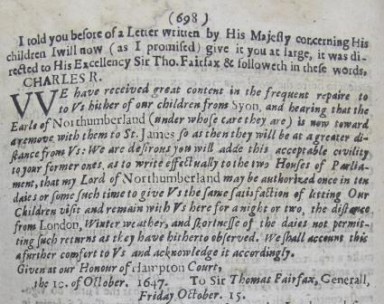

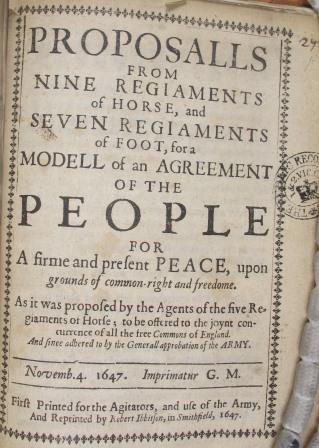

Title page of the ‘Agreement of the People’, printed at Smithfield by George Ibbitson (catalogue reference SP 116/530/23)

Three hundred and seventy years ago this autumn, among the dying embers of bloody civil war, emerged what was to be the first truly democratic pressure group in British political history.

By the end of the First Civil War (or war of the Stuart Kingdoms), the divisions of 1642 had become further complicated by the formation of the New Model Army in 1645. Valuing merit and proficiency above privilege and social standing, in 1648 it was to use force against a Parliament that wished to disband it.

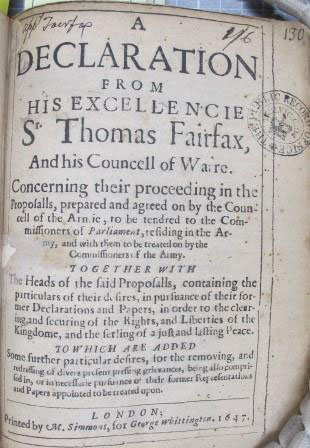

During the summer of 1647, attempts by parliamentary commanders – army grandees like Thomas Fairfax and Henry Ireton – to negotiate a settlement with Charles I lost them the support of the military and civilian radicals (or ‘Levelling’ party) within their ranks.

The Levellers particularly criticised Ireton for behaving in a servile way towards the king. They accused the senior officers of betraying the interests of the common soldiery and people of England.[ref]1. They distributed pamphlets such as ‘England’s Freedom, Soldier’s Rights’, which were often worn in the soldier’s hatbands (together with a sea-green arm ribbon) to show their support.[/ref] They also criticised the Long Parliament itself, for their mounting arrears of pay and its readiness to reach an accommodation with Charles.

In October 1647, five of the most radical cavalry regiments elected agitators known as ‘new agents’ to represent their views. They issued a political manifesto, ‘The Case of the Armie Truly Stated’, which endorsed proposals drafted by their civilian representatives (like ‘Free Born John’ Lilburne).[ref]2. Lilburne (a parliamentary hero of the Battle of Brentford) would write his tract ‘England’s Birthright Identified’ from imprisonment in 1645. Being incarcerated in the Tower for denouncing the Earl of Manchester as a traitor and Royalist sympathiser, he would also regard the Protectorate during the following decade as being more tyrannical than the Caroline government itself.[/ref] This, in turn, influenced the far more controversial Agreement of the People, which advocated ‘a firm and present peace upon the grounds of common right and freedom’. This latter work was probably drafted by the agitator and future Williamite Postmaster-General, John Wildman.[ref]3. As an arch-conspirator, Wildman continued to plot against the Crown into the 1690s.[/ref]

The Levellers were more a political movement than a party, as they didn’t conform to a specific manifesto. However, they were organised at national level, and held meetings in a number of London taverns (like the Rosemary Branch in Islington).

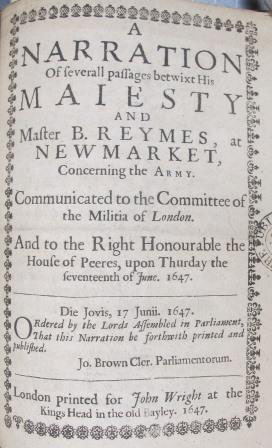

Broadsheet reporting the negotiations at Newmarket between the King and the New Model Army (catalogue reference SP 116/530/42)

From October to November, New Model Army soldiers and officers gathered at St Mary’s Parish Church in Putney, to discuss the constitution and the future of England. The most senior officer present was Thomas Rainsborough, a former MP for Droitwich and serving officer at sea in the fleet of the parliamentary ‘Irish Guard’.[ref]4. Rainsborough was killed in a bungled Royalist attempt to kidnap him during the siege of Pontefract in October 1648.[/ref]

Many questions were raised at the Putney Debates. Should they negotiate a settlement with an already defeated king? Should there even be a monarchy or a House of Lords? Should the right to vote be limited only to property holders? Would democratic changes threaten the existing social order, as conservatives like Ireton and Cromwell (his father-in-law) believed?

That summer, King Charles was abandoned to his fate by the Scottish army of the Covenant at Newcastle [ref]5. ‘Sold to the English Parliament’, as many Royalist propagandists maintained, after his rejection of the ‘Newcastle Propositions’ and utter refusal to take the Kirk and establish Presbyterian Church government. P Greg, ‘King Charles I’ (London, 1981), 411.[/ref] He attempted to negotiate with the New Model Army at Newmarket and side with them against Parliament (following his seizure by Cornet Joyce at Holdenby House).[ref]6. Joyce, a junior officer in Fairfax’s Horse had placed the king into the protective custody of the New Model Army.[/ref]

Playing both sides off against each other, the King was taken to London by orders of the Army Council and confined to the palatial splendor of Hampton Court. He petitioned that he should be joined there by his sons: James Duke of York,[ref]7. Prince James (the future James II) would escape from Syon to France, and initially saw military service with the Bourbons under the famed Marshall Turenne.[/ref] and the young Prince Henry of Gloucester. They were both being held nearby at Syon House, under the guardianship of the former Lord High Admiral, the Earl of Northumberland. However, Charles’ petition was unsuccessful.

- Despatch relating to Charles I’s request to be joined by his children at Hampton Court Palace (catalogue reference SP 9/248/14/698)

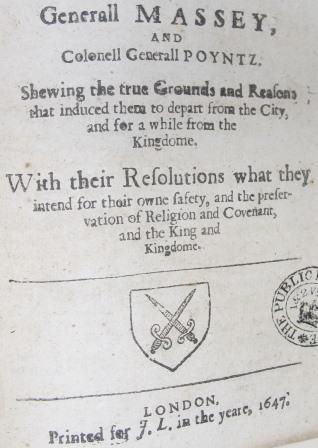

- Declaration of Generals Massey and Poyntz on their flight from the City. With their resolutions for the preservation of ‘Religion and Covenant, and the King and Kingdome’ (catalogue reference SP 116/530/49)

In early 1647, Northumberland had sided with Edward Montague, Earl of Manchester (Cromwell’s former superior in the Eastern Association) and the Presbyterians against the religious Independents of the New Model Army, as they attempted to draw up terms acceptable to the king.

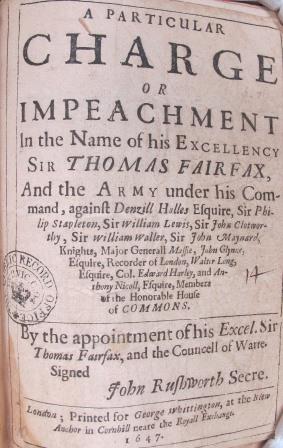

The charge of impeachment against Denzil Holles (and other leading Parliamentarians), signed by John Rushworth, Secretary to Sir Thomas Fairfax (catalogue reference SP 16/530/14)

The dispute grew between the forces of moderate Presbyterianism and the army’s move towards independency. Two of Parliament’s most successful wartime commanders – Generals Edward Massey (celebrated for his resolute defence of Gloucester) and Philip Sydenham-Poyntz – fled from London to take refuge with the Royalist émigrés in Holland. This flight followed Fairfax’s earlier impeachment of Denzil Holles, leader of the Parliamentarian moderates in the Commons, who was personally opposed to Cromwell and ‘war party’ extremism.[ref]8. Holles was duly accused of trying to revive the civil war in the Presbyterian interest.[/ref]

Rainsborough emerged as the highest-ranking Leveller sympathiser, calling for an end to negotiations with the king (the so-called ‘man of blood'[ref]9. The phrase was officially endorsed by the army leadership (during the three day prayer meeting at Windsor Castle in April 1648) as a result of Charles’ secret treaty, ‘The Engagement’ with the Scots Commissioners at Carisbrooke, which agreed to a religious settlement. T. Corns, ‘The Royal Image: Representations of Charles I’ (Cambridge, 1999), 88.[/ref] who had plunged the nation into conflict). He also wanted to force through a new constitution. Other Leveller spokesmen included the agitators William Allen and Edward Sexby (who would attempt to assassinate the Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell, in 1655).[ref]10. As part of a desperate scheme to launch a Spanish backed joint rising of Royalists and Levellers.[/ref]

The debates at Putney (which begun on 28 October) centered on the franchise. The radicals regarded the right to vote as fundamental to all freeborn Englishmen – a right which had been won by fighting on the battlefield. The military hierarchy did not accept the Leveller’s motion that the Agreement of the People should be adopted as the army’s official constitutional programme; however, they did vote for a mass rendezvous at which the agreement was presented to the troops.

![‘The Moderate Intelligencer’: Council of the Army at Putney, request for payment [of arrears] and free quarter (catalogue reference SP 9/246/32/296)](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/01150840/Lev-5-requests-of-army-at-Putney-1.jpg)

‘The Moderate Intelligencer’: Council of the Army at Putney, request for payment [of arrears] and free quarter (catalogue reference SP 9/246/32/296)

Declaration by Fairfax and his Council of War in the ‘Heads of the Proposals’ (catalogue reference SP 116/530/20)

Ultimately, Charles’ escape to the Isle of Wight on 11 November dramatically changed the situation. After the breakdown of the talks at Newport, the New Model Army would close its ranks as a second civil war threatened. The representation of the rank and file soldiery on the Army Council was dropped in 1648. However, many officers – who, ironically, had not been in favour of the Leveller agenda –supported the regicide of the king in January 1649 and had to reconsider their political positions.

The Levellers directly inspired Gerrard Winstanley’s agrarian commune of Diggers (or ‘True Levellers’) at Weybridge during 1649-50. Morever, the Levellers greatly influenced both the Enlightenment ideals of France in 1789 and the early Victorian Chartist movement.

The historic events on the banks of the Thames in Surrey – manifest in such tracts as ‘The Case of the Armie’ and the iconic ‘Agreement’ itself – saw ordinary troopers and foot-soldiers take on the military grandees to argue for greater democracy; they provided a platform for the common people to make their voices heard.