It’s Tudor Week on the Great British Bake Off tonight! Who will lose their head, and who will rise to the occasion?

To mark the event, I wanted to celebrate some of the varied and more unusual delicacies which would have been eaten and enjoyed in the 16th century by Henry VIII, Elizabeth I and the rest of the royal court. In order to do this, I have delved into our vast collection of administrative and royal documents, to find examples of Tudor food and feasting which might inspire tonight’s bakers.

For their signature bake, the contestants will present Mary Berry and Paul Hollywood with their own take on a Tudor pie. Pies and pasties were a popular food product in medieval and Tudor times, and they feature frequently in some of the private correspondence held in our collection. Pies provided a convenient way to preserve meat for a short period of time, and were relatively durable, with a thick crust. They were also handy as a type of self-contained fast food (not requiring the use of a plate) and were filled with a wide variety of fillings including partridge, venison, cod, carp and lampreys (as seen in the entry below).

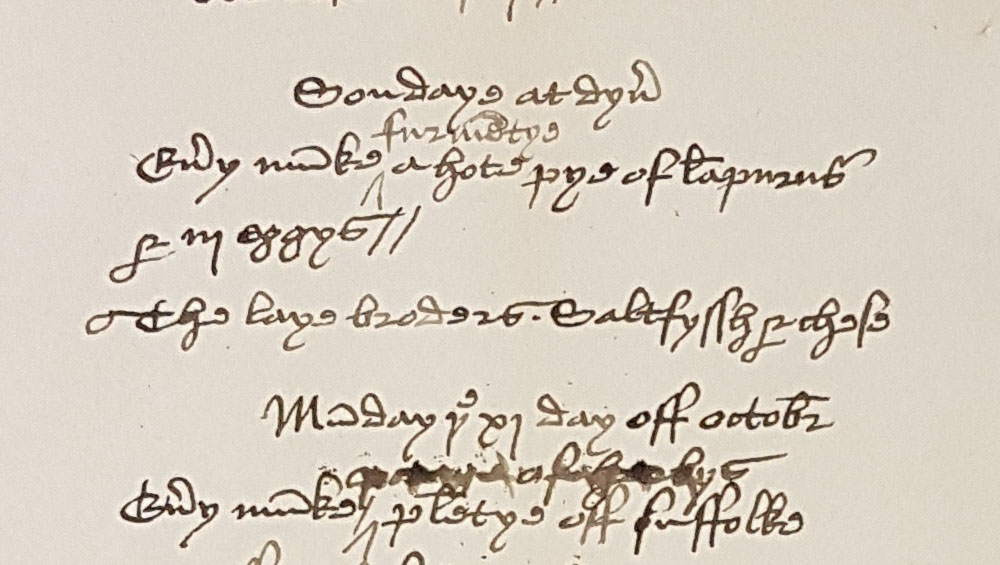

Allowance for meals at the London Charterhouse in 1535. Each monk was given a hot lamprey pie for his dinner this Sunday, along with three eggs. The lay brothers (secular men who lived in the Charterhouse, but were not monks) were given bread, stockfish (a type of dried fish), and cheese instead (catalogue reference: SP 1/97, f. 162)

Pies, pasties and other rich foods were often given as gifts amongst the Tudor elite. The Lisle Papers are a rich source of information about Tudor Life.[ref]1. These papers contain the correspondence of Arthur Plantagenet, 1st Viscount Lisle (c.1480-1532), an illegitimate son of Edward IV (and thus Henry VIII’s uncle), and of his wife, Honor Plantagenet.[/ref] They are stuffed full of references to pies and other gifts of food.

Food was clearly important to the Lisles, as they regularly sent each other gifts of food, including baked cranes, wild boar pasties, marmalade, quails and partridges. In 1539 Lady Lisle wrote to her husband, sending him several partridge pasties along with a toothpick: a gift for the use of a German prince who had recently stayed with the family. Lady Lisle had been concerned that the German was wont to pick at his teeth with a pin after eating, and so she felt compelled to send him her own toothpick, which had seen several years of use!

To impress Mary and Paul with their pies, the bakers will have to pull out all the stops, and hope that nothing goes wrong. The temperamental nature of baking pies, however, is nothing new. Who knows if Paul will imitate the style of Lisle’s business agent, John Husee, who in 1537 criticised a batch of venison pasties which he had received on behalf of Lisle, complaining that:

‘Harold’s wife caused them to be baken; but as she shewed me, it is baken without lard’![ref]2. Catalogue reference: SP 3/5, f.58[/ref]

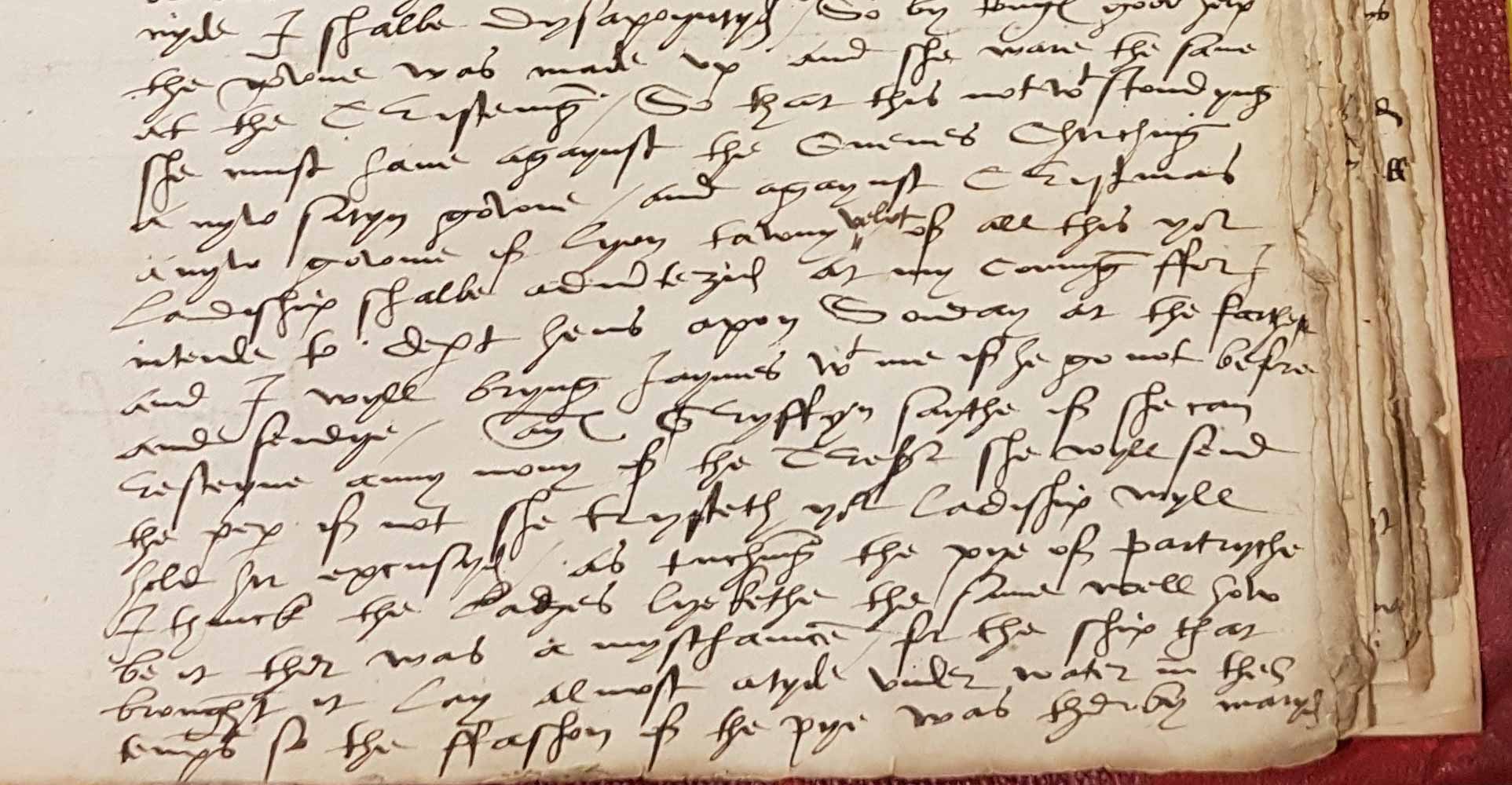

Cooking the pasties without lard would presumably have left them dry and unappetising, a warning that the bakers would do well to heed when producing their own pies. Even once a pie was baked, problems could occur in transportation. One partridge pie, sent to Husee in 1537, was damaged when the boat transporting it began to sink, until it ‘lay almost a tide underwater in this Thames, so that the fashion of the pie was thereby marred’. It is not recorded whether this accident also resulted in the pie having a ‘soggy bottom’, although it seems likely!

Account of the near loss of a partridge pie. The final line reads ‘so the ffashon of the pye was therby maryd’ (catalogue reference: SP 3/12, f. 110)

Perhaps the bakers can take some glimmer of hope from the fact that, even after this setback, it was reported that the two girls who ate the pie (Tudor ancestors of Mel and Sue?) found it to be tasty, and the pie was pronounced a success. Proving that even a drowned pie can be saved, provided it was a good bake in the first instance!

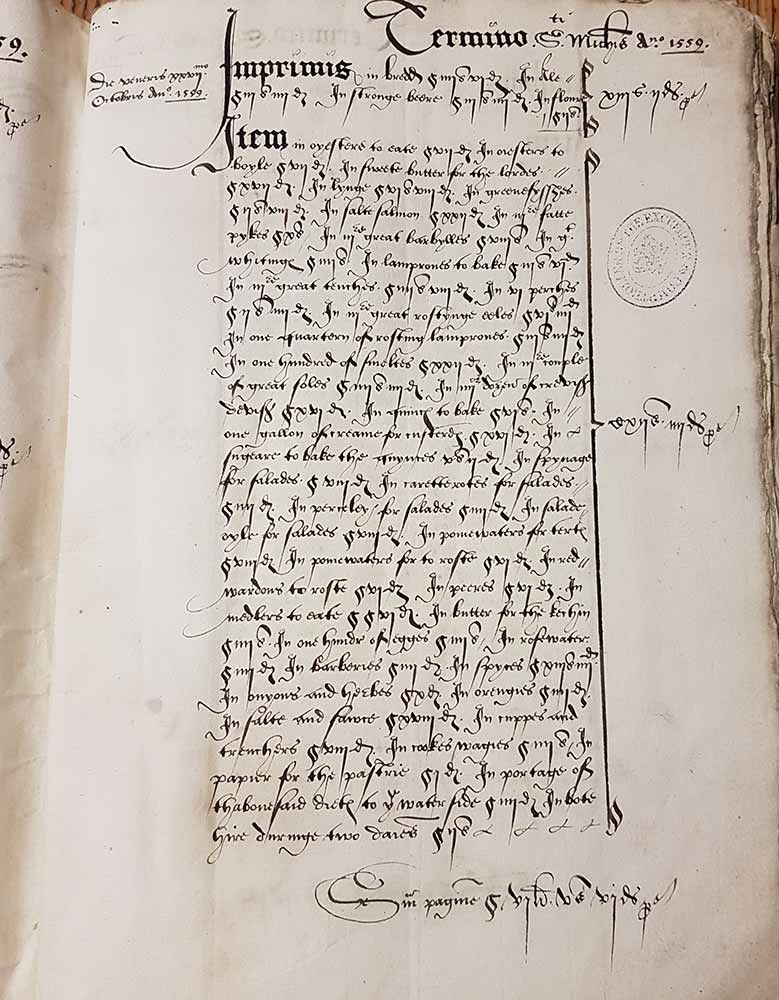

Besides pies and pasties, there are numerous other types of Tudor food and drink found within our collection, including menus, diets and recipes. Tudor monarchs were obliged to provide meals for their councils and household, the details of which were recorded in diet books. These books record a wide variety of the varied diet consumed by the Tudor elite of the Queen’s Star Chamber.

Some of the staples of the privy council’s diet included bread, ale, strong beer and flour, to which were added fish, salad and desserts, all cooked and baked in different ways. Fat pykes, great roasting eels, roasted lampreys and 100 smelts were all accounted for, to be served with a salad of spinach, parsley, carrots and ‘salade oyle’.

Diet of the Privy Council, October 1559 (catalogue reference: E 407/54)

Perhaps of most interest to the bakers facing Mary and Paul are desserts. Apples, oranges, pears and medlars (a small fruit which wasn’t eaten until it was half-rotted) were all purchased for the council to eat – both raw and roasted. Some of the sweet apples (known as pomewaters) were used to make an apple tart. Accompanying the tart was roasted quince and custard, for which a gallon of cream purchased, along with 100 eggs!

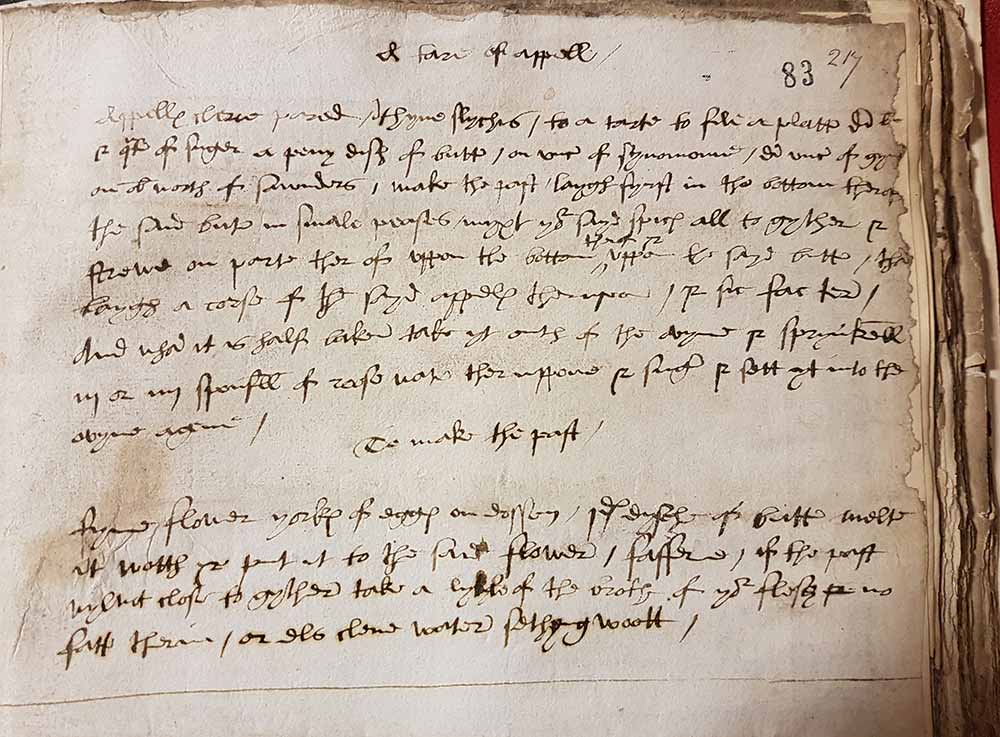

This apple tart is of particular interest, as I’ve recently located a near-contemporary recipe for Tudor apple tart here in the archives. I’ve included the recipe below for any bakers who want to try their hand at their own Tudor tart. It even includes some tips, suggesting the addition of extra fat or hot water if the pastry does not form. Interestingly the recipe was located in a collection of ecclesiastical tracts from the Reformation (surrounded by theological sermons) proving that even in Tudor times, a good tart recipe could be considered heavenly!

Enjoy Tudor Week tonight. Let’s see how far the bakers will go in their use of weird and wonderful ingredients in order to become Star [Chamber] Baker, and who will lose their head!

Henry VIII’s tart[ref]3. Catalogue reference: SP 6/6, f. 109[/ref]

A fare of apple

Clean apples, pared thinly sliced [for a] tart to fill a platter.

Take half [ingredient lost due to manuscript damage], a quarter of sugar, a penny dish of butter, an ounce of cinnamon, half an ounce of ginger, a halfpenny worth of pomace.[ref]4. The solid remains left behind after pressing fruit such as grapes or apples.[/ref]

Make the past[ry] laying first in the bottom thereof …[manuscript damage], the said butter in small pieces.

Mix your said spices altogether and strew one part thereof upon the bottom thereof, and upon the said butter.

Then lay a course of the said apples thereupon et sic fac ter [and do this three times].

And when it is half baked, take it out of the oven, and sprinkle three or four spoonfuls of rose water thereupon, and sugar, and put it into the oven again.

To make the past[ry]

[Take] fine flour, yolks of one dozen eggs, 1d. [penny] dish of butter melted well and put into the said flour.

If the past[ry] will not close together of the broth of your flesh, put new fat therein or else clean water, seething well.

Tudor apple tart recipe. You can find a slightly modernised version above if you want to try your hand at baking your own Tudor tart! (catalogue reference: SP 6/6, f. 109)

[…] techadmin on October 12, 2016 The dissolution of the pasties: GBBO’S Tudor Week2016-10-12T08:30:31+00:00 – Journals & Publications – No […]