In Afghanistan, just like elsewhere in the world, the British and the French squabbled over archaeology.

In 1921, British archaeologist Sir Aurel Stein, wanted to excavate in Afghanistan. He wasn’t pleased to see his request denied while his French colleague, Alfred Foucher, seemed to be given everything he asked for. When the British Minister in Kabul, Humphrys, approached the Afghan government, he was told it was for security reasons. However, he reported, it seemed ‘possible that objection was really due to Amir being pledged, under an agreement with the French government, to offer Foucher exclusive rights to explore Graeco-Buddhist remains in Afghanistan’ (FO 371/8082).

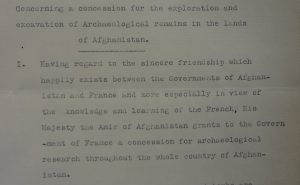

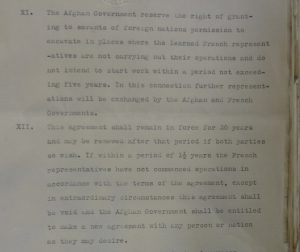

The India Office found it difficult to understand that ‘the Afghans [could] convince themselves that it [would] really pay to give preference to a French archaeologist over a British’. However difficult it was to believe, the French did sign a convention with Afghanistan. Article 1 gave the French exclusive rights to conduct archaeological research throughout the country; article 11 seemed to mollify this a bit, stipulating that other foreign missions could work in Afghanistan provided the French approved it; and article 12 explained the convention would be valid for 30 years provided work wasn’t interrupted for more than 18 months (FO 371/8082).

- French-Afghan Convention, article 1, 1922 (catalogue reference: FO 371/8082)

- French-Afghan Convention, articles 11 and 12, 1922 (catalogue reference: FO 371/8082)

In Britain, the monopoly was considered as ‘something like an affront’. Arthur Hirtzel, at the India Office, was particularly angry. He raged:

‘The present French policy of stealing marches on us in the East is beginning to lack dignity when it extends to the realm of archaeology (…), even M. Foucher must be a bit ashamed of himself’ (FO 371/8082).

He added: ‘the standard of gentlemanly conduct on the part of the French remains (…) on the same level as that of the political methods of the Afghans’. For once, the Foreign Office and the India Office stopped squabbling and joined forces in a desperate attempt to block the convention. They failed.

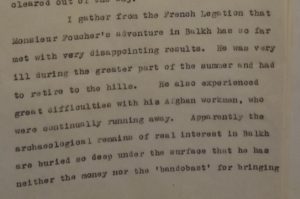

When, in 1923, French senators debated the possibility to establish a legation in Afghanistan, they mentioned the archaeological monopoly as a good reason to have a permanent presence in Kabul. The British government was very alarmed and protested. The French immediately reassured them: they had no intention of establishing a real monopoly, and Foucher actually wanted to ‘ask his eminent friend Sir Aurel Stein to collaborate with him on excavations in Afghanistan’ (FO 371/9292). This Entente Cordiale didn’t last long. Stein never got permission to work in Afghanistan, and when, in 1924, German archaeologist Ernst Herzfeld renounced to work in the country, Humphrys was quick to blame it on the French who, he reported, ‘viewed the arrival of Dr Herzfeld with the greatest jealousy and suspicion’ (FO 371/10410).

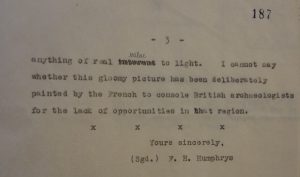

- Humphrys to Sir John Marshall (Director General of Archaeology in India), 28 November 1924 (catalogue reference: FO 371/10410)

- Humphrys to Sir John Marshall (Director General of Archaeology in India), 28 November 1924 (catalogue reference: FO 371/10410)

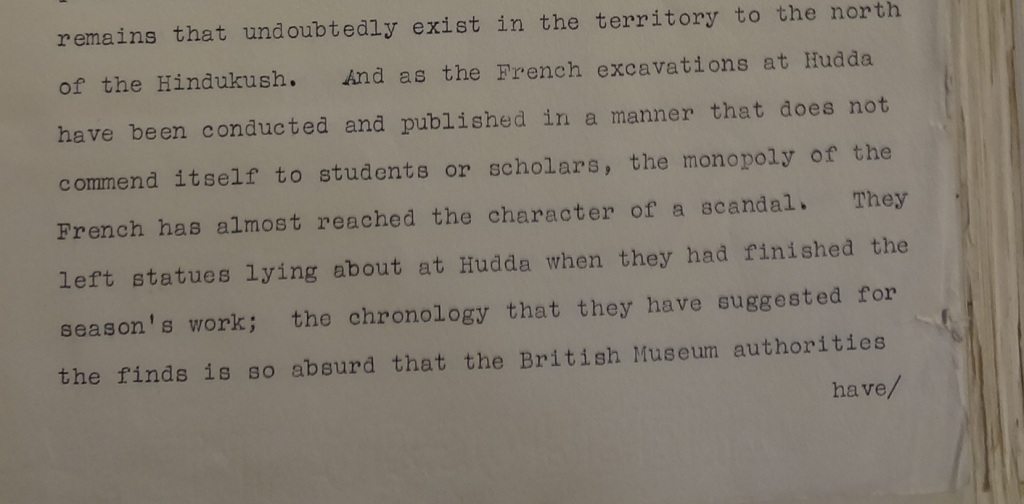

Archaeological issues resurfaced in 1938 when Evert Barger, a lecturer at the University of Bristol, enquired about the possibility to conduct an archaeological survey in the North of Afghanistan. He very clearly and very openly despised the French and their work. Writing to Crombie at the India Office, he explained:

‘as the French excavations at Hudda have been concluded in a manner that does not commend itself to students or scholars, the monopoly of the French has almost reached the character of a scandal’ (FO 371/22254).

His proposal, in any case, wouldn’t breach the monopoly as he wouldn’t conduct systematic excavation but only ‘archaeological reconnaissance’, in ‘discreet and unobtrusive fashion’. In April 1938, Barger met with Joseph Hackin, the head of the French Mission in Afghanistan. The meeting, Barger said, was very friendly, and Hackin ‘said he was only too glad to have the co-operation of British archaeologists’ (FO 371/22254). In Kabul, Fraser-Tytler, the British Minister, wasn’t very optimistic. He thought that the Afghans would never let a British Mission in, even with the support of the French.

In June, Barger and Hackin met with an official at the French Ministry for Foreign Affairs. Barger described the meeting as ‘most cordial’ and reported a telegram was sent to Kabul, requesting the French Minister ‘to do everything in [his] power, in conjunction with the British Minister, to secure from the Afghan Government the necessary facilities for Mr Barger and his party’ (FO 371/22254). In June, the Afghan Government notified the British Minister that permission had ben denied for security reasons. Halford, of the Northern Department of the Foreign Office commented: ‘this must be a blow to Mr Barger, but at least we shall not have to hunt for his corpse now’ (FO 371/22254).

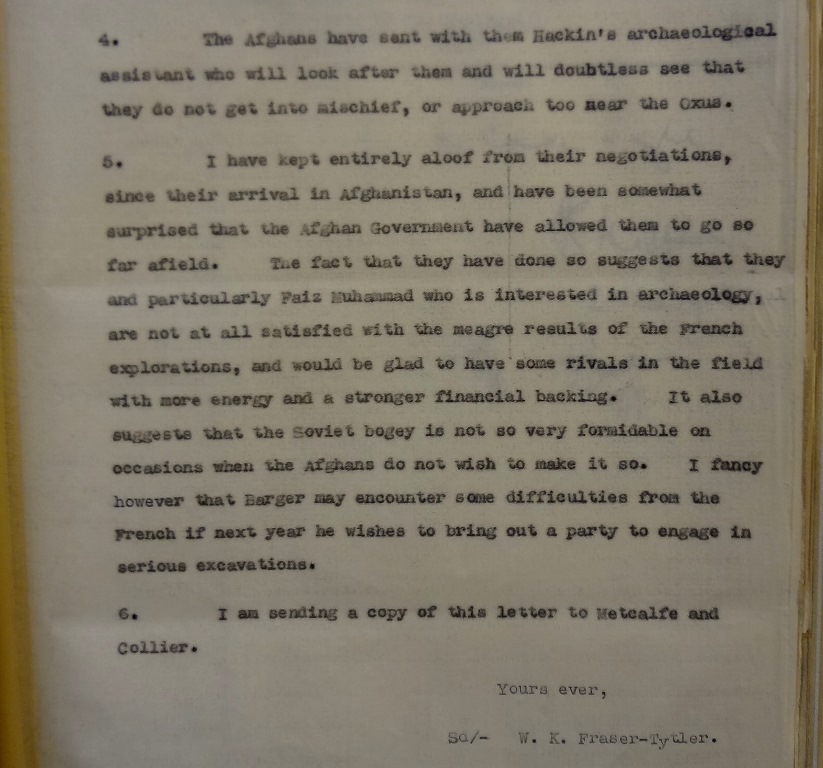

Fraser-Tytler suggested that Barger could come to Kabul, if he wanted, but would probably not be allowed to travel within the country. In July, the Afghan government refused to grant visas to Barger’s party. In August, the political situation having calmed down in Afghanistan, Barger asked if he could go to Kabul. Rather surprisingly, the Afghans agreed that he could come with an assistant and visit not only Kabul, but also Bamian and Begram, in the north. Fraser-Tytler put it down to the ‘meagre results of the French explorations’ and thought the government ‘would be glad to have some rivals in the field with more energy and a stronger financial backing’ (FO 371/22254).

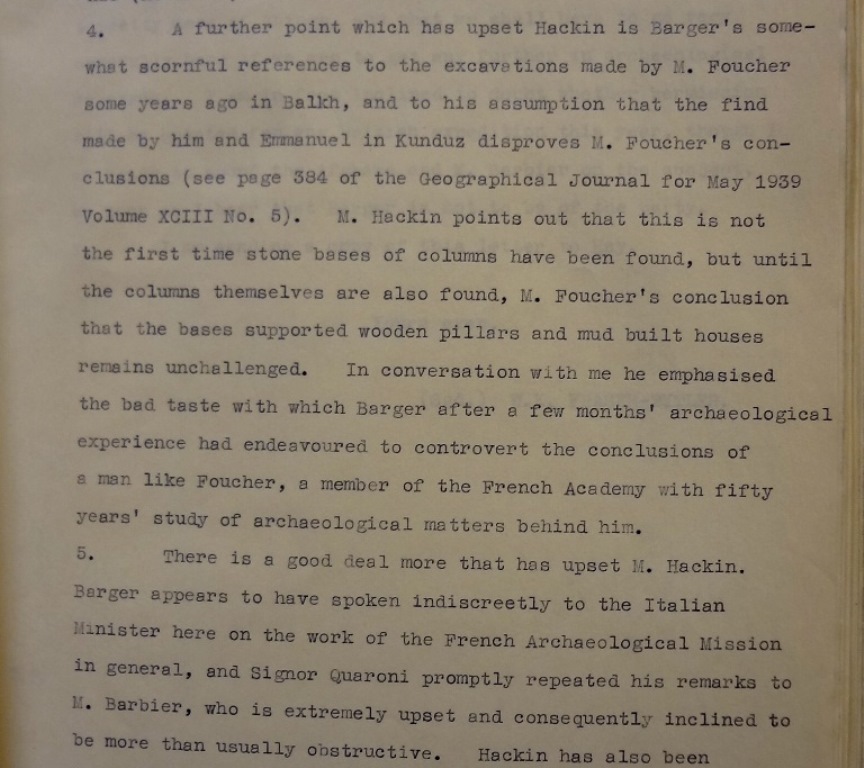

In 1939, Barger tried to mount another expedition. The new Afghan Foreign Minister seemed well-disposed, and the plan was to have a joint expedition with the French with Kenneth de Burgh Codrington, of the India Museum, at the head of the British party. The Entente Cordiale was, once more, shattered when it transpired that Barger had behaved so badly during his 1938 visit that the Afghans refused to let him come. He had discarded the advice of the Afghan official who had accompanied him and made ‘somewhat scornful references to the excavations made by M. Foucher some years ago’ in the course of a conversation with the Italian Minister. The Italian had repeated everything to the French Minister who was ‘very upset and consequently inclined to be more than usually obstructive’. Fraser-Tytler concluded that Barger had made ‘a pretty mess of things’. Unsurprisingly, Barger disputed the veracity of the accusations, and blamed it on ‘French jealousy of his work’ (FO 371/23623).

When the Second World War broke out, Hackin refused to stay in Kabul to represent the Vichy Government and joined General de Gaulle and the Free French in Britain. In June 41, he was replaced by Roman Ghirshman, described by the British Minister in Tehran as ‘a strong supporter of the Free French Movement’. From then, and until the end of the war, the British government would, rather ironically, have to defend the French concession and do everything they could for it not to lapse and pass on to the enemy. For once, the French were fighting themselves, not the British (FO 371/27041).

Ivor Pink, at the Foreign Office, wasn’t pleased to have to deal with the French and their internal squabbles, and to have to act as a post office. He commented:

‘I shall be devoutly thankful when all these Frenchmen, Fighting or otherwise, are out of Afghanistan. Their intrigues waste a great deal of time and paper and cost us a good deal in telegrams, some at least of which could be saved if Sir F. Wylie [the British Minister] would condense his comments a little’ (FO 371/34912).

Despite Pink’s despair, it was all going quite well until, at the beginning of 1943, the French Minister, René Cassin, was instructed by Vichy to dismiss Ghirshman. At the same time, Cassin, who had been working closely with the British, declared he wanted to join the Fighting French. De Gaulle and the French National Committee, anxious to preserve France’s cultural prestige in Afghanistan, wanted Ghirshman to stay put, which, they thought, would be feasible if Cassin didn’t say anything to the Afghans. They said they were prepared to finance Girshman’s work if he let them know how much he needed to conduct work ‘on a scale which, though strictly limited, [would] suffice to maintain [French] rights and allow for useful scientific work’.

- Messages from Carlton Gardens to Girshman and Cassin, 21 January 1943 (catalogue reference: FO 371/34912)

- Messages from Carlton Gardens to Girshman and Cassin, 21 January 1943 (catalogue reference: FO 371/34912)

By that time however, Ghirshman and Cassin were no longer on speaking terms. Wylie decided not to pass on the messages because of the ‘bitter personal animosity’ between the two men. In the end, Cassin left in May 1943 and Ghirshman stayed on until September.

In 1944, Barger, decidedly persistent, proposed yet another expedition with Codrington at his head. The Foreign Office agreed that Frances’s ‘monopoly rights’ were ‘really anachronistic’, but noted that it was perhaps not quite the moment to challenge the French. They added:

‘If we do want to get in on archaeology in Afghanistan, for heavens sake let us wait until some less calamitous representatives than Messrs Codrington and Barger come along. (the latter, whom I met in Persia, is most aptly named(…)). Mr Pink, who knows both C. and B., reckons that the pair of them would be worth a division of Germans in Afghanistan’ (FO 371/39961).

Squire, the British Minister in Kabul, added that he would ‘on no account have Barger in the country in any capacity’. So that was it – Britain had grudgingly protected France’s monopoly.

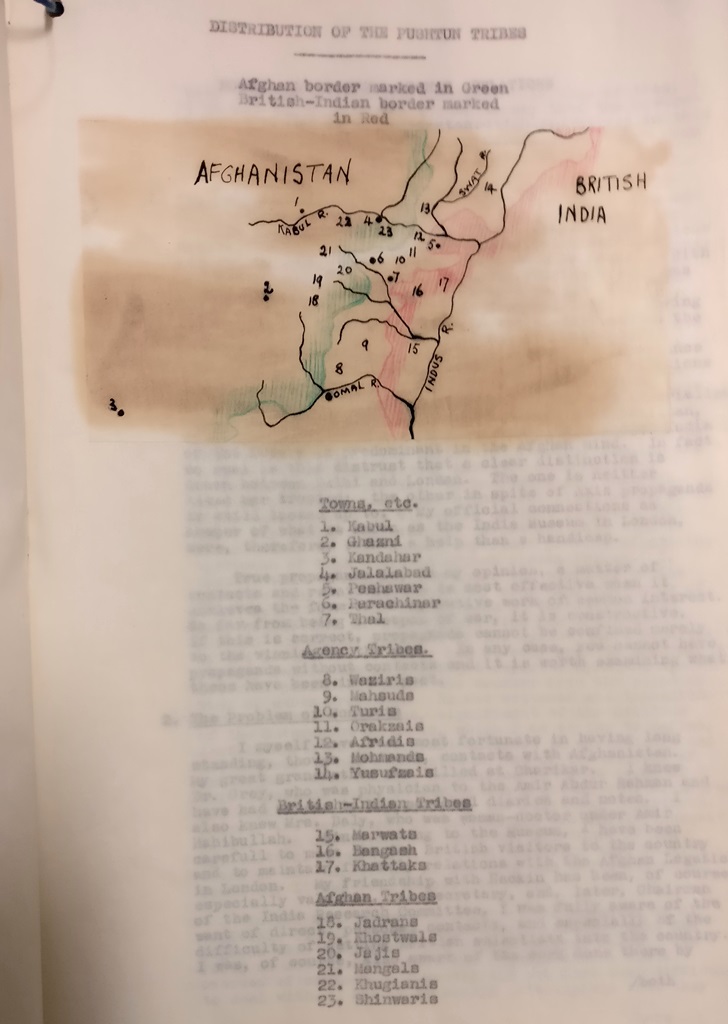

In 1951, Codrington tried, again, to mount an expedition to Afghanistan and quoted the poor state of the French Mission as a good reason to do so. At first, the British government and the Head of the French Mission, Schlumberger, were very supportive. Unfortunately, Codrington had somewhat extreme political views when it came to Afghan tribes, and a ‘strong pro-Pathanistan and pro-Indian (and anti –Pakistan) attitude’. In September 1951, the British Minister, John Gardener, reported that Codrington was suspected of espionage by the Afghan government and that Schlumberger concurred. They weren’t that off the mark – in 1940, during a quick visit to Afghanistan, Codrington had passed on an awful lot of material to the intelligence department of the Indian Government, and written a lengthy report on the country.

Even so, Gardener also thought the French ‘may also fear that Codrington is such an individualist that it may prove difficult for the two archaeological missions to be on good terms’ (FO 371/92125). The Anglo-French feud was back in full swing.

Very grateful for this blog/article. Prof K de B Codrington was my great uncle. I knew him quite well and I have some of his papers. He was great admirer of Joseph Hackin and respected his knowledge of early Buddhist archaeology and always said that Hackin had an intimate knowledge of Afghan politics. K de B was present at the excavations at Kapisa/ Begram in April/May 1940 and then stayed on in Afghanistan for at least a year till 1941. K de B also wrote an obituary for Hackin which was read out in French on Radio Kabul after Joseph Hackin his wife Ria and Robert Byron were torpedoed on board SS Jonathan Holt. K de B tried to get Hackin’s artefacts from Begram exhibited at the Warburg Institute but de Gaulle refused.. “Not till there is a Free Paris and a Free France…” K de B was reporting back to Simla via Peshawar weekly and was somewhat scathing about the masterly inactivity of the British Legation. who hardly ever ventured out of the vast compound. Pietro Quaroni the Italian Minister was a formidable opponent. But K de B with the help of his Pathan sidekick ( his Pathan ‘mother’s’ younger brother) did spike the German’s guns by passing on information which led to the ambush of two German Abwerh/Brandeburger agents trying to pass gold and weapons to the Faqir of Ipi. One was killed the other wounded. They did not try it again. And subsequently all the Axis legations and advisers were later thrown out of Afghanistan which quietened the NW Frontier down no end.

K de B was from a long line of Indian army officers and was also trained in naval codes and cyphers . Lt Cdr in RNR.

Interestingly K de B was allowed to examine at the Sorbonne. He also got on with Albert Foucher So Anglo French relations were not that bad at all.. at least between the V&A and the Musee Guimet.

Dear James,

I was interested to read your comment. I am completing my PhD on the politicization of archaeology in Afghanistan’s twentieth century history and would be delighted to hear more about your great uncle’s involvement in Afghanistan. If you’re willing, please feel free to contact me [personal details removed].

Best wishes,

Eva

Department of Archaeology

University of Cambridge