2017 marks the 500th anniversary of the beginning of the Protestant Reformation in Europe, with the promulgation of Martin Luther’s 95 theses. Martin Luther was an Augustinian friar and professor of theology at the University of Wittenberg. On 31 October 1517 he sent 95 theses – in other words, a list of propositions for academic disputation, criticising the sale of indulgences – to the Archbishop of Mainz.

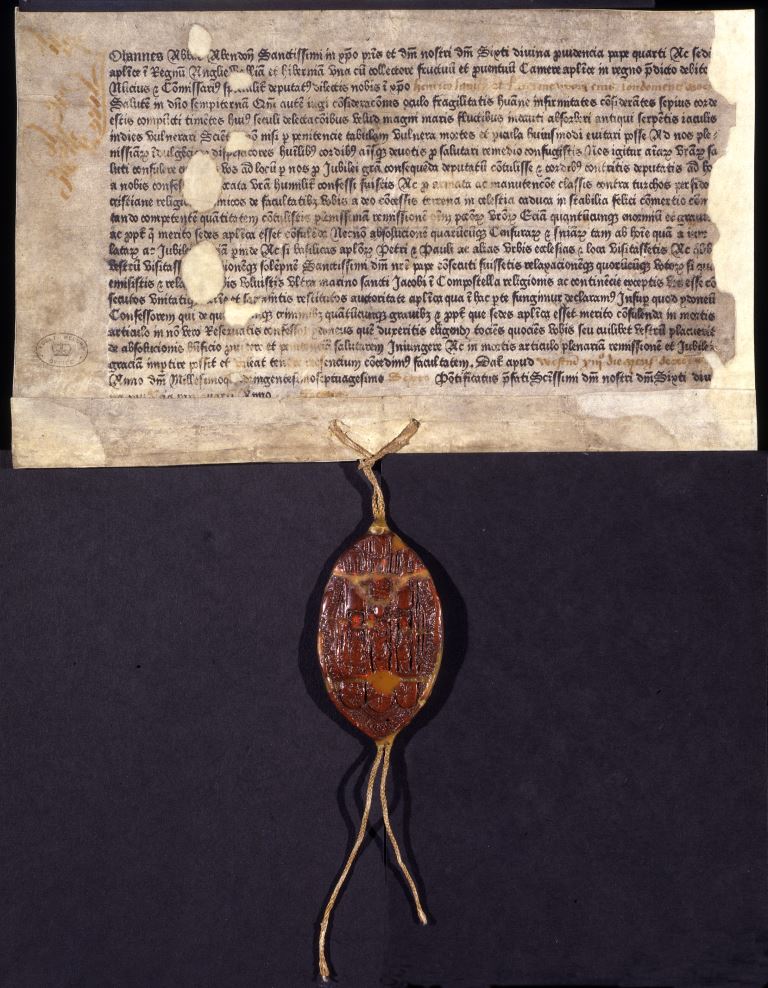

Indulgences could be purchased through support of Church causes in order to reduce the amount of punishment received in purgatory after death for remission for sins committed on earth. This was a popular practice advocated by the Church in late medieval Europe. We have some examples of indulgence certificates in The National Archives collections, including one which is the earliest surviving document printed by William Caxton (E 135/6/56).

Luther may also have posted his 95 theses on the door of All Saints’ Church in Wittenberg, as this was a standard way to announce a public debate at the time, but this is a contentious topic. In any case, the dissemination of his ideas resulted in a movement which developed into what we now refer to as the Protestant Reformation.

E 135/6/56: The earliest surviving document printed by William Caxton. An indulgence granted by John, abbot of Abingdon, to Henry Langley, and Katherine his wife, 1476

Part of my role in coordinating the Reformation Programme at The National Archives has involved networking with contacts across Europe. Back in March, I put on a display of some of our documents relating to the European Reformation for colleagues from the German Embassy. It is not widely known that The National Archives has holdings relating to the Reformation in Europe. Some of these treasures will be exhibited in the Keeper’s Gallery at the end of the month, and a forthcoming blog will explore these holdings in more detail.

Just as a teaser, a particularly interesting document from our collections relating to Luther is a report made on 2 February 1521, by Sir Thomas Spinelly to Cardinal Wolsey, on the early stages of the Diet of Worms (SP 1/21, fos 208-209v). Spinelly was Henry VIII’s ambassador to Spain in 1517-18 and he was then made Cardinal Wolsey’s agent in the Holy Roman Empire.

In this letter, Spinelly reports from Worms, as the Diet convenes, that Luther had demanded an audience before the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, to explain his publications and theology. The Diet was an assembly of the Holy Roman Empire held in the city of Worms. Prince Frederick III, the Elector of Saxony, who acted as Luther’s protector, and the Elector’s advisors, argued that Luther should not be condemned ‘unless he were heard first…so that the truth…could be brought to light’. 1

Luther had not yet been summoned by the Emperor to answer the charges of heresy that the Papacy had accused him of but this issue is obviously of some importance. The description that Spinelly used about the Emperor’s views is illuminating: ‘And us to Lutero (Luther), he esteemed that matter of great importance, and very difficile to be remedied and extincted’. 2

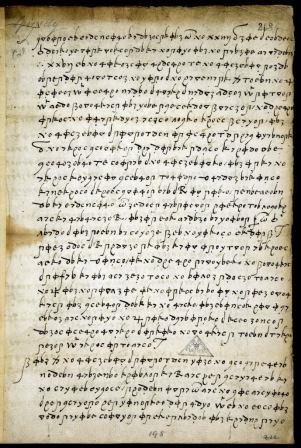

SP 1/21 f. 208: First page of a cipher letter from Sir Thomas Spinelly to Cardinal Wolsey, 2 February 1521

An interesting feature of Spinelly’s letter is that it was written in cipher. Cipher systems usually consisted of an alphabet, based upon alphanumeric or symbolic representation of the letters of the alphabet: these make the text impossible to understand without the key to the cipher.

Secret letters were a constant device employed in diplomatic correspondence from the early Tudor period and cipher alphabets were often found within the paperwork accompanying ambassadors on their missions. Each ambassador had his own cipher or multiple ciphers and the State Paper archives contain a vast number of ciphers.

There were many complications with the cipher system – ciphers were frequently updated, added to and supplemented – also often lost or stolen and needed replacing. No key is linked to this cipher but most likely the cipher was broken in modern times using contemporary decrypts of some of Spinelly’s other letters. 3

You can find examples of letters between Spinelly and Sir Brian Tuke, an administrator of Cardinal Wolsey who dealt with correspondence from ambassadors abroad, that have been deciphered, at the British Library. 4

On the basis of my contacts with the German Embassy, I was invited by the German Federal Foreign Office to a leading international conference in June. The purpose of the conference was to create dialogue between Reformation scholars and religious leaders from across the globe concerning the importance and legacy of the Reformation. There were delegates from fifteen countries, and I was pleased and privileged to find that I was representing not just The National Archives, but the whole of the United Kingdom. The visit involved a series of lectures, panel discussions, round tables and tours of pertinent exhibitions and historically significant sites.

Wartburg castle, Eisenach, Germany. The conference delegates visited this historic landmark, where Martin Luther translated the New Testament from Ancient Greek into German, which was published in September 1522

The group visited three national exhibitions created to commemorate the effects of Reformation on religion, education, language, culture and society across the world, from the sixteenth century up until the present day. I had the opportunity to discuss the development of our Reformation Programme with Dr Sigrid Bias-Engels, the Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and Media, who is overseeing over 1,600 Reformation-related events in Berlin this year alone. We also discussed the differences and similarities in the recording and presentation of the Reformation in our home countries at a special lunch in the Federal Foreign Office at the invitation of Michael Reiffenstuel, Deputy Director-General for Culture and Communication.

This conference highlighted why the Reformation is still relevant today: many aspects of modern-day society stem from changes that began in the sixteenth century. You can find out more about international perspectives on the Reformation anniversary from the conference participants here.

2017 is an important year for Reformation studies and particularly for The National Archives. We are holding a landmark conference on 3 and 4 November to celebrate and raise awareness of the incredible range of Reformation-related records that The National Archives holds. This conference will bring together scholars from across the UK, and further abroad, who are researching the Reformation using our documents. For more information about the conference programme, and to book, use our Eventbrite page. One of the fruits of the Reformation programme has been the creation of a research network and if you are interested in exploring the Reformation through the documents of The National Archives, please join our group.

Henry VIII and the break from Rome: an evening with Suzannah Lipscomb

Come and enjoy an evening with historian, broadcaster and award-winning academic Dr Suzannah Lipscomb, as she explores one of the fundamental turning points of the 16th century Reformation: Henry VIII’s separation from the Roman Catholic Church.

This special lecture will be accompanied by Tudor music and refreshments, and takes place on Friday 3 November at 18:00.

Notes:

- 1. L. Roper, Martin Luther, Renegade and Prophet (London, 2016), p 173. ↩

- 2. J S Brewer (ed), Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 3, 1519-1523 (London, 1867), p 430. ↩

- 3. J Daybell, The Material Letter in Early Modern England, Manuscript Letters and the Culture and Practices of Letter-Writing, 1512-1635 (Basingstoke, 2012), pp 148-165. ↩

- 4. For example, BL Cotton Vespasian C/I fos 265r-265v. ↩