Julia Margaret Cameron, the Victorian photographer, was anything but ordinary. She was often described by those who knew her as full of energy and vibrant; it’s not surprising she had many friends. And with Cameron’s strong links with India[ref] 1. She was born in India; her father was an East India Company Official. [/ref] it was only a matter of time she became friends with Sir Henry Taylor and his wife (when they became next door neighbours in Kent). Taylor was not only a successful author at the time but also a senior civil servant at the Colonial Office.

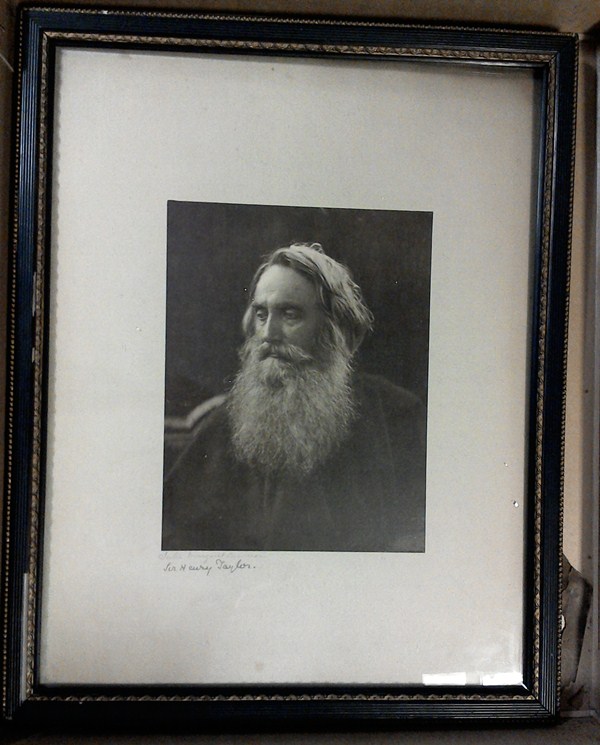

Sir Henry was the subject of many photographs by Cameron, as himself or in character.[ref] 2. Characters from literary works or historical scenes. [/ref] Kept at The National Archives as part of the CO 1069 collection is a framed albumen print of Taylor, which as an archival object is ‘seen’ rather than ‘viewed’ as a gallery exhibit.

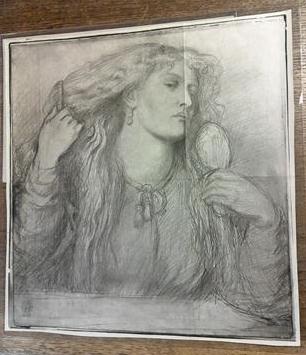

Framed albumen print of Sir Henry Taylor (front). Photograph portrait by Julia Margaret Cameron, dated 1865 on The National Archives’ catalogue (Catalogue reference: CO 1069/919)

The photograph of Taylor in our collection is dated 1865 (as taken from our catalogue) and we can surmise that it is a version of the photograph of him that appears in the Herschel Album (it is likely that it was given to Taylor from Cameron herself). [ref] 3. A version of this image of Taylor (from The Hershel Album) appears in the exhibition at the Science Museum and The V&A to mark the bicentenary of Cameron’s birth. The various copies positioned and framed in slightly different ways in both exhibitions and here as an archival object give us different angles and perspectives on the photographic image’s reception within her career, her relationships with others as well as the archival collections of her photographs. [/ref]

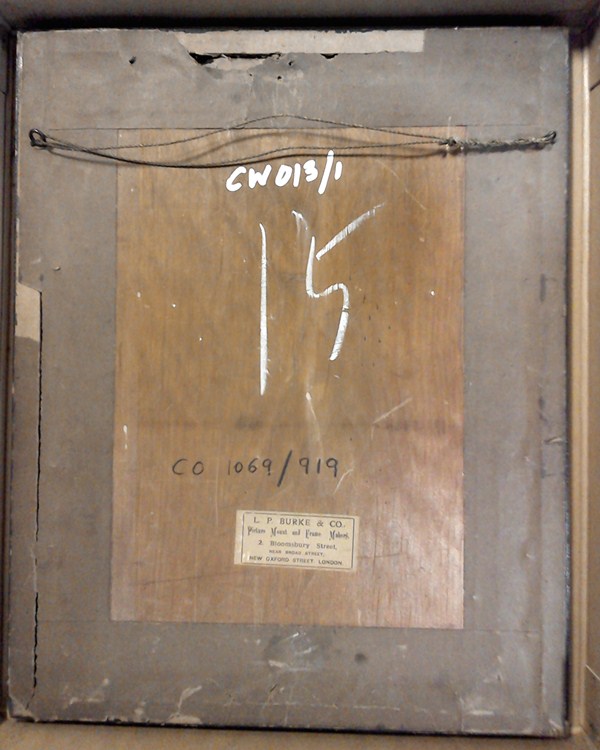

Framed albumen print of Sir Henry Taylor (back). Photograph portrait by Julia Margaret Cameron, dated 1865 on The National Archives’ catalogue (Catalogue reference: CO 1069/919)

The Herschel Album contains 94 photographs with annotations made by Cameron and was a gift to her friend and mentor, the scientist and photographer Sir John Herschel. It contains photographs she made during the period 1864–1867 and includes portraits of Alfred Tennyson, other friends and family members.

In many ways Cameron was a very conventional lady: she was a devoted mother and a wife. But this is where convention ends. She took up photography later in life (as introduced by Hershel) and this changed the course of her life.

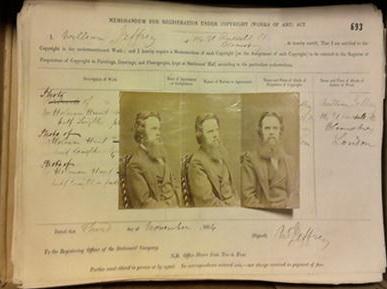

Cameron was not afraid to break free from conventions. Images like the one of Sir Henry Taylor pictured above does not necessarily look experimental to our modern eyes. However, on closer inspection it is not a typical photograph of the time. Compare it to a series of standard portraits of Holman Hunt taken by another photographer and you see that it’s not similar in how it was taken, and that the photographers have different intended outcomes. The print of Taylor has some similarities with the framing of subjects in portraiture you encounter in paintings and it’s stylistic (from posture, the relationship of the subject with the viewer to photographic technique).

Example of an conventional image of William Holeman Hunt in COPY 1.

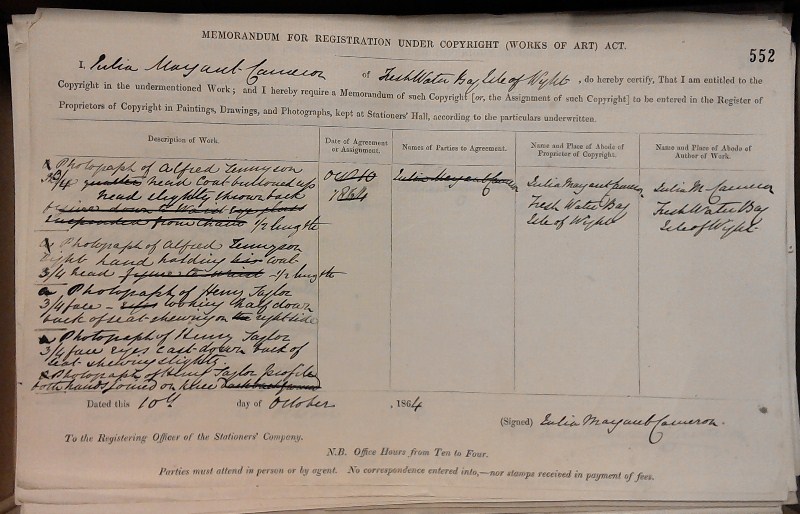

The archival trail on the copies of her photographs at The National Archives goes cold after that. Although Julia Margaret Cameron registered many of her photographs at The Stationers’ Hall to protect them from copyright infringement [ref] 4. This collection is a rich source of examples of photographs, copies of drawings, paintings, commercial labels and advertisement. Many of these entry forms contain photographs which were ‘annexed’ or attached to the form in the collection COPY 1 from 1837 to 1912. [/ref] none of the copies of her photographs were submitted as part of her applications, as it was not compulsory requirement. Instead, the application entry forms she submitted (which subsequently became part of the collection in COPY 1) contain Cameron’s own detailed descriptions of her photographs; here are the descriptions of the photographs of Sir Henry Taylor dated 1864. It is interesting to see how she phrased the descriptions of her work (there’s plenty of examples where she amended her own descriptions on the entry forms she submitted).

Within the wider context of early photography, Cameron’s work pushed the boundaries of turning photography into an art form. It shaped how sitters were portrayed, captured and subsequently received by the Victorian audience. Our modern minds can still learn something from her approach: not being completely bound by the rules, and seeing where creativity takes us.

While artists such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti were influenced by photography as it rapidly developed as a medium (with its suggestion of captured moments, and the minute detail entailed even with early photography), Cameron’s work was influenced the way the Pre-Raphaelites portrayed subjects in paintings. She made every effort to elevate photography as a form of fine art. Her subjects were often components of a scene of a ‘high Renaissance painting’ in the contrived posture of her subjects, the way multiple subjects related to each other, their facial expressions and the occasional title to focus the viewer’s attention. This overlap of the work of artists and photographers was an exciting time in terms of the developments in art and technology.

Cameron made albumen prints from the wet collodion glass negatives. Albumen prints were by far the popular choice for photographers for the period between 1860s-1890s and one of its unique properties was its ability to capture very fine details. However, Cameron’s tended to take her photographs slightly out of focus which created this ‘blurred softness’ in her subjects. By doing so, she did not utilise the quality of albumen prints in the sense that taking it out of focus meant disregarding the finer minute details. [ref] 5. For more information about her working methods, see the V&A website. [/ref] Even so, she often chose to keep prints which had smudges and scratches (which would have been disgarded by other photographers). This aspect of her working method was thus heightened by the properties of the albumen print.

She used photographs as a means to establish a different approach within the limitations of photographic equipment and established processes at the time, which we take for granted today. Thus one can say she was an experimental and a daring lady.

Find out more

See the exhibitions Julia Margaret Cameron at the V&A (28 November 2015 – 21 February 2016) and Julia Margaret Cameron: Influence and Intimacy at the Science Museum (24 September 2015 – 28 March 2016).

Surely when talking of Sir Henry Taylor it should be Sir Henry and not Sir Taylor, it is only when they are a Lord and Lady that you call them Lord Brown for example.

Thanks for flagging this up. It has been amended.