‘…so ought not this event in any history to be forgotten. Then it is well that I tell it to you!’ 1

This noteworthy historical event described by the Black Prince’s biographer was in fact the little known attempt by French forces during the Hundred Years War to recapture the English held town of Calais by means of bribery and subterfuge.

Calais was only a recently won prize for King Edward III, who had paid a high price in military and financial resources to secure its surrender in August 1347.

Thus, a French re-conquest of Calais barely two-and-a-half years later in 1350 would be catastrophic both for Edward’s military prestige and launching future English military campaigns in France.

How this event played out and how Edward and his eldest son prevented an embarrassing strategic reversal reads like something out of a special operations mission!

The French attempt to recapture Calais from England on 1/2 January 1350 in the Chronicle of Jean Froissart. Note the man on the drawbridge wearing the green and red cape with gold trimming receiving a sack of money. He is one of the central characters in this story. (source: Wikicommons)

It was Geoffrey de Charny, the battle-hardened commander of France’s north eastern frontier with Calais and Flanders, who first conceived of a plan to seize Calais right under English noses and overturn France’s humiliation suffered two years before.

Charny, through his spies, had identified an Italian from Lombardy by the name of Aimeric of Pavia amongst the English garrison who might be persuaded to betray the town to France… at least for the right price!

The choice was not without reason as Aimeric, firstly, was not an Englishman and was a mercenary by trade. Indeed, some chroniclers assert that the Lombard had previously served on Genoese galleys hired by the French crown.

He also evidently came to play an important role in the defence of the town. Administrative records held at The National Archives indicate that Aimeric’s maritime expertise had been recognised by Edward, who granted him a house in the town (Calendar Patent Rolls Edward III vol.7, p.565) and appointed him captain of the King’s galleys, the Thomas of Calais.

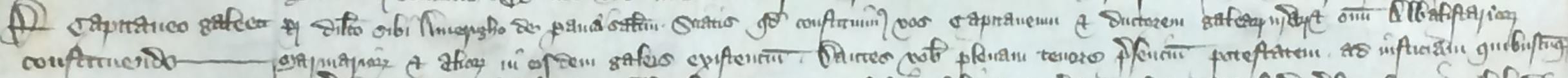

Appointment of Aimeric of Pavia as captain of the King’s galleys commanding all crossbowmen, mariners and others within the said galleys, 28 April 1348 (catalogue reference: C 76/26 m.16)

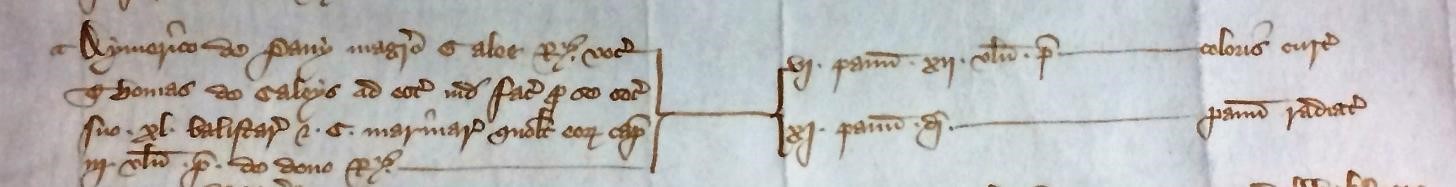

A roll of royal liveries (garments made for the King, his household and royal officials) confirms Aimeric was master of The Thomas of Calais, a galley with a sizable crew. All were provided with capes of short coloured and striped cloth.

The entry in Livery Roll records that a total of six pieces and 12 ells of short coloured cloth and 11 ½ pieces of striped cloth would be required for Aimeric and the crew of the Thomas of Calais (catalogue reference: E 101/391/15 m.23)

Charny believing the lure of gold would be enough to change the Italian’s loyalties sent an agent to meet Aimeric in secret.

His instincts appeared to be right.

In exchange for the substantial sum of 20,000 French crowns (approximately £25,000 or £10.7 million today) the Lombard agreed to admit a small French force into the Calais fortress, under cover of darkness. Once admitted, the French raiding party would creep through the town to the southern gate without alerting the garrison, which would be opened to Charny’s 5,000 strong army.

Somehow King Edward discovered the plot whilst celebrating Christmas at Havering. Though it is not stated how, it is plausible that Aimeric double-crossed Charny and informed Edward.

Shortly after the failed French attempt to retake Calais, Edward granted Aimeric a generous annuity of £160 for life for his service. Had the Lombard’s duplicitous actions been discovered by another source and denounced as treachery, Edward would have most likely had him hanged rather than rewarded him.

Certainly, the English King would not have involved his Italian galley master as he did in what he planned to do to save Calais had he cause to question his loyalty.

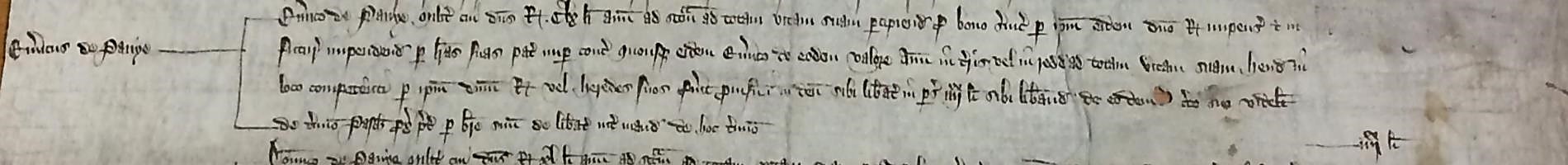

Entry in the Issue Rolls of £80 paid to Aimeric de Pavia (‘Emericus de Pavye’) as part payment of a lifelong annuity for good service of £160, dated 9 April 1350 (catalogue reference: E 403/353 m.1)

Edward therefore decided to launch his own clandestine military operation. A few days later, on 30 December 1349, the King, accompanied by his eldest son Edward Black Prince and a small force including his household troops, travelled to Calais in disguise.

How Edward managed to conceal his arrival is not clear but the chronicler, Froissart, suggests that Edward may have been using the banner of the reputable soldier and royal ambassador in his service, Sir Walter Mauny [Manny]. 2

Upon arrival, Edward in the words of one English chronicler, ‘prepared a crafty welcome for the French.’ The French ruse would be allowed to unfold with the initial French force allowed to pass into the citadel.

They would, however, be walking straight into an ambush as soldiers of Edward’s household were hidden within cellars, vaults and chambers within the castle.

According to one chronicler, Edward ordered the construction of a new wall behind which troops were concealed. One of the great beams of the castle drawbridge was also to be partially sawn through and upon a given signal would be broken by a stone dropped from the tower above. 3

On the night of 1 January 1350, an advanced party of around 100 French troops led by one of Charny’s deputies, Oudart de Renti, who also carried a sack of 20,000 French crowns on his person, crept towards the fortress to rendezvous with Aimeric.

After collecting his money, Aimeric led the Frenchmen into the citadel as agreed. The trap was sprung!

Renti and his men were set upon by concealed English forces and promptly surrendered.

Meanwhile, Charny had assembled his main force close to Calais’ southern Boulogne gate waiting for it to be opened. Yet as dawn broke over Calais and the portcullis was raised, it was not Renti that greeted the French commander but cries of ‘Edward, St George!’ shouted by a charging body of English knights and archers led by King Edward himself!

Half of Charny’s force broke before the initial attack but the veteran commander rallied his remaining troops and might have overwhelmed Edward’s outnumbered force had it not been for the timely arrival of his son with troops sallying from Calais’ northern gate.

Charny and other junior French commanders were taken prisoner and his remaining troops now either fugitives or corpses. In a chivalrous gesture no doubt embellished by contemporary chroniclers, Edward invited his prisoners as honoured guests to a banquet that evening.

In an act of special courtesy Edward is said to have commended the courage of the French knight, Eustace de Ribbemont, whom he had fought hand to hand with and in recognition given him a circlet garnished with pearls. 4

The King’s standard bearer, Sir Guy de Brian, was also singled out for reward for his role in the battle, being granted an annual pension of 200 marks (approximately £133). The record below provides a rare ‘citation’ commending Sir Guy for his conduct ‘in the last conflict between the King and his enemies of France at Calais for bearing the king’s banner against those enemies prudently and also keeping it uplifted strenuously and ably.’

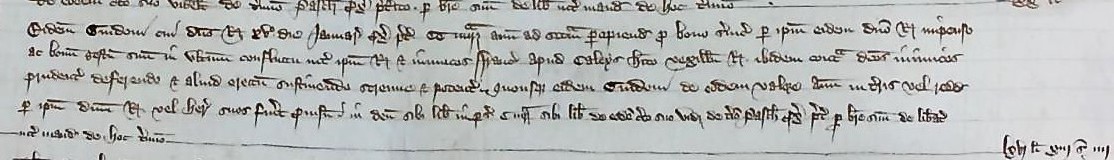

Entry in the Issue Rolls of a payment of £66 13 shillings 4 pence as part payment of an annuity of 200 marks granted to Guy de Brian for keeping the King’s standards raised during fighting at Calais, dated 19th April 1350 (catalogue reference: E 403/353 m.3)

Unfortunately, things did not fare so well for Aimeric. Two years later the French took possession of the outlying English castle of Fretun and captured Aimeric, who was castle governor at the time.

The French commander that ordered the attack was none other than Geoffrey de Charny, who had recently been released from English captivity and had the double-crossing Lombard promptly executed!

Nevertheless Edward’s covert military gamble had been a triumph. Not only had a French recapture of Calais been prevented, but Edward’s astute military leadership had ensured Calais remained under English control for the next 200 years.

Exchequer Seal for Calais, reign of Richard II (catalogue reference: C 109/87/1)

Notes:

- Chandos Herald, The Black Prince, ed. and trans. Francisque-Michel (London, 1883), lines 453-455, p.29 ↩

- Chronicle of Jean Froissart ed. and trans. T Johnes, rev. ed. (New York, 1901), vol. 1. pp. 47-48 ↩

- Extract from Chronicle of Geoffrey le Baker, Life and campaigns of the Black Prince, ed. and trans. Richard Barber (Woodbridge, 1986) pp. 45-48 ↩

- Froissart, Chronicle, 1. p.49 ↩