Just over a year into the First World War it became clear that more than just voluntary recruits would be needed to win, and conscription was considered. This started a whole new battle; one of ethics, with a number of people opposed to such measures and protests staged across the country.

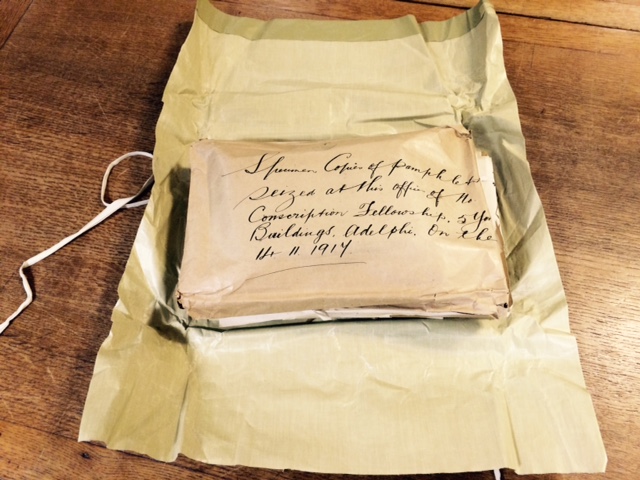

One hundred years ago, on 27 November 1915, the first national meeting of the ‘No Conscription Fellowship’ was held in London to resist this plan and support conscientious objectors. Here at The National Archives there is a record containing a parcel of pamphlets, letters and literature from the office of the No-Conscription Fellowship which was eventually seized on 14 November 1917 (PRO 10/802). It contains the Fellowship’s manifesto and a record of its activities from when it started, including newspaper cuttings, correspondence and pamphlets, including details of translating into various languages for print and worldwide distribution.

Parcel seized from No Conscription Fellowship Offices (catalogue reference: PRO 10/802)

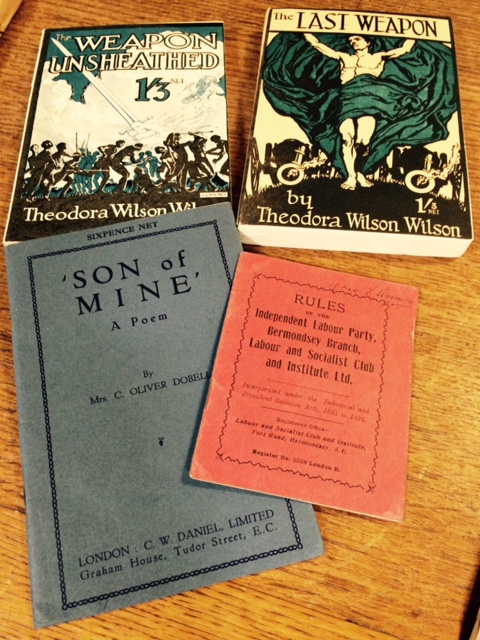

There are accounts of peace demonstrations held across the country, giving a different insight into life on the home front. It also contains a selection of books and other literature, including copies of ‘The Story of Richard Doubledick’ by Charles Dickens and ‘A Reasonable Man’s Peace’ by H.G. Wells.

Books contained in parcel seized from the Office of the No Conscription Fellowship (catalogue reference: PRO 10/802)

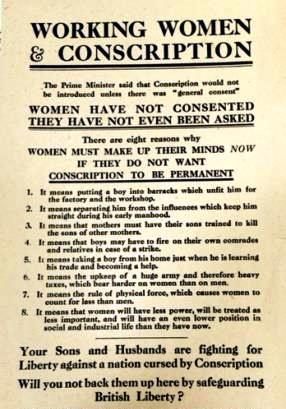

Working Women and Conscription pamphlet (catalogue reference: PRO 10/802)

One pamphlet in the parcel is specifically aimed at working women and the effects of war on their standing in society. This would have been very contentious at the time, given all the issues around women’s suffrage. However, interestingly, most of the pamphlet highlights the impact on women’s sons and husbands rather than the working women themselves.

This parcel of documents provides insight into the literature being circulated on conscription. It also provides interesting context in relation to the Conscription Appeal records from the Middlesex Appeal Tribunal (MH 47) which were digitised for the launch of our First World War 100 programme. The records in the MH 47 collection showed that only 577 out of 11,307 appeals (5%) were made by conscientious objectors, but this parcel of papers gives an idea of the sort of material and ideas that could have arguably led to their decision to object to conscription. However, most appeals were in fact for economic or family reasons. You can find out more about these conscription appeals in a previous blog by David Langrish and Chris Barnes.

Is the pen mightier than the sword?

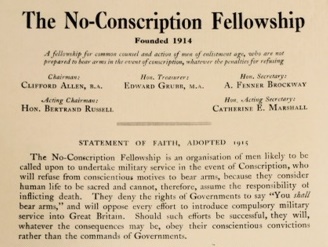

No-Conscription Fellowship membership form (catalogue reference: PRO 10/802)

One of the key people in the No Conscription Fellowship was the famous philosopher, the Hon. Bertrand Russell, author of over 70 books including The Problems of Philosophy (1912) and A History of Western Philosophy (1945). He was Acting Chairman of the Fellowship.

First World War conscription was in many ways the biggest catalyst for his engagement in ethics, social and political issues, alongside his groundbreaking works in mathematics and logic which led the analytical philosophy movement. Much like his philosophical approach to logic and mathematics, he avoided accepting principles that were taken as self-evident truths without analysing them, and this is apparent in his correspondence on the issue of conscription.

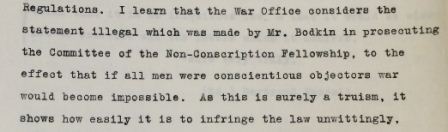

In the Home Office file entitled ‘WAR: Pacifist Activities of Bertrand Russell’, which covers the period of 1916-1921, there is correspondence between Bertrand Russell and the Home Secretary in 1916 about his lectures, which had been identified by censors for consideration under the Defence of the Realm Act 1914. As you might expect, this forced Bertrand Russell into a philosophical debate about the limits of what he could and couldn’t say within this law and how it would be judged. It resulted in a lot of correspondence back and forth to clarify the logic.

Letter from Bertrand Russell on the issue of conscription (catalogue reference: HO 45/11012/314670)

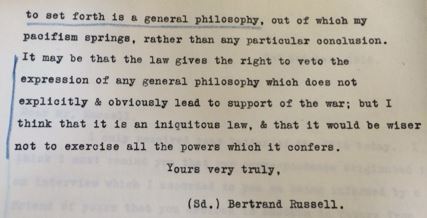

Also in this file are details of his arrests in this time, including his first arrest at Mansion House on 5 June 1916 and fine of £110 for being the author of a leaflet that was ‘likely to prejudice recruiting [conscription]’ (contained in the parcel of seized materials). There’s also an extract from a speech Russell made in Cardiff in 1916, one of many speeches monitored by a government considering his influence upon conscientious objectors.

Extract from Bertrand Russell’s speech in Cardiff, 1916 (catalogue reference: HO 45/11012/314670)

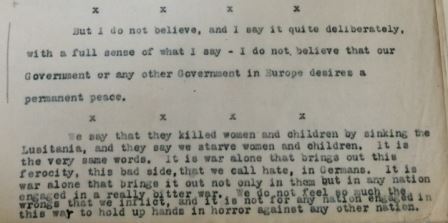

The file also reveals the details of Russell’s later arrest and incarceration at Brixton Prison for six months in 1918, following an article he wrote which was said to have libelled the British Government and American Army. It includes his request to the governor to wear his own clothes, occupy a private room, have his books and newspapers as well as have his own money for food and even some of his own furniture while in prison.

Bertrand Russell’s request for books and furniture in Brixton Prison (catalogue reference: HO 45/11012/314670)

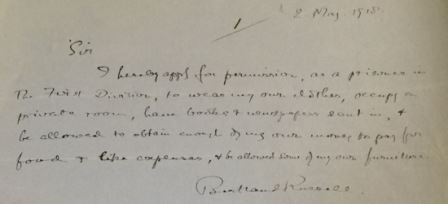

The governor recommended that this request be granted in line with Secretary of State guidelines for First Division prisoners, but there is also a letter from Russell’s brother highlighting how important it is for the ‘leading living philosopher of Europe’ to have his writing materials. He also conveyed his brother’s thoughts to the governor, taken from letters written while in prison:

‘I am growing stupid in here and have nothing interesting to say. Life is not here positively unpleasant, but only through what it lacks.’

Extract from Russell’s letter to his brother about his state of mind in prison (catalogue reference: HO 45/11012/314670)

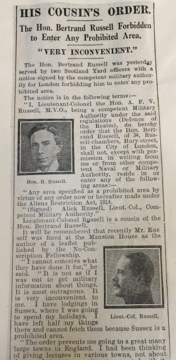

Newspaper clipping: Daily Mirror, September 1916 (catalogue reference: HO 45/11012/314670)

However, it was his cousin, Lieutenant-Colonel the Hon Alick Russell, who served the order on him so that he was forbidden to enter any prohibited area without his written permission, under the Alien Restriction Act 1914. This is shown in this clipping from the Daily Mirror dated 2 September 1916, but the file also labels Bertrand Russell’s ‘whole course of action as dangerous’, with his speeches to conscientious objectors cited as one of the reasons for the order.

While Russell felt he was ‘growing stupid’ in Brixton Prison, he still managed to write the majority of an Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy while inside (published in 1919). This was a great achievement by most people’s standards, but perhaps not for a man famous for saying ‘The whole problem with the world is that fools and fanatics are always so certain of themselves, but wiser people so full of doubts’. He was discharged from Brixton Prison on 14 September 1918.

Recognition for a lifetime’s work

Bertrand Russell’s lifetime campaign for peace can be traced through the collection of records held at The National Archives, with files relating to his views on the First World War, Second World War, Cold War and issues such as nuclear disarmament, right up until his death in 1970.

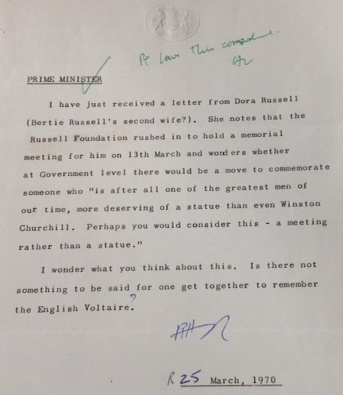

While the files reveal several clashes with government in relation to his pacifist views, they also reveal the success of his 40 year career campaigning for human rights and education reform, as well as his literary and philosophical achievements. A Prime Minister’s Office record (PREM 13/3120) from 1970 reveals a proposal put forward by the Secretary of State for Social Security to Prime Minister Harold Wilson, following Russell’s death. It asks government to provide a memorial meeting to ‘remember the English Voltaire’. The note provides a quote from Bertrand Russell’s second wife who stated that he was ‘more deserving of a statue than Winston Churchill’, which I’m sure some people would contest – perhaps even Russell himself.

Note to Prime Minister requesting a memorial meeting for Russell (catalogue reference: PREM 13/3120)

Wilson did not approve the memorial meeting because it was ruled that these events should only be for royalty, prime ministers and a few heads of state; not for individual cases, unless ‘they were organised privately (as is the case of Ghandi)’.

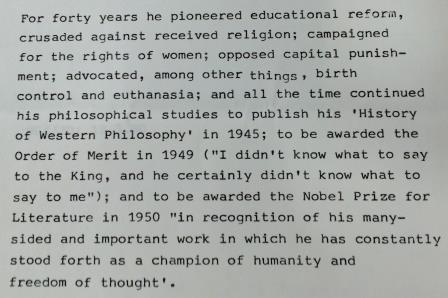

While the government did not hold an official memorial meeting for Russell his impact was clearly and universally recognised after being awarded the Order of Merit in 1949, closely followed by the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1950. The file WORK 16/2735, covering the years 1978-1983, concerns the plaque for Pembroke Lodge in Richmond Park, the Russell family home where Bertrand Russell lived until aged 18. Within it there is a summary of Bertrand Russell’s lifetime achievements, highlighting his recognition as a ‘champion of humanity and freedom of thought’, showing that perhaps he was right in saying ‘Do not fear to be eccentric in opinion, for every opinion now accepted was once eccentric’.

Extract from note on Russell’s achievements (catalogue reference: WORK 16-2735)

[…] Just over a year into the First World War it became clear that more than just voluntary recruits would be needed to win, and conscription was considered. This started a… Go to Source […]