In 2013 the government began its move towards releasing records when they are 20 years old, instead of 30. Two years’ worth of government records will be transferred to us each year until 2022. We receive records from government throughout the year (which you can find by using the record release date options in Discovery, our catalogue’s advanced search) but a highlight of the year is the release of Prime Minister’s Office and Cabinet files. These files give us a fascinating insight into decisions taken at the very top of government.

This year we released a tranche of files from 1991 and 1992, the early years of John Major’s time as Prime Minister, with some files stretching back into Margaret Thatcher’s term of office.

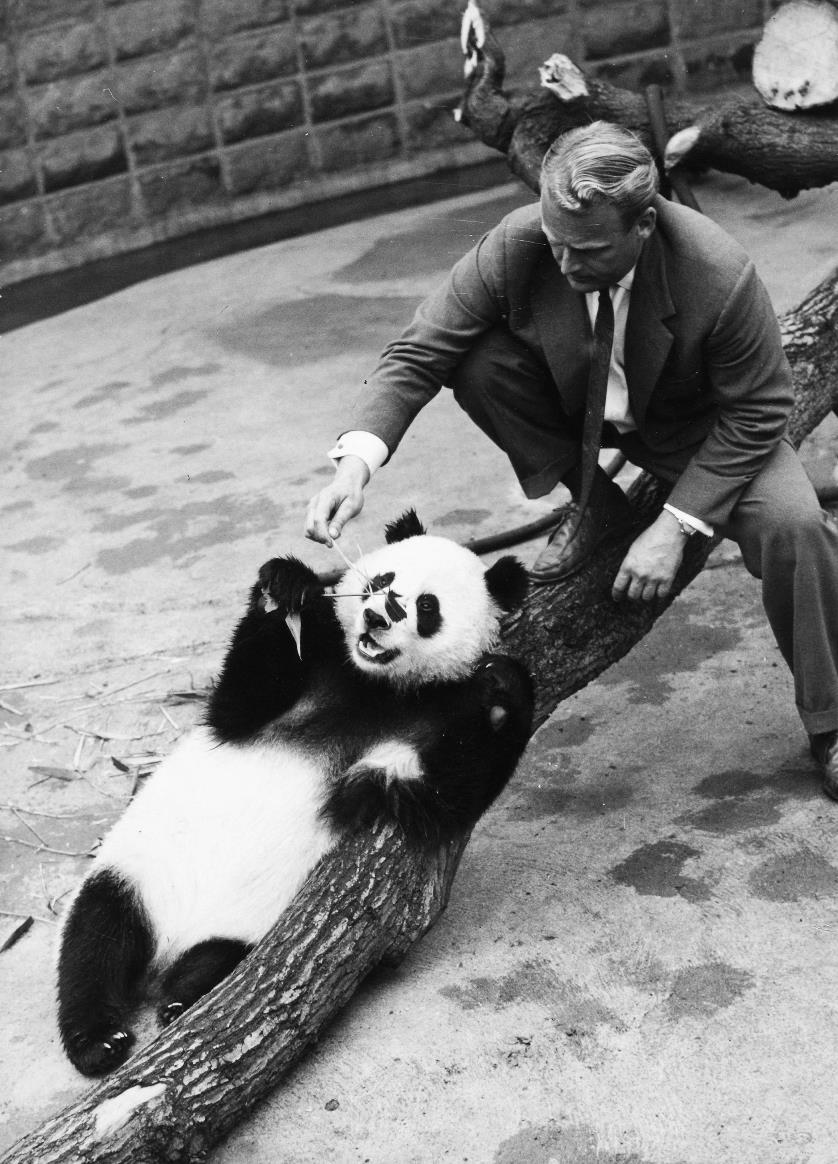

Chi-Chi, perhaps the most beloved of London Zoo’s pandas, 1958. Catalogue reference: MT 96/163

The files cover a huge range of topics and policy areas, showing the thinking inside Number 10 on a myriad of issues. Here, my colleagues, Richard and Juliette and I have picked out three stories from the files that piqued our interest.

‘Get your tanks off my lawn’

Harold Wilson once famously told a union leader, ‘Get your tanks off my lawn’; however, a transcript of a conversation between John Major and Boris Yeltsin found in one Prime Minister’s Office files released today reveals that foreign leaders occasionally had more tangible problems.

Throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev had enacted a series of reforms that had led to a de-escalation of the Cold War and the reduction of Soviet influence in Eastern Europe. Inside the Soviet Union these reforms had meant greater autonomy for the constituent republics. In 1991 Boris Yeltsin was elected to the new post of President of the Russian Republic and was widely acknowledged to be the second most important political figure in the Soviet Union.

Gorbachev’s reforms were not universally popular, and in August 1991 a group of reactionary communist leaders, referred to as the ‘Gang of Eight’ mounted a coup. They placed Gorbachev under house arrest at his dacha in the Crimea, and Yeltsin came to represent the official government.

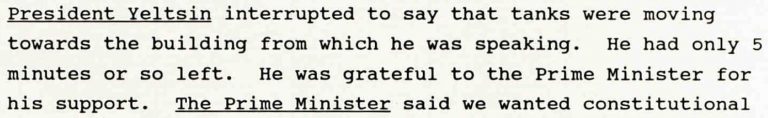

A minute of John Major’s conversations with Boris Yeltsin, in which Yeltsin informs him tanks are approaching the building he is in. Catalogue reference: PREM 19/3558/1

On the afternoon of 20 August 1991 Yeltsin was in the White House, the Russian Parliament building. The British Prime Minister, John Major, phoned Yeltsin to discuss the crisis. The Russian leader declared that ‘the anti-constitutional group were taking ever more decisive measures’ and called on the international community to ‘do all it could to free President Gorbachev [and] declare the Junta illegal’. (PREM 19/3558/1)

Major was responding to the Russian President, assuring him of the support of Britain and the European Community, when Yeltsin interrupted him. He told Major that ‘tanks were moving towards the building from which he was speaking. He had only 5 minutes or so left. He was grateful to the Prime Minister for his support.’

One can only imagine Major’s reaction to this revelation. He initially responded by reaffirming his desire that ‘constitutional law and justice prevail’, but seemingly began to realise that this was insufficient.

Major closed off the conversation with what sounds more like a line from an action movie than a salutation between world leaders: ‘He wished Mr. Yeltsin good luck and Godspeed and hoped to speak to him again very shortly.’

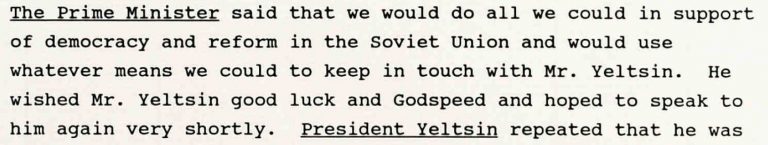

John Major wishes President Yeltsin “good luck and Godspeed” in the face of the tanks. Catalogue reference: PREM 19/3558/1

Ultimately the attempt by the Gang of Eight to storm the Russian Parliament building failed due to popular opposition. Yeltsin emerged from the crisis as a hugely enhanced figure, and the Soviet Union as an institution was fatally weakened. The coup set the scene for the final dissolution of the Soviet Union later in 1991.

This transcript of the telephone conversation is a truly remarkable document, capturing all of the immediacy and drama of the event. It highlights how extraordinarily tense this moment of very recent history was, and reinforces just how easy it would have been for circumstances to turn out very differently. From Major’s perspective, sitting in London, it must also have demonstrated that, no matter how difficult the political situation in the UK may have been, at least the tanks in Westminster were only ever metaphorical.

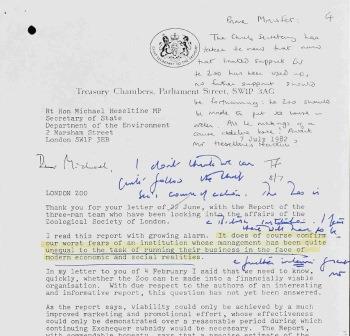

‘Pandas and politicians are not happy omens!’

‘Panda Diplomacy’ – the giving of giant pandas as gifts to other nations – has been a practice in China since the 7th century and was a feature of Cold War politics, with the United States famously receiving two pandas after President Nixon’s 1972 visit to China.

However, as revealed in the newly released file PREM 19/3783, it seems that Margaret Thatcher was sceptical of the benefits of panda diplomacy.

In 1981, London Zoo was in financial difficulties. Its President, Lord Zuckerman, got in touch with Thatcher via Cabinet Secretary Robert Armstrong, with a novel suggestion for how the Prime Minister might boost the Zoo’s profile.

The Smithsonian Institute in Washington DC was at the time interested in borrowing the Zoo’s male panda for mating purposes. Zuckerman had the idea that Thatcher might want to make this panda swap a showpiece of her forthcoming visit to the United States, to boost the Zoo’s profile and ‘benefit Anglo-American relations’. He suggested that Mrs Thatcher ‘might like to take the panda in the back of her Concorde’ when visiting the US.

Margaret Thatcher reacts to the suggestion she takes a panda with her on Concorde, 1981. Catalogue reference PREM 19/3783

However, it transpired that Mrs Thatcher was a lady not for turning up with a panda. ‘I am not taking a panda with me. Pandas and politicians are not happy omens!’ she wrote, seemingly concerned that the fickle fertility of pandas might cast a shadow on her visit.

Zuckerman was not one to quit easily though, particularly considering the dire financial straits which afflicted the Zoo throughout the 1980s and early 1990s.

In 1982 he tried once more. Again writing through Robert Armstrong, Zuckerman made it clear that the Zoo desired a fertile female panda. He hoped that, if offered one on her forthcoming visit to China, the Prime Minister would accept.

It seemed a simple enough request, and Thatcher’s secretary Robin Butler didn’t see a problem – ‘a bit passé, but no doubt you would not look a gift horse (or even a panda) in the mouth?’

However, Mrs Thatcher was reluctant, again perhaps fearing being embroiled in a panda-monium which would end up, to mix a metaphor, being an albatross around her neck. ‘Yes – I would [refuse]’, she replied to the suggestion. ‘The history of pandas as gifts is unlucky.’

Margaret Thatcher reacts to further suggestions she get involved with pandas, 1982. Catalogue reference: PREM 19/3783

There would be no panda-ring to the Zoo’s suggestions it seemed – ‘No pandas. No acknowledgement necessary,’ noted Butler as he forwarded Thatcher’s comments on, putting an end to Zuckerman’s scheme for a renewal of panda diplomacy.

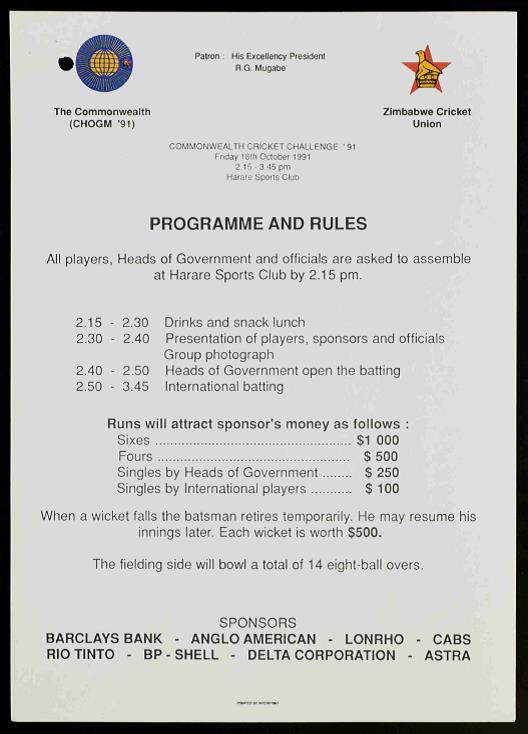

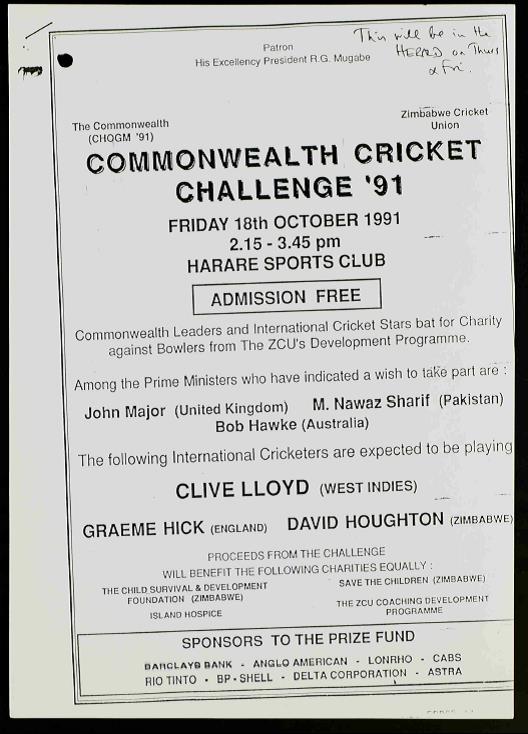

‘Cricket unites nations on all continents’

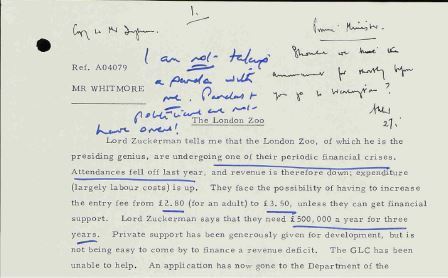

Programme and rules for the Commonwealth Cricket Challenge ’91. Catalogue reference: PREM 19/3908

The 1991 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM) was held in Harare, Zimbabwe. Recently released file PREM 19/3908 tells an interesting side-story. Ahead of the meeting on 9 September 1991, the Prime Minister of Pakistan, Nawaz Sharif, wrote to John Major suggesting a charity cricket match should be organised. ‘Cricket unites nations on all continents,’ he wrote, and as an ‘avid follower of the game’ he ‘would love to take part in such a match’.

John Major was very keen. So was Mark Williams, the Counsellor at the British High Commission in Harare, who just so happened to be the Zimbabwe correspondent for Cricketer Magazine. The British High Commissioner, Kieran Prendergast, was less taken with the idea. Writing to Stephen Wall, Major’s Private Secretary, he insisted that ‘the idea of any cricket match at Victoria Falls’ – where the Heads of Government were due to spend the final weekend – was ‘a non-starter’. ‘It is too hot,’ he said, ‘there is no ground there, and I understand the PM’s knee is anyway not up to a long innings.’ Not being ‘a member of the cricket faith’, Prendergast suggested it might be enough to gather a few ‘cricket aficionados’ for an informal supper party, and that Mark Williams’ house was the ideal venue as it was ‘well decorated with cricketana’.

Poster advertising the Commonwealth Cricket Challenge ’91. Catalogue reference: PREM 19/3908

As it often does, though, cricket prevailed. The ‘Commonwealth Cricket Challenge ’91’ was held at the Harare Sports Club on Friday 18 October 1991. Among the Heads of Government who accepted invitations to play were John Major, Nawaz Sharif (who had been ‘practising in the nets in Islamabad’) and Bob Hawke from Australia. They were joined on the ground by famous international cricketers Clive Lloyd, Graeme Hick and David Houghton.

The match raised $71,763, which went to the Child Survival and Development Foundation (Zimbabwe), Save the Children (Zimbabwe), Island Hospice, and the Zimbabwean Cricket Union’s coaching development programme. Cricket equipment was also donated, to be used in under-privileged areas in Zimbabwe.

It was, by all accounts, a very friendly event. The jacarandas were in full bloom and everyone in good spirits. John Major later said he had ‘approached the occasion with the greatest trepidation’ as he had to bat, but he needn’t have worried – it was decided before the match that if he did want to face a token ball, ‘a bowler who [could] be relied on to bowl a slowish long-hop outside off stump [would] be carefully chosen’.

CHOGM 1991 was also a success, and must have further convinced John Major that, as he put it in a letter to the President of the Zimbabwe Cricket Union on 20 October 1991, ‘after the English language and the common law, cricket is the third unifying thread of the Commonwealth’.

It is a pity that there are so many gaps in the number of files being released with others being retained, even on European policy. ‘London Zoo’ is actually the Zoological Society of London, as stated in the body of the Treasury letter above. There are a number of other interesting files (including divorce in the Royal Family). Personally the best set of releases today are the GFM 33 (German Foreign Ministry copies) are the papers about leading personalities, Rudolf Hess and other matters relating to Germany in 1939 and unofficial talks with the UK in 1938, alas the file on the Neville Chamberlain mission is ‘missing at transfer’

[…] UK: Prime Minister’s Papers From 1992 Released Online by National Archives ||| Learn More in this Blog Post ||| Access […]