The definition of the word ‘place’ can be based on a relationship between the personal and a location: ‘He put me in my place’; ‘She walked to her place at the table’; ‘we danced at Dave’s place all night’. Each example hints at a person, or thing belonging to a particular spot or point in a space – which is usually designated by the word place.

Both anthropologist Marc Auge[ref]1. Augé, M., 2008. ‘From Places to Non-Places’ in: Non-Places: An Introduction to Supermodernity. London: Verso, 1995[/ref] and geographer Tim Criswell[ref]2. Cresswell, T., 2008. ‘Defining Place’ in: Place: A Short Introduction. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2004[/ref] allude to this idea in their writings on space and place. Each suggests that in order for meaning to be associated with a space, there must be a sense of relation and an aspect of personal belonging associated to it.

My interests lie in understanding this moment when and the reasons why a particular space can become a place to those that used it. When I consider the role of LGBTQ spaces throughout history I think about the effect they had on people’s everyday lives. By doing this I can start to understand why they became places that were familiar, comfortable, and safe.

Regardless of whether you go somewhere every day or just once a month, if there is a sense of belonging or meaning associated with that space it will invariably be linked to one’s own personal identification.

However, it is easy to begin to get lost in the changing relationship between space and place, because each space has its own meaning for each individual that uses it; these meanings can become clouded and confused. By picking apart how the space was used, what it was for and why people went, one can begin to shed light on their importance as places. I do this within my own research, which is focused on gay men’s nightclubs in 1980s London; I am learning that these were places people could go to experience pleasure, feel less isolated and create nocturnal communities and networks, all to a serious backdrop of music, people and safety.

The Shim Sham Club

Working for the Queer and the State event at The National Archives allowed me to explore new archival material and think about the relationship between queer space and place in a new context.

I was drawn to a set of documents on the 1930s club called the Shim Sham Club. The Shim Sham was a gay-friendly jazz club that originally opened in 1935 at 37 Wardour Street in Soho. The place was known for being an unregistered club that held bottle parties as a way of avoiding out-of-hours licensing issues, thus constantly attracting police attention.

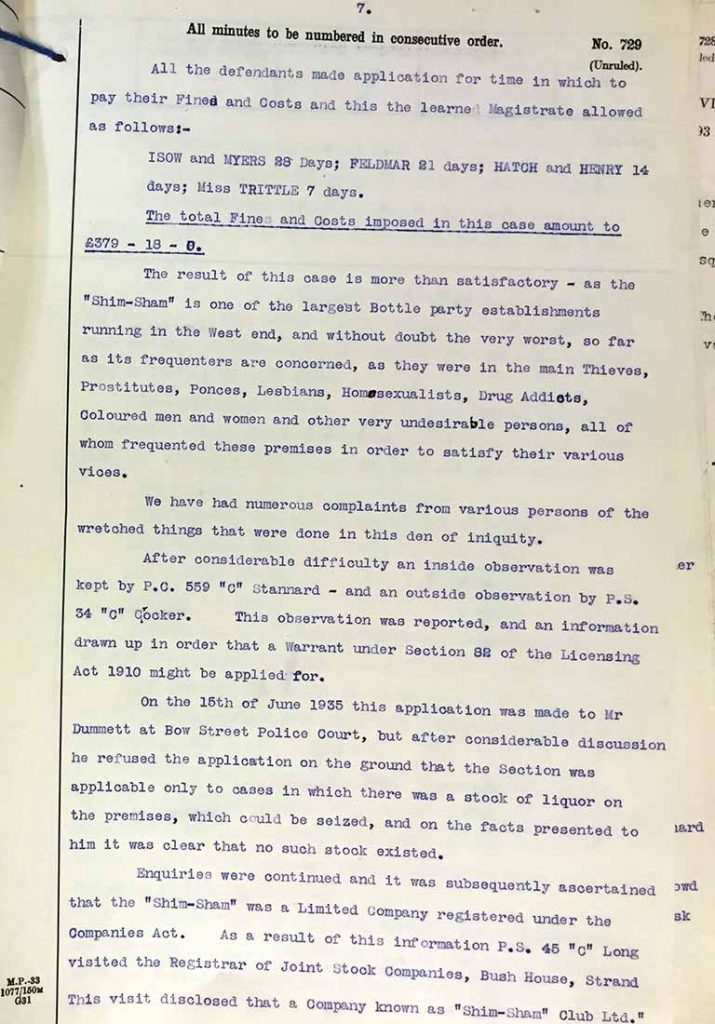

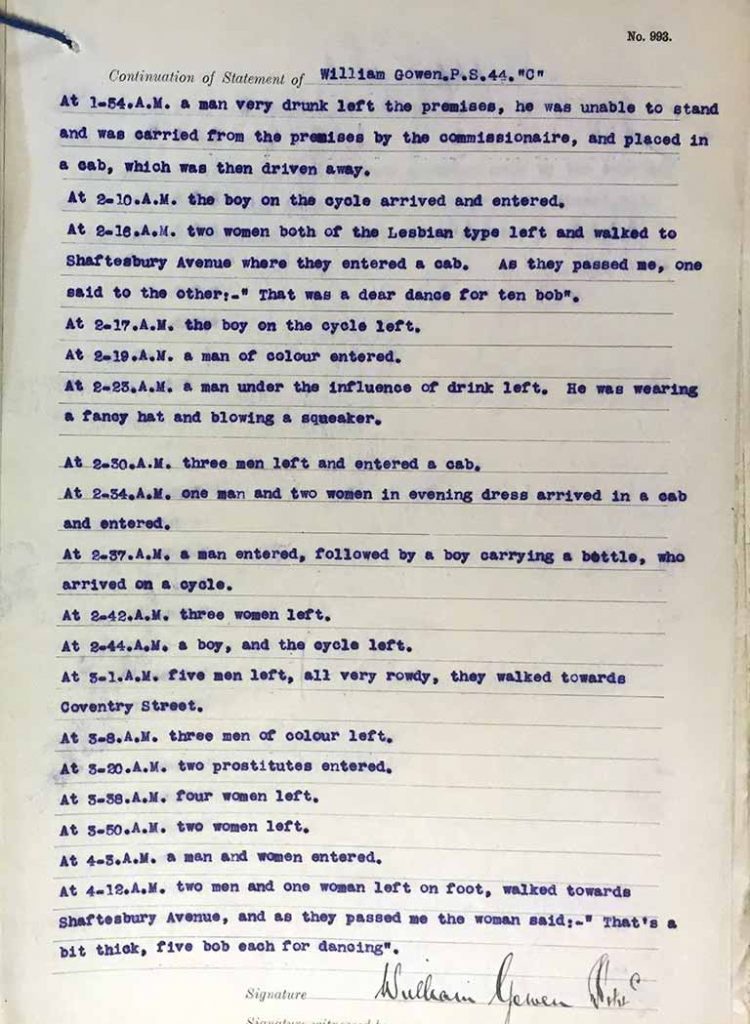

The material consisted of police reports highlighting the space as a ‘den of vice and iniquity’. The reports were made by a ‘plain clothed’ officer who appears to be investigating the alcohol consumption, the clientele and their behaviour. He made comments on the availability of alcohol out of hours, disguised under the name of ‘Bottle Parties’ – which meant that the patrons of the club could consume, dance, and become ‘incapably drunk’.

- Police observation on the Shim Sham, being observed as an unregistered club and for the sale of liquor out of hours (catalogue reference: MEPO 2/4494)

- Police observation from 1938 of the reopened Rainbow Roof, previously named the Shim Sham (catalogue reference: MEPO 2/4494)

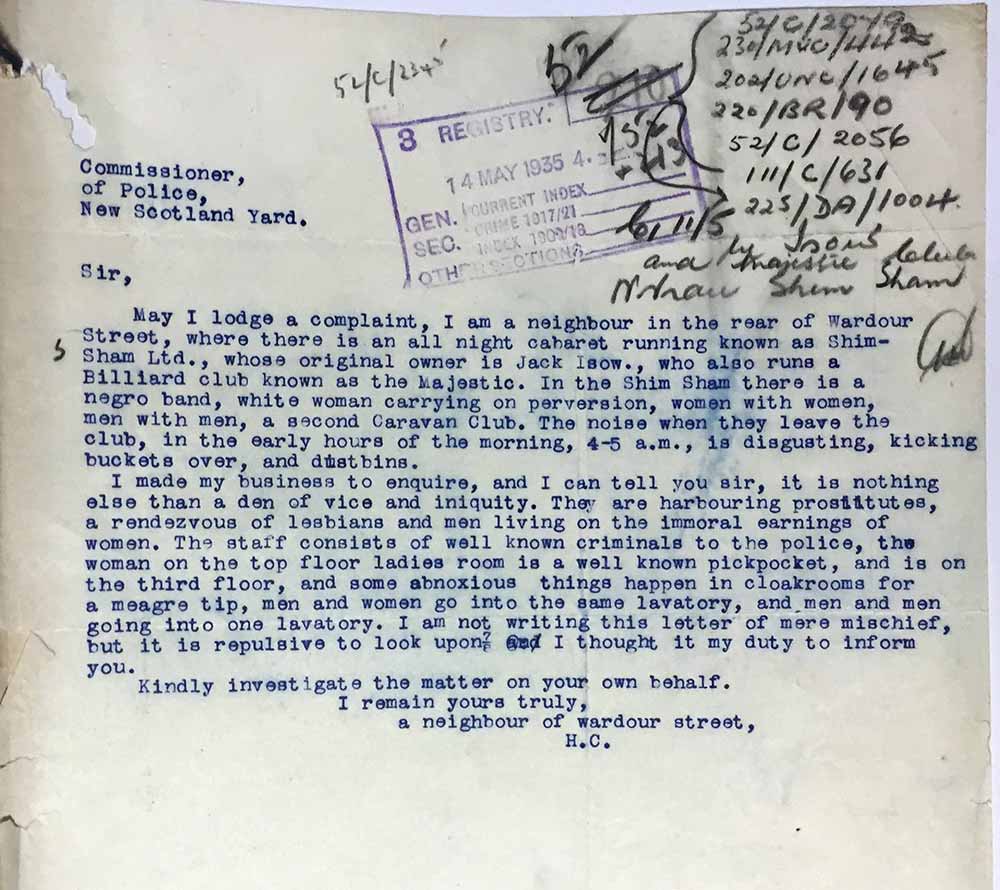

There was also a series of letters from local residents who protest their dislike of the club to the police, describing the place as one of ‘infamy, frequented by criminals and prostitutes’. Each letter condemns the noise, behaviour and the clientele that emerge from the club, commenting on ‘a white woman carrying on perversion, women with women’ and how ‘disgusting’ the noise is at 04:00-05:00 in the morning.

Letter of complaint from ‘a neighbour of wardour street’ which prompted police observations of the Shim Sham club, 1935 (catalogue reference: MEPO 2/4494)

The voice of the reports, from both the officer and the local residents, seems disapproving of the liberal attitudes within the club, highlighting what comes across as immoral behaviour. This material surrounding the 1930s club, therefore, clearly demonstrates the high level of surveillance that was placed on this establishment, and others like it.

However, regardless of the negative connotations that come with this idea of surveillance I could also use these records to uncover creative uses of the space, and consider what the club was all about.

Most prominent was a clear appreciation of music and dance: one of the records questioned the club’s musicians, who seem to play an important role in the atmosphere of the evening; another comments on the continued filling of the dance floor. The name of the venue itself suggests the appreciation and prevalence of African American culture and dance – the Shim Sham was a tap dance originating in Harlem.

Other than these, liberal attitudes towards alcohol and sexuality within the space were also brought to my attention, with one letter suggesting ‘men and men going together into one lavatory’. The diverse clientele, for example Jack Isow, a Polish Jew born in Russia, and the African American singer Ike Hatch, caused much contention with the police, but were very much rooted within the space.

While being careful not to make sweeping statements about what this club meant to those who used it at the time these records have allowed me to think harder about the importance of having a safe place in which to dance, and enjoy oneself into the night. I believe there is an importance in nightlife spaces as separate places from the everyday; thereby there is a necessity to celebrate, uncover and understand their history and what they meant to those that used them.

It was an extraordinary experience to be able to explore archival records of these liminal spaces, and recreate the Caravan Club for an event that was seemingly such a great celebration of queer spaces and LGBTQI+ history.

Queer City: London Club Culture 1918-1967, a collaborative project between The National Archives and the National Trust, is now open at Freud Café-Bar, 198 Shaftesbury Avenue. For more information visit: www.nationaltrust.org.uk/queer-city-london

Ike Hatch made a number of recordings for Regal Zonophone in 1935/6. He also featured in the BBC radio series “The Kentucky Minstrels” which celebrated the blackface tradition, and ran from 1935 to 1950.