The disaster of the Great Fire of London was keenly felt by those who had lost everything to the blaze in early September 1666. Among them were the women who worked the capital’s streets distributing the only newspaper of the time, ‘The London Gazette’. In letters preserved at The National Archives one of these women, Mrs Andrews, pointed out that she had lost all her worldly goods and had ‘noe more cloathes than shee had on her back’.[ref]SP 29/174 f.175. Hickes to Williamson (12 October 1666).[/ref]

Gazette Seller, © Trustees of the British Museum

Mrs Andrews was requesting better pay and conditions from a government which had just taken direct control over newspaper publishing and was struggling to secure its distribution. Her argument is contained in letters written from her contact at the Post Office, James Hickes, to the undersecretary of the Secretary of State.

Similar records of the contact between these women and government exist in a number of other letters. Paraphrased and stripped down by Hickes, he nevertheless gave their voices space to express themselves. These letters offer an intriguing glimpse into the manner with which women were able to use their voices and labour at this time to argue for better conditions. These were not the modest housekeepers who characterised the conduct manuals of the period, but working women with a strong sense of their rights and ability to negotiate.

Writing in mid-November 1666, a month after the Fire, Mrs Andrews was in a desperate situation. Cold weather was setting in and her job entailed spending much of the day outside. Unlike women born into means or a stable trade, book-women (as they were called) could be said to be at the margins of a society to which they were integral.

Since the emergence of regular newsprint several decades previously, women had been employed to distribute this wildly popular medium as street-sellers and hawkers: they adopted news into the wider store of pamphlets and ephemera that they sold across London and the country as a whole. A book-woman could supply you with news, and also with entertainment and decoration in the form of printed ballads to be sung or pasted onto walls. For those with more daring tastes, book-women also often distributed underground publications.

Even as the secretaries negotiated with Mrs Andrews, they were interrogating other book-women, like Elizabeth Bud, about the ‘Catholique Apology’, a pamphlet arguing for fairer treatment for Catholics.[ref]SP 29/180 f.145. (5 December 1666).[/ref] The diarist Samuel Pepys described it as ‘much called after’, stole a glimpse of the pamphlet from his bookseller Mrs Michell, and decided that it was ‘very well writ indeed’. In supplying the demands of a public hooked on news-reading, entertainment, and sedition – all of which might overlap – these book-women worked in an essential field.

Even those employed to distribute the state newspaper were not free from intrigue. Indeed, they were able to use it to their advantage. ‘The Gazette’ faced competition from an alternative newspaper, the ‘Current Intelligencer’, run from a rival governmental department. The book-women were drawn into this contest of warring newsmongers. The Current Intelligencer was proving particularly liberal to them in an attempt to monopolise their valuable distribution network: Hickes warned, they ‘now give very kind & all to promote their intelligence’ with the women.[ref]SP 29/166 f.192. Hickes to Williamson (8 August 1666).[/ref]

The book-women were also able to use precedents established by the previous newspapers, run by the aristocrat Sir Roger L’Estrange, to argue for better pay and perks. These newspapers had been taken under state control the previous year. Before the Fire, they communicated to the secretariat that ‘They hope you will be as good a master to them as Mr LeStrange was’.[ref]Ibid.[/ref] Afterwards Mrs Andrews made the same point, asking that their new state employers should ‘remember her presently as formerly Mr LStrange did’, and provide regular bonuses.[ref]SP 29/174 f.175. Hickes to Williamson (12 October 1666).[/ref]

Meanwhile, Mrs Andrews was able to use a side-employment. She spied on the newspaper’s printer to ensure a personal meeting with the undersecretary, although she was hurried into his house secretly and out of the sight of the servants.

Records of grants and the women’s thanks indicate that they were successful in manipulating precedent and competition to ensure proper pay and patronage.

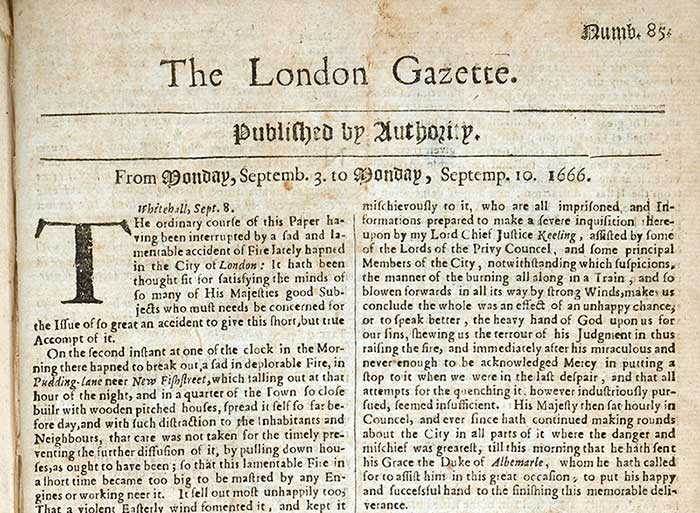

The book-women were not just concerned with pay, but also with conditions. This was an issue thrown into sharp relief in the aftermath of the Great Fire of London, when much of the city had been obliterated by the blaze. Although burnt out of its printing house, the Gazette itself had only missed one edition and was back within a week, packed with reports on the Fire.

ZJ 1/1 (1) London Gazette 3 September 1666

It seemed to be business as usual, but there were tensions behind the scenes. The printer whom Mrs Andrews was spying on, Thomas Newcombe, seems to have been badly affected by the Fire. The book-women informed the secretariat that he ‘careys himselfe more strangly then others’ and had set up ‘in the Churchyard’.[ref]SP 29/178 f.13. Hickes to Williamson (12 November 1666).[/ref] This was possibly the gutted ruins of St Pauls Churchyard, for the women complained that they would ‘hazard their halths if not their Liues by attending him’, given that the ‘stench of ye earthe is much offensiue & unholsome’.[ref]Ibid.[/ref]

Newcombe, who was a well-respected and prolific printer, cut a strange figure in the aftermath of the fire – visibly traumatised yet still pumping out newspapers among the rubble of a church and a scorched graveyard. Small wonder the book-women were reluctant to stop by, particularly as doing so entailed long walks during a cold November ‘through all weather and ways at such a distance’.[ref]Ibid.[/ref] Remember also Mrs Andrews’ complaint that she had ‘noe more cloathes than shee had on her back’.[ref]SP 29/174 f.175. Hickes to Williamson (12 October 1666).[/ref] By citing the dangers to their wellbeing, the women asserted their own agency and right to determine the terms of their employment, threatening to ‘leave him [Newcombe] to dispose of his bookes as he cann’ if their conditions were not improved. Some walked away from the job in disdain.[ref]SP 29/178 f.13. Hickes to Williamson (12 November 1666).[/ref]

The book-women’s contact, James Hickes, wrote insistently in their favour. After the Fire, he told his boss that Mrs Andrews ‘promises all diligence’ for ‘she is one of ye greatest payne stakers’.[ref]SP 29/174 f.175. Hickes to Williamson (12 October 1666).[/ref] Later letters indicate that her demands were met: evidently the other book-women were also willing to argue their corner.

We often imagine the past as a time when concerns about workplace conditions would be low on a list of priorities, and where women, particularly those at the margins of society, would have little agency to engage with the state and their employers.

These letters show the existence of an alternative world, where employees could negotiate with the state through a use of precedent and competition to ensure proper recognition. Such questions were often ones of survival after a disaster like the Fire, and the book-women used the importance of their often overlooked role in disseminating news to their advantage.

Thank you for this interesting post. Do you have references for this documents? Many thanks.

Hi Matt. Apologies for not including them sooner, but I just wanted to let you know that we’ve now added the relevant footnotes for the post.

Thanks!