100 years ago today saw a titanic struggle between the British and German fleets in the largest naval battle of the First World War. In between the smoke and the mist of the North Sea, over 50 of the most powerful dreadnought battleships and battlecruisers fought in a deadly game of cat and mouse. Neither side achieved the result they were looking for and the battle has become one of the most heavily contested aspects of the history of the First World War. New research being done between The National Archives and the National Maritime Museum is serving to return the stories of the individual service personnel to this and will provide a vital new tool for genealogists and historians interested in the battle.

On 30 May 1916 the German battlecruiser squadron under Admiral Hipper put to sea, shortly followed by the main High Seas Fleet under Admiral Scheer. Their aim was simple; to try to use the battlecruisers as bait to lure a part of the numerically superior British fleet into action with the main German force. If they could destroy part of the British fleet in detail it would help shift the balance of power at sea in Germany’s favour, something that could knock Britain out of the war. Yet unbeknownst to the Germans, the British were aware of their movements. For some time they had been intercepting and decoding German signals, and saw this as a perfect opportunity to achieve the decisive victory over the German fleet which had alluded them for the previous two years. By dusk on 30 May the two most powerful battlefleets yet assembled were steaming towards each other, both intent on action. The scene was set for the greatest naval battle of the First World War.

The two forces met in the afternoon of 31 May, when scouts for Admiral Beatty’s British Battlecruiser Squadron sighted smoke on the horizon. Further investigation revealed it to be the five battlecruisers of Hipper’s opposing force. (ADM 137/1642) A year earlier they had met in the Battle of Dogger Bank and Beatty had failed to destroy his numerically inferior rival. This time he was desperate to finish the job. The Germans immediately began retreating to the south with Beatty in hot pursuit. The two forces opened fire at a range of 18,500 yards, but the German gunnery proved to be ‘very rapid and effective’. (ADM 137/301) In a relatively short space of time the British ships Indefatigable and Queen Mary were both struck by shells that penetrated their armour and caused explosions in their magazines, sinking both ships with the loss of almost their entire crews. Beatty’s flagship Lion was also badly damaged and only survived when a magazine was flooded to prevent a catastrophic explosion.

HMS Indefatigable (Cat ref: ADM 176-360)

As the battle continued, British firing improved and the four new battleships of the 5th Battle Squadron – which was attached to Beatty’s battlecruisers – came into range. This increased firepower was just beginning to tell when the Germans sprung their trap. Throughout the battle so far the ships had been steaming south at high speed, directly into the path of the main German battlefleet. Due to a breakdown in communications the British admirals were unaware that the High Seas Fleet was in the area, and so they were taken by surprise when the ships loomed out of the mist. Beatty was now hopelessly outgunned and desperately reversed course, heading north. The Germans followed whilst continuing to pound the rearmost ships in Beatty’s line.

HMS Chester (Cat ref: ADM 176/902)

Just as Hipper had drawn Beatty’s battlecruisers south into the path of Scheer’s main fleet, now it was the turn of the British ships to act as bait, pulling the Germans north onto the guns of the overwhelmingly superior British Grand Fleet. The 5th Battle Squadron – closest to the German fleet – took heavy fire, but in the process meted out ‘very severe punishment’ on the German battle cruisers. (ADM 137/301) The Germans were totally unaware of the existence of the Grand Fleet to the north, and for a time it looked like the British would get exactly the battle they desired. Unfortunately Beatty’s communications with the Grand Fleet commander Admiral John Jellicoe left a lot to be desired. When combined with the difficulties of precise navigation in the misty waters of the North Sea this meant that Jellicoe did not know how to deploy his forces. In the confusion, a number of brief and brutal encounters took place as cruiser forces from both sides blundered into the enemy’s main battlefleets. In one instance, the British battlecruiser Invincible was hit by a number of heavy calibre shells and blew up.

The sudden appearance of the entire British Grand Fleet took the Germans completely by surprise. Jellicoe had successfully managed to deploy his fleet “crossing the T” of the Germans, which meant that he could bring most of his heavy guns to bear whilst only a few Germans could respond. The resulting action saw the British inflict heavy damage on the lead ships of the High Seas Fleet. Scheer was in a dire position steaming directly towards an overwhelmingly superior enemy. As such he order the entire German fleet to turn 180 degrees simultaneously. This was an extremely high risk manoeuvre which could easily have resulted in collisions and a complete breakdown of the German line. The German ships pulled off the manoeuvre and proceeded south away from the oncoming British.

There followed a series of confused manoeuvres and engagements where Scheer desperately sought to avoid a pitched battle with Jellicoe, and was waiting for nightfall to attempt to slip passed the British and back to the safety of the German coast. At one point Scheer was forced to order his remaining battlecruisers to steam directly for the Grand Fleet in order to give his battleships time to escape. The German ships were pounded by shells from almost the entire Grand Fleet, but remarkably none were sunk. This came to be known as the Death Ride.

As night fell Jellicoe ‘rejected at once the idea of a night action’ as ‘always being very largely a matter of pure chance’. (ADM 137/301) Instead, he gambled on ambushing the Germans at dawn as they returned to their bases. He incorrectly guessed which route the Germans would take and Scheer slipped passed him and home safely.

As soon as the fleets arrived home the arguments started over who ‘won’ the Battle of Jutland, and why each side failed to achieve what they set out to. Within the Royal Navy, attention quickly focused on why the vastly more powerful British force had not landed a knockout blow. The recriminations around this would continue to divide the navy for decades and still dominates discussion of the battle.

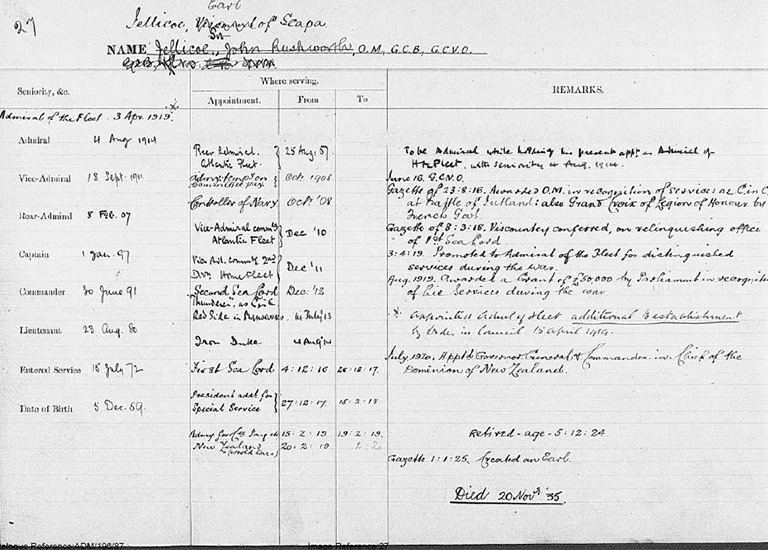

Officers’ service record for Admiral Jellicoe (Cat ref: ADM 196-87-27)

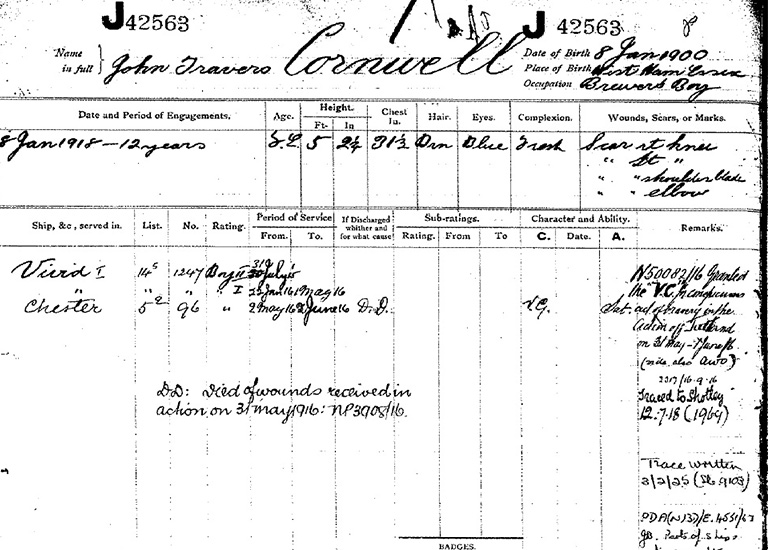

The memory of the battle lives on in the holdings of The National Archives and is available in a variety of forms, including the stories of individual men recorded in the rating’s service records, in ADM 188, or the officer’s service records available in ADM 196. These record series cover the dates of First World War service and, for the dates 1914-1918, both series are catalogued by name and downloadable from our website for a fee. Additionally, the official history of the Royal Navy during the First World War was written using files and correspondence that can be found in the ADM 137 record series. As a result of our world class holdings, The National Archives, The National Maritime Museum (NMM) and the Crew List Index Project team (CLIP) are building on their successful collaboration that resulted in the Merchant 1915 Crew List Index project, and (with the help of a team of e-volunteers from all over the world) will be creating a free-to-search database resource relating to all the Royal Navy officers and ratings that served in the First World War, entitled Royal Navy First World War Lives at Sea. This resource, which will be hosted by the National Maritime Museum, is scheduled to launch in mid June 2016 with the aim of completion by November 2018. It will be based principally on the Royal Navy service records held by The National Archives.

Seamen’s Services record for Jack Cornwell, who received a posthumous Victoria Cross for his gallantry at Jutland (Cat ref: ADM 188-732-42563)

This project will create the most significant online data resource for the study of the Royal Navy during the First World War, by creating a unique resource that marks and commemorates the Royal Navy’s contribution to the war effort through the lives of those officers and ratings who served. Our hope is that it will allow and promote a wide and diverse variety of research into the composition and operations of the Royal Navy during the War. This could be specifically in relation to individual officers and ratings through their personal and service histories, to wider thematic and historical studies – as the database will indicate where men were recruited from, their previous trades and it will enable users to identify crew lists for specific ships and submarines for given dates. Such lists do not survive for the First World War and so – for the very first time – researchers will be able to place officers and ratings in naval battles of the War and study topics from mortality rates to invalidity and its causes. Of great interest then, especially on the 100th anniversary of the biggest naval battle of the First World War, is that the database will indicate which battles a rating or officer served in; Heligoland Bight, Coronel, Falkland Islands 1914; Dogger Bank 1915 and, of course, the Battle of Jutland 1916. The resource will allow researchers the opportunity to create comprehensive data relating to every member of the Royal Navy who saw action on this historic day 100 years ago.

Please note, that as a starting point, the resource will be focusing on Royal Navy personnel and not Royal Naval Reserve or Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve ratings and officers.

If you are interested in the history of the Royal Navy and its personnel, or are looking for some hands on experience working with original documents and would like to help us transcribe these service records, please get in contact at crewlists@nationalarchives.gov.uk.

I have my granddads naval records on velum and some photos and a diary if a copy would be of use to you.he was on hms new Zealand and served in the battle of jutland any many others

Of course ‘recieve’ is spelt ‘receive’. I am surprised you didn’t mention the flag signals as shown by the BBC programme this week which established that flags couldn’t be viewed several miles away, in other words using the methods used during Nelson’s time at the Battle of Trafalgar were outdated and so, it seems, were the Admiralty’s tactics.

Commemorating the Battle of Jutland, a display of documents, on the day of the centenary, was very good indeed. I am particularly grateful to Dr Richard Dunley for so willingly answering my many questions.

My great uncle was yeoman of signals to Admiral Beaty on board HMS Lion at the Battle of Jutland. Is it possible for anyone to help me find out details of his service.

Thank you

Hi Michael,

Unfortunately we’re unable to help with family history requests on the blog, but if you go to our contact us page: http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact/ you’ll see how to get in touch with our record experts via phone, email or live chat.

I hope that helps.

Nell