Due to its longevity and impact at home and abroad, Henry VIII’s break with Rome stands out as one of the most notable events in British history.

For a long time, Henry was determined to have a son and heir to his throne and secure the Tudor dynasty. His wife, Catherine of Aragon, had produced no surviving male heirs and Henry feared that his daughter, Mary, would be challenged if she tried to rule. Henry was willing to go to extreme measures to acquire a legitimate male heir and, after becoming enamoured with Anne Boleyn by 1527, he had the final incentive to initiate the annulment proceedings. These proceedings were built on the notion that Henry’s marriage to Catherine was ‘invalid’ as her previous marriage to Henry’s brother, Arthur (1486-1502), had been consummated.

Only the Pope had the authority to authorise an annulment, and Henry’s attempts to gain this approval proved difficult. While it is unlikely that Henry intended to break with Rome as a result of these proceedings, it is evident that he was prepared to defy the Pope in his efforts to secure a male heir.

The National Archives holds a vast number of records relating to the English Reformation; for this blog I have chosen a selection of documents from series SC7, E30, and SP1 which highlight the deteriorating relations between Henry VIII and Pope Clement VII in the years leading up to the break with Rome.

Defender of the Faith

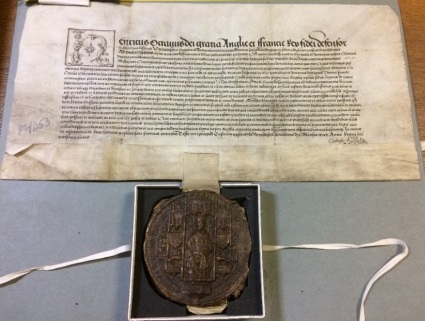

Following Henry VIII’s ascension to the throne in 1509, he had a fairly good relationship with the papacy. In fact, on 11 October 1521, Henry was made Fidei Defensor (Defender of the Faith) by Pope Leo X, following his condemnation of Martin Luther in his book entitled ‘Defence of the Seven Sacraments’. His title of Defender of the Faith was reconfirmed in a papal bull by Pope Clement VII on 5 March 1524 (SC7/14/3). This was only ten years before the break with Rome, which leads one to question how such a dramatic shift in relations could have occurred so quickly.

One side of the Papal seal depicting Saint Peter and Paul with the inscription “Gloriosi Principes terrae SA PA SA PE” which translates as “Glorious leaders of the earth, Saint Paul and Saint Peter” (Catalogue reference: SC7/14/3)

This Papal Bull confirming Henry’s title as Defender of the Faith included the gold seal of Pope Clement VII, attached to a red and yellow silk cord, indicating the high importance of the document. Papal seals were usually made from lead and were attached with a hemp cord if they were deemed less important.

Permission from the Pope to check validity of marriage

On 30 May 1529, Henry gave licence under the great seal to the two papal legates a latere – Cardinal Lorenzo Campeggio and Cardinal Thomas Wolsey – authorising them to investigate the ‘validity or invalidity’ of his marriage to Catherine, according to the commission from Pope Clement VII made on 8 June 1528. At this stage, the Pope was complying with the king’s wishes.

This document includes Henry VIII’s famous Great Seal which authenticated the document. The seal depicts Henry on his throne with his orb and sceptre, highlighting that he was the rightful king of England.

Henry VIII’s licence to Cardinal Wolsey and Campeggio to begin the annulment proceedings (Catalogue reference: E30/1453)

Delays to the marriage dispute

Clement delayed the marriage dispute on several occasions: for example, on 29 August 1529 he suspended the proceedings until the following Christmas. 1 These delays were influenced by the Pope’s conflicts with the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, who – unfortunately for Henry – was also the nephew of Catherine of Aragon.

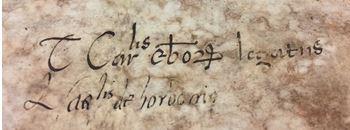

On 6 May 1527, Charles V sacked Rome, forcing the Pope to flee to Castel Sant’Angelo, where he was effectively Charles’ prisoner for six to seven months. On 16 September 1527, the Cardinals of Bourbon, Salviati, Lorraine, and Sens, along with Cardinal Wolsey, wrote to Clement VII expressing their concern at his imprisonment, and their intention to hold invalid any acts extorted from the Pope while in captivity. Wolsey was aware that the Pope could not be trusted while he was under the watchful eye of the Emperor, and feared any judgement the Pope might make regarding Henry’s marriage. To make matters worse, on 29 June 1529 Clement VII was forced to make peace with Charles V, making the Pope an official ally of the Emperor. 2

On 13 July 1530, several English temporal lords wrote to Clement begging him to consent to the king’s desires regarding the annulment, as it was becoming such a burdensome issue. This document highlights not only the Pope’s continued delays to these proceedings, but also the growing concern and anxiety within the English Church regarding the status of Anglo-Papal relations. 3

It is likely that these delays were also angering the impatient king.

Signatures of Cardinal Thomas Wolsey and Cardinal Louis de Bourbon authorising their letter to the Pope in captivity (Catalogue reference: E30/1449)

Papal resistance to Excommunicating Henry

On 25 January 1533, Henry formally married Anne Boleyn without having gained an annulment of his marriage to Catherine. In May of the same year, the new Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer, declared Henry’s marriage to Catherine ‘null and void’. Outraged, Charles V ordered Clement to make a judgement on Henry’s marriage to Anne Boleyn, but Clement delayed his judgement. 4

The Pope and the Emperor finally agreed on the sentence of excommunication against Henry, which Clement suspended until September 1533. 5

There’s a clear sense from the records that Clement VII was resistant to the idea of excommunication. In fact, Clement’s final sentence of excommunication against Henry never materialised and it was his successor, Paul III, who had to excommunicate the English king on 17 December 1538, after the king had ignored yet further threats from the papacy on 18 November. 6

An evening with Suzannah Lipscomb, Friday 3 November

This brief study of some of the Reformation records at The National Archives has started to demonstrate the complexities of Anglo-papal relations in the lead up to the break with Rome, which were influenced by many factors including imperial pressure, papal inaction, and Henry’s impatience.

Some of these themes will be explored in a forthcoming talk by historian, broadcaster and award-winning academic Dr Suzannah Lipscomb, at a special evening event at The National Archives on Friday 3 November.

Notes:

- 1. E30/1486. In the British Library, there exists a draft in Gregor Casale’s hand (Casale was a royal diplomat representing Henry VIII at the Papal court) concerning a promise Clement VII had made to Henry that ‘three months after the advocation of the king’s cause, he will pronounce a sentence of divorce, and give the king licence by bull to contract a second marriage’, Cotton MS. Vitellius. B. XI. 247; Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, V.4, 1524-1530, (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1875), 2629. ↩

- 2. Note on the Treaty between Clement and Charles dated 23 December 1529, recorded in the Venetian state papers, PRO 30/25/14. ↩

- 3. E30/1012A. ↩

- 4. On 13 June 1533, Bonner informed Henry VIII that Charles was pressuring Clement to make a judgement against Henry, SP1/77 f.2; On the same day, Bennet confirmed to Henry that Charles was encouraging the judgement and excommunication which the Pope had been delaying, SP1/76 f.63. ↩

- 5. SP1/77 f.193 ↩

- 6. 18 November 1538, SP1/238 f.159. ↩

[…] Due to its longevity and impact at home and abroad, Henry VIII’s break with Rome stands out as one of the most notable events in British history. For a long… Go to Source […]

Do you hold any records regarding Charles Reynolds? It would be interesting to know if there were contacts with English dissidents. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Reynolds_(cleric)

Hi Noel,

Thanks for your comment.

We can’t answer research requests on the blog, but if you go to our ‘contact us’ page at http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact/ you’ll see how to get in touch with our record experts via phone, email or live chat.

Best regards,

Liz.

On reading this, it becomes clear that in attempting to keep peace between Henry VIII, Charles V, and the Church, Pope Clement VII held out hope for a compromise — for years.

Regarding this situation it’s difficult to feel anything but sympathy for Clement VII. It’s certainly a difficult spot to be in.