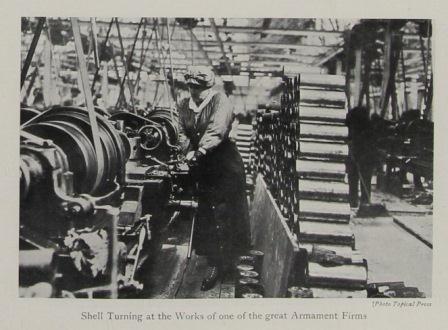

A female worker ‘Shell Turning at one of the great Armament Firms’, from the 1916 government publication ‘Women’s War Work’ (catalogue reference: MH 47/142/1)

In part one of our blog series on female munitions workers, my colleague Vicky detailed how the work of women and girls in Britain’s industry became increasingly vital as the pressures of war siphoned off the male workforce.

As Vicky pointed out, the essential and visible role that women played in keeping Britain supplied made clear their competence and value, with the Adjutant General to the forces commenting in 1916 that:

‘Women have shown themselves capable of successfully replacing the stronger sex in practically every calling’.[ref]1. Women’s War Work (catalogue reference: MH 47/142/1)[/ref]

Such a condescending tone towards female workers was sadly common during the First World War. However, rather than just accepting their role as patronised patriots, many female workers seized upon the recognition of their work, contending that if their work was equal to a man’s, their pay must be also. This blog will focus on the issue of and the struggles (both successful and unsuccessful) for equal pay by women, and women’s trade unions such as the National Federation of Women Workers, whose Woman Worker magazine provides a fantastic insight into the issues facing female workers in the war.[ref]2. Copies of the Woman Worker can be viewed in the Trade Unions Congress Library Collections, housed at London Metropolitan University, https://metranet.londonmet.ac.uk/services/sas/library-services/tuc/[/ref]

‘Equal for pay for equal work’ was an important issue before the war, when most women did not earn enough to support themselves, but the need for wage equality and collective organisation among female workers seemed to become more pertinent during the First World War. Unlike before, many women were doing work previously carried out by men, and trades whose wages were once only decided by their owners and the whims of the market had become ‘controlled’ by the Ministry of Munitions during war time.

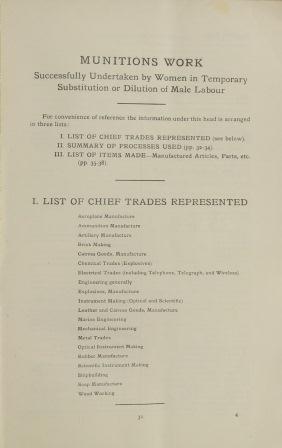

A list of ‘Munitions Work Successfully Undertaken by Women in Temporary Substitution or Dilution of Male Labour’ from the 1916 government publication ‘Women’s War Work’ (catalogue reference: MH 47/142/1)

In the negotiations leading up to the 1915 ‘Treasury Agreement’ with trade unions and manufacturers that allowed women into men’s jobs, it was set out that, to protect post-war male wages, a woman doing the same job as a man should be paid at the same rate. The famous circular ‘L.2’, with its promise of ‘equal pay for equal work’ was issued in October 1915.

Although the circular and the Munitions of War Act gave the government the ability to enforce equal wages in controlled trades, and set a minimum weekly rate of 20 shillings for women doing skilled ‘male’ work, employers often circumnavigated the edict. ‘Male’ jobs were often ‘diluted’ (broken down into multiple processes) to avoid being labelled ‘equal work’; and while 20 shillings was a minimum, it came to be interpreted as a standard, often to women’s detriment.[ref]3. Angela Woollacott, On Her Their Lives Depend, University of California Press, London, 1994, pp.113-114[/ref] Ministry of Labour files held by The National Archives detailing the Industrial Commissioner’s role in arbitrating workplace disputes, show many cases where the letter, rather than the spirit, of ‘equal pay for equal work’ was used to undermine women workers’ campaign.

For instance, in 1916 an arbitration session was held over a dispute between the Vickers shell factory in Barrow-in-Furness, and women represented by the National Federation of Women Workers. The women contested that they were engaged in ‘men’s work’ for which their male counterparts received 26 shillings per week, but were only paid 18-20s. The arbitrator did not uphold the women’s complaint, being swayed by Vickers’ arguments that the women’s wages were in line with circular L.2 and that the war gave rise to the need for ‘the greatest possible economy in the cost of producing munitions’.[ref]4. LAB 2/420/IC912/1916 – Chief Industrial Commissioner’s Department: Munitions Industries: Arbitration Awards. Vickers Ltd., Barrow-in-Furness v National Federation of Women Workers (W.W. Mackenzie)[/ref]

Government arbitration over wages was often a long-winded and fruitless process for women, the Woman Worker commenting that the very word arbitration had, ‘a disagreeable sound to some of our members. It means to them waiting and disappointment’.[ref]5. Woman Worker, March 1916, p.10[/ref]

However, although clearly frustrating, arbitration was sometimes instrumental in winning small victories for both unionised and self-organised women looking to improve their lot. In July 1916, the National Federation of Women Workers managed to secure its members at D Napier & Sons in London, engaged as fabric hands in the production of aircraft, an increase in their hourly rate to 5d (pence).[ref]6. Catalogue reference: LAB 2/420/24[/ref] This 5d rate represents a significant victory for the women, it being 1d higher than the standard rate set by the Ministry of Munitions for ‘munitions work which prior to the war was not recognised as men’s work’.[ref]7. Catalogue reference: EXT 1/315, part 21[/ref]

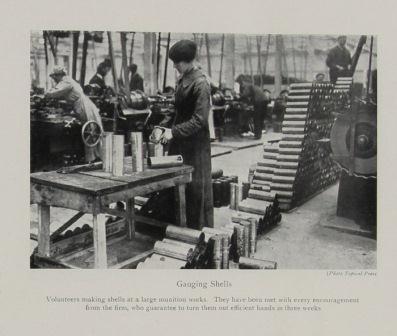

A female worker gauging shells, from the 1916 government publication ‘Women’s War Work’ (catalogue reference: MH 47/142/1)

Arbitration was also a successful route for self-organised women to settle disputes. Mrs Ada Gutteridge was the leader of a group of women manufacturing cartridge cases at Vickers’ Birmingham works. Through the arbitration process in 1916 Mrs Gutteridge complained that their piece-work rate was unfairly low. These self-organised women managed to up their rate from 6/3d (seven shillings three pence) per hundred cases to 7/3d, a sizeable increase.

These instances show that while not a forum in which female workers could achieve massive advances, arbitration did allow women to successfully press for change. Furthermore they are evidence that female workers, both unionised and unaffiliated, were aware of the opportunities for collective bargaining afforded to them by the government control of industry in the First World War and were willing to utilise them.

The working conditions imposed on women in the First World War rendered arbitration one of the few ways they could reasonably achieve a wage increase, as leaving for ‘greener pastures’ was made impossible because of the need for a ‘leaver’s ticket’. However, official arbitration was not the only weapon that women workers utilised against poor wages and other maltreatment. Indeed, despite restrictions on industrial action under the Defence of the Realm Act (DORA) Ministry of Munitions labour reports show that female workers did regularly manage to agitate for strike action over a wide variety of issues, something which our third and final blog in this series will explore.

Thank you for these blogs on Women Munitions Workers in WW1. I have a photo of my maternal grandmother and a co-worker (unnamed) who were working at a Munitions factory, probably in the Richmond, Surrey area. They are wearing the smocks and caps shown in your article. I look forward to the third blog/article.

An interesting article. I believe my grandmother worked at the Leeds munitions factory – I would love to know if is there a record anywhere of the employees and the jobs they did.