The National Archives recently announced that we are going to be loaning our earliest public record, Domesday Book, to the British Library for the Library’s forthcoming Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms exhibition. You can also see this iconic document in the first episode of ‘Cunk on Britain‘, the new series on BBC2.

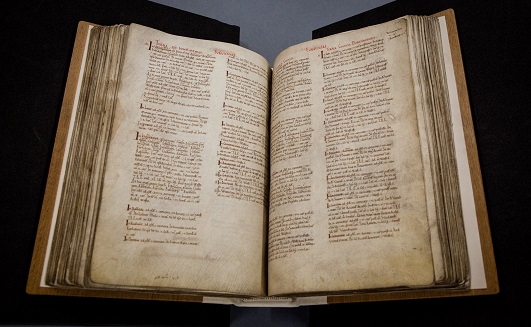

The Domesday survey was commissioned by William the Conqueror at Christmas in 1085, nearly 20 years after his Conquest of England. It was an enormous, incredibly detailed survey of land and landholding in his new kingdom, and it is this survey that was written up into the volumes that are preserved today at The National Archives. Domesday records in extraordinary detail, county by county, who held land and what resources were available from it – its taxable value, numbers of livestock, details of arable land, quarries, water mills, fisheries and more, as well as some information about the people who lived on the land.

Great Domesday open at folios for Yorkshire (E 31/2/2).

Not only did Domesday record the situation in 1086, it also recorded details of the same lands before the Conquest, and at the time of Conquest. Because of this, it gives us a unique window through which we can see the medieval world and the enormous changes brought about in English society, politics and economics by the Norman Conquest.

In fact there is more than one ‘Domesday’. The National Archives holds Great Domesday, which covers most of the ancient English counties, and Little Domesday, which includes Suffolk, Norfolk and Essex. It is generally believed that Little Domesday forms part of an earlier stage of the writing-up process of the survey returns, which for some reason (perhaps the death of William the Conqueror in 1087) was never written up into the final version, Great Domesday. Great and Little Domesday were themselves divided into parts in 1986 as part of conservation work. 1 There are now two volumes of Great Domesday (one of which is being loaned to the British Library) and three of Little Domesday. There is also related material held at other archives, such as the Exon Domesday held at Exeter Cathedral. 2

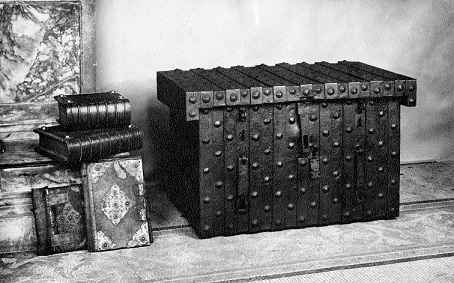

The Domesday Chest (E 31/4) with Domesday in 1949.

Domesday as a document has had an amazing history. 3 It was originally kept at the royal treasury at Winchester, but from about the mid-13th century it was moved to the Treasury of the Receipt of the Exchequer at Westminster, a sort of treasure house of important documents. From around 1600, Domesday was kept in a large, iron-clad wooden chest which had three different locks. The key to each lock was held by a different official, so that it could only be opened with the consent of all three of them! The chest is still kept at The National Archives, although it no longer houses Domesday.

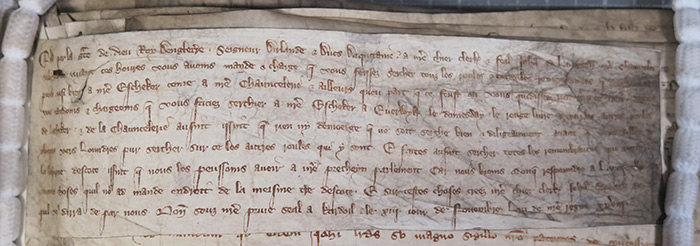

A writ of Edward I from November 1300, showing that Domesday was at York (C 81/22/2207)

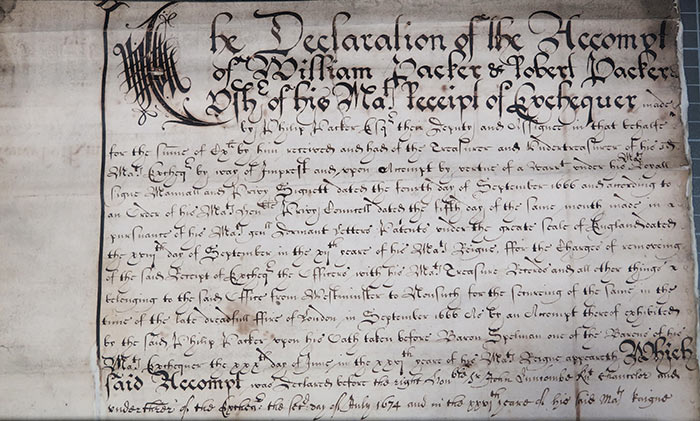

Although Domesday had a permanent home at Westminster, it did still travel occasionally. Medieval kings travelled a great deal around the kingdom, and there is evidence that, on occasion, Domesday (and other treasured documents) went with them. During the plague years in the reign of Elizabeth I, Domesday accompanied Exchequer officials who relocated temporarily to Hertford. And in September 1666 it was taken to Nonsuch to escape the Great Fire of London. Fire was again a menace in 1834, when much of the Palace of Westminster was engulfed in flames. The fire was caused by the burning of wooden tallies, notched pieces of wood that had been used in historical accounting procedures. Domesday was being kept in the Chapter House, and the keeper of the Chapter House, the historian and scholar Sir Francis Palgrave, asked the Dean of Westminster to be allowed to move Domesday and other historical records to the Abbey for safekeeping. Astonishingly, the Dean refused, saying that he first needed a warrant from the Prime Minister, Lord Melbourne. Fortunately the fire did not spread to the Chapter House and Domesday survived.

An accounting roll for the removal of the ‘Receipt of the Exchequer’ to Nonsuch because of the ‘late dreadful fire’ (AO 1/865/1).

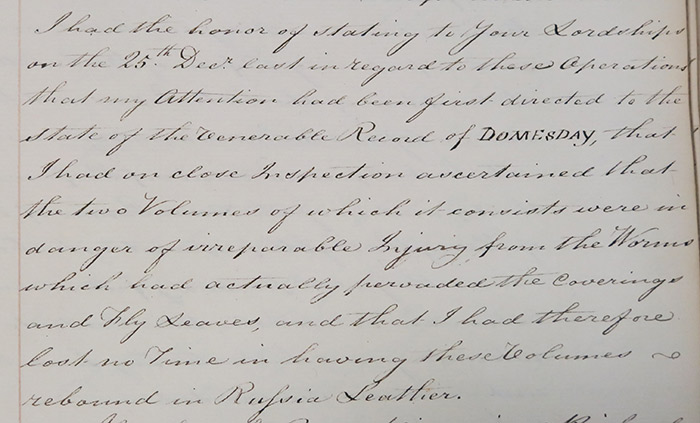

This appalling fire was one of the factors used to promote the foundation of a new Public Record Office – an institution where government records could be brought together from the various places where they were stored, and kept safely and securely, with their conditions carefully monitored. This was certainly necessary for Domesday: a report to the Royal Commission on Public Records in the early 19th century states that Domesday had to be rebound as the wooden boards which protected it were being attacked by woodworm. The Public Record Office (PRO) was eventually founded in 1838, and Domesday moved in in 1859. (We can also note that the tallies which survived the Westminster conflagration were later also transferred to the new PRO where they could cause no further harm!)

Report on the rebinding of Domesday in 1819 due to danger from worms (PRO 36/7, p.237).

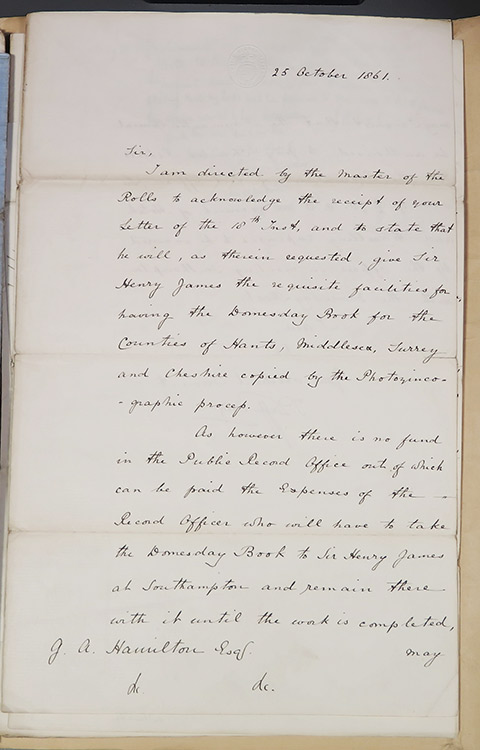

One might think that its arrival at the PRO would have put an end to Domesday’s peregrinations. But this was not quite the case. In the late 1850s the head of the Ordnance Survey Department, Sir Henry James, had developed a new photographic technique called photozincography and was determined to prove its worth by reproducing medieval documents. In 1861 he was able to convince the various officials with responsibility for Domesday, including the aforementioned Sir Francis Palgrave (by now Deputy Keeper of the PRO) to allow him to reproduce it using his new technique. This involved disbinding Domesday and taking it, a few counties at a time, to Southampton, where the folios were photozincographed in the open air on the South Downs. By 1863, the whole of Great and Little Domesday had been reproduced in this way. The whole enterprise was extremely expensive, and documents held at The National Archives include all sorts of wrangling about which government departments should pay for what. The project was supported throughout by the raising of subscriptions and by the sale of the bound volumes of the reproductions. Although taking this ancient record onto the South Downs for this escapade sounds rather reckless to us, the resulting photozincograph edition was a great achievement, and did much to bring Domesday to wider public attention. 4

Part of a letter from Thomas Duffus Hardy about the photozincographing of Domesday, 1861 (T1/6332A/17908).

By March 1864, Great and Little Domesday were back at the PRO, although they were not rebound for several years due to considerable disagreement about what their new covering ought to look like. Domesday’s next major upheaval came with the First World War. With London not considered a safe place, Domesday – along with a number of other records – was transferred to a new temporary store at Bodmin Prison on Dartmoor. During the Second World War, large numbers of records were again evacuated – this time to Shepton Mallet Prison in Somerset. It was a wise decision: part of the PRO building was destroyed during the Blitz in 1940.

In 1977, after over a century at Chancery Lane, Domesday was moved to the new PRO building at Kew, where it still lives. It celebrated its 900th birthday with further rebinding work, when it was also photographed to produce a high-quality facsimile edition. 5 Now more than 900 years old, Domesday is extremely fragile and here at Kew it is kept in carefully controlled conditions, monitored by our expert staff. While the contents of Domesday can be explored both online and in numerous printed books, we nonetheless recognise how important it is for the public to be able to engage with this iconic document itself. So we are delighted to be loaning it to the British Library for their forthcoming Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms exhibition.

For further details of the exhibition, please see the British Library website.

Notes:

- For this work, please see Helen Forde, ‘Domesday Preserved’ (London, 1986), available in The National Archives’ Library. ↩

- There is an enormous literature on the writing, purposes and use of Domesday and its related texts, some of which is available in The National Archives’ Library and our Bookshop. There is also further information and a select bibliography in our Domesday research guide. ↩

- For full discussion of Domesday’s long and fascinating history, please see E Hallam ‘Domesday Book: Through Nine Centuries’ (London, 1986), available in The National Archives’ Library. ↩

- These reproductions are available in The National Archives’ Library. ↩

- The printed facsimile editions are available at The National Archives and images of individual folios can be downloaded from the website. See the research guide for more details. ↩

The Domesday book needs copying into Excel, as people can then search it by using Filters on regions and names.

This would then be used by schools as we could teach how to filter it be regions, towns and names.

Perhaps History graduates could be the task of translating the old English into Excel for a specific region with surnames within a set range eg A-C’s.