The National Archives holds detailed records of people in some areas of public service - notably the armed forces – but remarkably little about civil servants. The surviving records are patchy, and very varied in nature, rarely containing information beyond dates, grades and, occasionally, salaries. But digging deeper into a department’s internal records and correspondence can sometimes reveal much more personal information.

The General Register Office (GRO), established in 1836, occasionally made lists of its staff: these appear in a variety of documents, although they give little more than the most basic facts. But detailed registers of correspondence with the Treasury were kept dealing with many subjects, from the administration of the registration service throughout the country to staff welfare and discipline within the GRO’s Somerset House headquarters.

There is a great deal about both major and minor misdemeanours by staff, their health and financial problems, and the day-to-day details of running a busy public service. A number of staff suffered ill-health which was caused by, or exacerbated by, the nature of their work – life could be very hard for the Victorian clerk, with little or no pension provision and no welfare safety-net. But these Treasury letter-books also describe one long-serving and valued member of staff as ‘deaf and dumb’.

Charles Hazard was employed from 1844 to 1872; he began as a junior clerk, later progressing to senior clerk, in the Records Section, which dealt with the collating and indexing of records of births, marriages and deaths. When he died in 1872, the Registrar-General said of him, ‘He was deaf and dumb but well educated, and he performed all duties assigned to him in a creditable and satisfactory manner, proving himself, during the 28 years I have known him employed in this office, a valuable Civil Servant of Her Majesty.’

Charles Hazard may have been well-educated, but nowhere near the level of his two younger brothers, William and Thomas. Like their father, they both became solicitors, William in their native Norfolk and Thomas in London. Both of them appear in electoral registers as owners of freehold land; when they died, the values of their estates were £76,000 and £6,000 respectively, while Charles left under £1,500. All three, however, were described as ‘gentlemen’. Charles never married, and the only time he appears in the census with any member of his family is in 1871, when he is aged 44, and is with his brother Thomas. In the infirmity column it is stated that he had been deaf and dumb from birth. Even in 1841, when he would have been only 14 years old, he was neither at home with his widowed father, William, in Harleston in Norfolk, nor with his two brothers who were at school nearby. When William died in 1857, his two younger sons were executors, and while provision is made for Charles, it is in the form of a life income from dividends. (PROB 11/2246/154)

But Charles was not the only GRO clerk who was deaf and dumb. His near contemporary, Florance Fox, joined in 1841, and worked there for 33 years until his superannuation in 1874. Like Charles Hazard, he was a junior clerk, and then a senior clerk, in the Records Section. The information that he was ‘deaf and dumb’ comes from the census, where he is so described in 1851, 1861 and 1871. The description is quite specific, since his wife, Caroline, is shown in each census as ‘deaf’, and in 1861 this is qualified with ‘but not dumb’. This census also provides the detail that Florance had been deaf and dumb from the age of four. The census itself had only the single category ‘deaf and dumb’ to classify anyone without hearing, until 1911 when a distinction was made between ‘Totally deaf’ and ‘Deaf and dumb’. The fact that Florance and his wife were described differently in 1861 shows not only that there was considered a distinction between the two, but that the enumerator felt it was worth recording when he copied the details into his enumeration book.

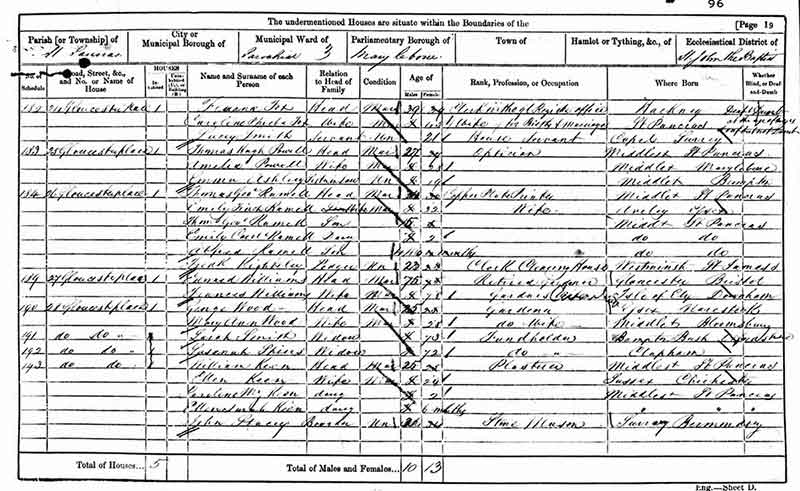

RG 9/120 folio 96 page 19: page from the 1861 census showing the entry for Florance and Caroline Fox.

His distinctive forename came from his mother’s maiden name, and this was not the only unusual feature of his family. His father, William Johnson Fox, came from a modest farming background, but became a Unitarian minister and preacher, and later a Liberal MP associated with radical causes. His sister, Eliza, was a portrait painter and his brother, Franklin, became a master mariner. They were by no means as prosperous as the Hazard family, but as a preacher, politician and writer, William Johnson Fox was an influential figure. Like Charles Hazard, Florance Fox was clearly educated to a good standard, which was by no mean the case for most deaf children in 19th century Britain. There was little specialist provision, beyond some charitable institutions, and many people did not consider that the deaf could be educated at all. The families would have had to seek out suitable teachers for their sons, which many others would not have done. It may be that it was at such an establishment that Florance Fox met his wife, but in the absence of any official records it is unlikely that we will ever find out.

We can’t know for certain how they came to be employed as GRO clerks, but is likely that it was through the influence of their families, who were both well-connected in their different ways. It was not unknown for requests to be made for the employment of relatives: a Treasury Letter Book records that in 1854 William Bayley, a porter in the GRO, asked if a post could be found for his son, who had been educated at the London Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb. Sadly, there is no trace of his ever joining the service.

Very interesting, it is ironic that as you say that there are few files about civil servants.

Thank you for that interesting human story.

This is what social and family history is all about, marrying info from different sources to create a bigger picture.