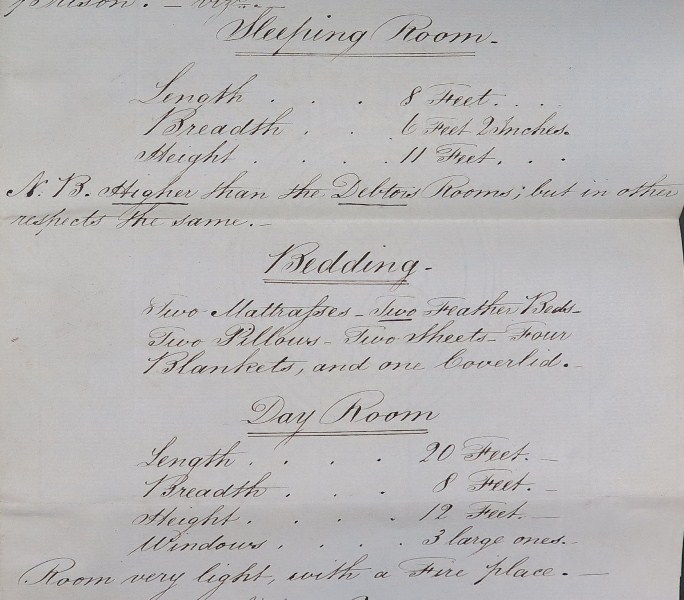

A letter from one of the visiting magistrates to the gaol disputes Carus Wilson’s claims, stating that ‘his cell is clean, dry and well ventilated and that the bed has been lengthened to the full extent of the room’. A statement from Thomas Brutton, the governor, gives details of the conditions in which Carus Wilson was kept, and names the other men in his class, one of whom attends on him as a servant. It suggests that Carus Wilson is better treated than other prisoners: ‘He does not return to his Bed Room before 8 o’clock in the evening, and gets up when he pleases. All others (except Debtors) are locked up between 4 and 5 o’clock. He is not restricted in his Dietary, being allowed to order anything he might think proper.’ These indulgences are the result of the personal interference of one of Carus Wilson’s friends, Earl Talbot, as the convict himself mentions in a letter.

Statement from Thomas Brutton, Governor of Staffordshire County Gaol, describing Charles Carus Wilson’s imprisonment (catalogue reference: HO 17/33/109)

In the convicts’ complaints and in the officials’ responses we find fascinating details that give just a flavour of what these prisoners experienced: how cold and damp they were, what they ate, the lack of privacy and what happened if they stepped out of line. Thanks to the cataloguing work being undertaken by our team of volunteers, it is possible to search Discovery, our catalogue, for key words like ‘complain’ or ‘conditions’ to find descriptions of what it was like to be imprisoned in the early 19th century.

[…] ‘A floating Hell’: life on early 19th century convict hulks […]

For further research, John Noden of Coalbrookdale, is an example of Victorian attitudes at the time, the 1820-1840 period. He survived a death sentence, thanks to Abraham Darby, strong local support, though he still had to endure a period on a hulk, and ten years of hard labour in the West Indies.

G’Day All,

I am interested in the hulk Warrior at Woolwich between 1849 and 1851. William Glanville was a guard on the Warrior when he was engaged in early 1851 to be a guard on the convict ship Pyrenees sailing for Fremantle in Western Australia. If any person has access to anything at all about the guards on the Warrior in that time frame please let me know.

Cheers, John in Western Australia

Hi John,

Thank you for your comment.

We’re unable to help with research requests on the blog, but if you go to our contact us page: http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact/ you’ll see how to get in touch with our record experts via phone, email or live chat.

I hope that helps.

Best,

Nell

I read this with great interest. It was sad to realise the brutality but a fascinating blog.

I am interested in obtaining any information for John Henry Munro(e) or possibly known as Henry John Munro prison warden on HMS Shar in Bermuda, he is my great great grandfather. I have a copy of a family history letter that his grandson wrote referencing the above facts.

Would be grateful for any info or can point me in the right direction for further research.

Many thanks

Grant McIntyre

Dear Grant,

Thank you for your comment.

To ask questions relating to research, please use our live chat or online form.

We hope you might also find our research guides helpful.

I have discovered that my 3rd great grand Aunt was imprisoned on a hulk for many months after she was sentenced to 14 years transportation.

It always amazes me that she survived this as well as the sailing to Australia.

I read this articles and cannot imagine what she went through