With 2018 marking the centenary of the Armistice, a host of public and cultural events will take place next year to commemorate the end of the First World War.

Yet, for many Great War veterans, the impact of the war continued long after the guns fell silent. In comparison to the British serviceman’s experience at the Front, public knowledge of the post-1918 experiences of disabled veterans remains comparatively unfamiliar.

In the years following the cessation of the First World War, over one million ex-servicemen received a disability pension from the Ministry of Pensions, which varied in scale and accordance with the type and severity of disability.

Disabled veterans were also provided with opportunities to undertake employment training and medical treatment in exclusive institutions. In comparison to those who returned to civil society who were, initially at least, able to benefit from such initiatives, efforts to compensate Great War veterans who experienced mental health problems remained minor and tokenistic.

In comparison to mental health services available today, there was little expectation of recovery once a Great War veteran was institutionalised. Containment, rather than cure, remained the focus of district asylum care. In an attempt to prevent the Great War veterans who suffered mental health problems from being tainted with the stigma of pauper lunacy, the Ministry of Pensions funded the ‘Service Patient’ scheme throughout British asylums from the summer of 1917.

The scheme enabled ex-servicemen to be dressed in private clothing, receive a small weekly allowance of pocket money, and be buried outside the asylum walls (and spared a pauper’s grave) if a man died while under treatment.

In 1922, county and borough asylums throughout England and Wales hosted almost 5,000 Service Patients. The population of each asylum correlated with regional enlistment figures with asylums near densely-populated urban areas accommodating the bulk of veterans.

Despite the scheme being launched to prevent ex-servicemen being treated akin to pauper patients, the practicality of this ambition remains doubtful.

The stigma of mental health problems was seemingly not avoided. For example, due to public dissent over the lack of segregation between mentally ill veterans and general patients, two Ministry of Pensions hospitals dedicated to ‘the hopeful type’ were founded in the mid-1920s.

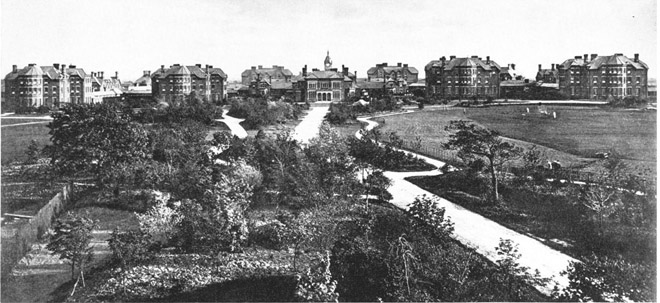

Whittingham Asylum, Preston, Lancashire

Previous research into one of the facilities, established in an annexed building on asylum grounds, has revealed that these facilities largely operated along asylum lines with ex-servicemen having scarce opportunity for recovery and discharge. The hospital was closed in 1931 with the remaining patients subsequently transferred back to public institutions.

From the outset of the Service Patient scheme, the Ministry of Pensions rejected institutions whose upkeep of private patients was deemed to be too expensive.

Thus, Service Patients shared asylums with the wider patient population with negligible segregation beyond being differentiated in clothing during leisure time.

The conditions, infrastructure and quality of care on offer during this period varied widely on an institutional basis. Rather than a man’s mental ill health being attributed to war service, the most important issue which dictated a Service Patient’s experience of institutional life remained his location and the asylum he was subsequently eligible to be admitted.

Further Reading

Peter Barham, Forgotten Lunatics of the Great War (New Haven, 2004).

Fiona Reid, Broken Men: Shell Shock, Treatment and Recovery in Britain, 1914-1930 (London, 2010).

Alice Brumby, ‘A Painful and Disagreeable Position’: Rediscovering Patient Narratives and Evaluating the Difference between Policy and Experience for Institutionalized Veterans with Mental Disabilities, 1924–1931’ in First World War Studies, vol. 6 (2015), pp 37-55.

Dr Michael Robinson is a Wellcome Trust funded Early Career Researcher located at the University of Liverpool’s History Department. He will be speaking at The National Archives on Thursday 22 March 2018.

I am seeking information on RICHARD GREGORY ISAAC DALLAS.AKA HUNT/BARNETT.b.November 20 1872.He served in a variety of regiments.

The First World War did not end on 11 November 1918, it was just an Armistice and the Germans started fighting over the ‘War Guilt’ clause in what became the Versailles Peace Treaty of 1 July 1919. In fact many war memorials have the correct date of 1914-1919, the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, I believe, uses 1921 and Government used 1922 or 1923.

I agree with the previous comment about the Great War not ending with the Armistice in 1918.

Educating the general public of this is very difficult, as most War Memorials have the dates 1914-1918 on them.

The date of 1919 is interesting, as my Grandfather, who was in the Machine Gun Corps during WW1, has his end of service date as 1919 in his official service records, which has always confused me. Could this be the explanation for this?

I worked for the Ministry of (war) Pensions from 1947 until 1953 and part of that time was spent in administering the pensions and allowances of ex forces personnel who were in various hospitals and institutions because of physical injury or mental incapacity. My own impressions were that despite the sadness of the situation some effort was made to give the men and their families a modicum relief.

Looking for Outrage file ‘re war of independance Ireland 1919/1921

I also agree with the later date of 1919 when my father returned from India having fought and been shot in battle in Mesopotamia with the Hampshire Regiment during their deployment there from 1914.