If you were to list the battles which most affected the history of the British Isles, which would you choose? If you went back to the Middle Ages, you might choose the Battle of Hastings, fought on 14 October 1066 between Duke William of Normandy and King Harold II of England. This is arguably the most iconic battle ever fought, at least on English soil.

William’s victory transformed land ownership as the Norman aristocracy largely supplanted their defeated foes. Political, religious and linguistic culture, as well as the built environment and the landscape, witnessed dramatic change, some of which can still be seen in Domesday Book, shortly to be on display at the British Library during their Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms: Art, Word, War exhibition.

There is, however, another battle sharing its anniversary with Hastings that is less well known but that had important implications for the political, social and economic geography of our islands. Seven hundred years ago, on 14 October 1318, at Faughart near Dundalk in Ireland, men loyal to the English king from counties Louth and nearby Meath defeated an occupying Scottish army. Its leader, Edward – the only surviving brother of and heir presumptive to the Scottish king, Robert Bruce – was killed, his head sent to the English king, and his army chased from Ireland. 1

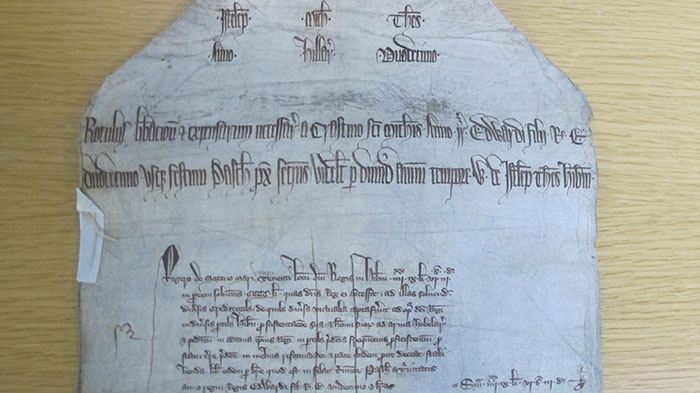

SC 13/K52G, obverse and reverse views of the seal of Robert Bruce, king of Scots, 1306-29

For the English, Faughart ensured that its predominance within the British Isles built up over the previous 250 years would be maintained, at least for now. The Scots were temporarily thwarted in their ambitions to broaden the military front to force the English to negotiate and recognise their independence and the dynastic rights of King Robert. 2

Landing near Larne in County Antrim on 26 May 1315, Edward Bruce and several thousand veterans had launched a well-planned, full scale Scottish invasion of Ireland, three and a half years previously. 3 Within weeks, Edward had been crowned king of Ireland. This was a direct threat to English lordship in Ireland, part of the dominions of the English crown since the conquests of the late-12th century and expansion and settlement (of both government and lordship) of the 13th century.

But no English king had set foot in his lordship since John in 1210. The present king, Edward II, was in no place to react swiftly, following his seismic defeat by the Scots at the Battle of Bannockburn in June 1314. This permitted the Scots to take the military initiative over the next three years and attempt, arguably, not only to conquer Ireland but to extend their ambitions to Wales, and so threaten to alter radically the balance of power in the British Isles.

For anyone wanting a detailed narrative of the invasion, there are numerous chronicle accounts and modern retellings. 4 The record evidence is equally rich.

We are fortunate that the medieval English state was based on extremely solid recordkeeping foundations, of which The National Archives is the principal custodian. In the 13th century the Westminster model of government – Chancery (writing office), Exchequer (finance office), law courts and local administration (sheriffs, itinerant justices) – was translated to Dublin. The Dublin government enacted the English king’s laws, dispensed his justice and collected his revenues, but largely at one remove from the king. Ireland, too, was never fully settled; there remained large areas of native Irish power outside the authority of the king, some of whom looked to Bruce for aid to shed the ‘Norman yoke’. Communities on the margins increasingly exploited or circumvented English royal power as circumstance dictated.

Communication between Westminster and Dublin created masses of records: Irish government officials had to return to Westminster, for example, findings from inquisitions into lands held by deceased royal tenants; also, at regular intervals the Irish treasurer had his accounts audited in England. The value of these processes can best be seen in the survival of receipt and issue rolls of the Irish Exchequer (record series E 101). These are duplicate copies of those produced in Ireland, detailing monies received and spent on royal business – including raising and supplying armies – and deposited in the English Exchequer. 5 Their survival is all the more fortunate as the overwhelming bulk of record material for medieval Ireland, formerly held at the Public Record Office of Ireland (PROI), was lost in the destruction of that building in 1922 during the Irish Civil War. 6

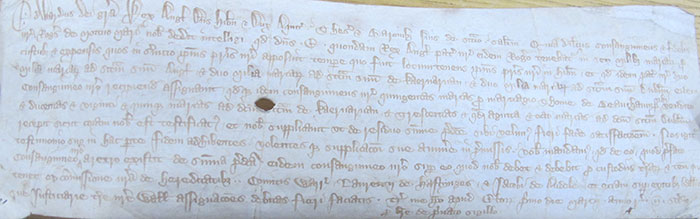

E 101/237/9, m. 1, Issue roll of the Irish Exchequer, 1318-20, showing a payment of £89 6s. 3d. to Roger Mortimer, the king’s lieutenant of Ireland, of the £400 granted to him for the sustenance of him and his men in the field

Within four months of landing, Edward Bruce had brought Ulster to heel. By the end of February 1316, he had converted early triumphs into a genuine threat to the security of the English lordship: following victory in battles at Kells in Meath in December 1315 and then early in the new year at Arscoll and Skerries in Kildare, Dublin itself lay vulnerable. The English royal government failed to assess the threat accurately and did not react quickly. Only in September 1315 had a special envoy, John of Hotham, a royal clerk, arrived with men, money and a mandate to reorganise the Dublin government to put it on a war footing. Ultimately, the Scots could not press their advantage due to heavy losses in battle and the scourge of famine, which now struck much of Europe following heavy rains. 7 Nevertheless, their southwards foray posed a severe psychological threat to the capital and from there the prospect of relatively easy communication with north Wales.

Over the summer of 1316 the English king and his barons descended into bitter personal rivalry. Meanwhile, the Scots in Ireland reached out to senior Welsh figures in the Principality, who were disaffected by the oppressive activities of English officials. In an exchange of correspondence, Edward Bruce addressed ‘all those [in Wales] desiring freedom’, stressing common bonds of kinship between the Welsh and the Scots. He offered to undertake a joint struggle, if the Welsh were to commit to him and grant him the chief lordship which their prince formerly exercised. 8 Around Christmas that year, King Robert himself arrived in Ireland with a large army of reinforcement. Despite the perils of a winter campaign the Bruce brothers surged southwards through Ireland, terrorising the citizens of Dublin, who panicked and burned some of their suburbs in self-defence.

By March 1317, the Scots had reached the Shannon in southwest Ireland. There is a very strong suspicion that King Robert was aiming to assist his brother give full force to his claims over the kingship of Ireland and therefore to establish Ireland as a satellite Scottish state.

When the English government roused itself, the response was extensive and coordinated to tackle the threats to Ireland and Wales. In the last quarter of 1316, Edward II shored up his garrisons on the northern border of England, restored a former chief governor of Wales – Roger Mortimer of Chirk – to his role, and named Chirk’s nephew, Roger Mortimer of Wigmore, as his Lieutenant in Ireland. Wigmore, himself the lord of the liberty of Trim northwest of Dublin, received an enormous fee of £4,000, which proved so difficult to raise in Ireland that he was still drawing it from the king’s wardrobe ten years later; his chief objective was to raise a force of 150 mounted men and 500 foot-soldiers and defeat and expel the Scots.

E 208/2/2, no. 421 Exchequer bill, 1327, ordering payment to Roger Mortimer of the sums outstanding on the £4,000 granted to him as lieutenant of Ireland

The expeditionary force landed in county Cork in early April 1317 and succeeded in pursuing the starving Scots northwards back to their Ulster base without toppling the English administration in Ireland. The lieutenant – a title only previously used for Edward’s notorious favourite Piers Gaveston in 1308 to 1309 – was able to bring the authority of personality and patronage to bear in reinforcing English lordship in Ireland. Record and chronicle evidence demonstrates that, over the next 18 months, the Dublin government used military force to cow rebels and native Irish leaders; however, they also negotiated hard across Ireland with warring family groups to bring them to peace, with a reasonable measure of success. Access to English law was also expanded to members of the native community who wished to enjoy it, too.

One of the most important aspects of the lieutenant’s activities was his attempt to redraw the landholding map in and around Dublin to the benefit of his own followers. Mortimer intruded English clients into manors and lands in counties Dublin and Meath in 1317 and 1318. Crucially, he also gave John de Bermingham, one of his main military advisers, a stake in county Louth closer to the border with Ulster. It was precisely these men with whom Edward Bruce clashed as he again marched southwards out of Ulster in the autumn of 1318 to meet his end at Faughart.

Faughart did not, of course, restore the military balance in Robert Bruce’s campaigns against Edward II: the Scots captured Berwick in April 1318 and remained on the front foot in northern England. But it remained one of the few English successes in arms of this most militarily unsuccessful reign. For this, Edward launched an investigation into the expenses incurred by Roger Mortimer in Ireland, who had acted ‘for the safety of the land and to repel rebels, and many have testified to his good service there’.

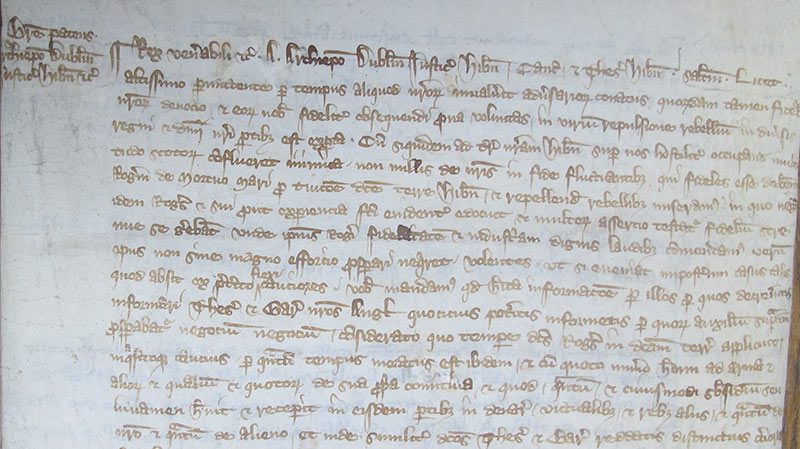

E 159/92, rot. 177, Memoranda roll 12 Edward II (1318-19), ordering the Treasurer of the Dublin Exchequer to investigate the costs of Roger Mortimer as the king’s lieutenant of Ireland

This stands in stark contrast to the view of the annals of Clonmacnoise abbey (Offaly) that Edward Bruce’s death brought ‘great joy and comfort to the kingdom in general … for there reigned scarcity of victuals, breach of promises, ill performances of covenants, and the loss of men and women throughout the whole realm’.

It would be one of the ironies of Edward’s turbulent reign that Mortimer – with whom he had shared such a close bond – would be the man to help bring about his unprecedented deposition in 1327. Ireland, moreover, remained an arena in which the Anglo-Scots struggle would be fought out, even after the new king Edward III acknowledged Scottish independence from England and asserted his overlordship… but I will leave that for future blog posts.

Notes:

- G O Sayles, ‘The Battle of Faughart, 1318’, in Seán Duffy (ed), Robert the Bruce’s Irish Wars The invasions of Ireland, 1306–29 (Stroud, 2002), 107–18 ↩

- R F Frame, The Political Development of the British Isles, 1100-1400 (Oxford, 1990); M Brown, Disunited Kingdoms: People and Politics in the British Isles, 1280-1460 (London, 2013) ↩

- The best recent account is Seán Duffy, ‘The Bruce Invasion of Ireland: a Revised Itinerary and Chronology’, in Robert the Bruce’s Irish Wars, pp 9-44 ↩

- R F Frame, ‘The Bruces in Ireland, 1315-1318’, Irish Historical Studies 19 (1974), 3-37, reprinted in his Ireland and Britain, 1170-1450 (London, 1998) The best medieval chronicle account, from a Scottish perspective, is John Barbour, The Bruce, ed AAM Duncan (Edinburgh, 1997) ↩

- The issue rolls have been published in English translation: P Connolly, Irish Exchequer Payments, 1270-1446 (Dublin, 1998) ↩

- For details on the Beyond 2022 project – which aims to recreate, virtually and intellectually, the PROI and its holdings before its destruction – see the blog post by my colleague Dr Neil Johnston. ↩

- Ian Kershaw, ‘The Great Famine and Agrarian Crisis in England, 1315–22’, Past & Present 59 (1973), 3–50 ↩

- J Beverley Smith, ‘Gruffudd Llwyd and the Celtic Alliance, 1315–18’, Bulletin Board of Celtic Studies, xxvi, part 4 (May 1974–6), 463–78, pp 471; idem, ‘Edward II and the allegiance of Wales’, passim ↩

Excellent, very informative