‘I’ll be sworn ’tis true; he will weep you, an ’twere a man born in April’

Troilus and Cressida

‘Nor shall Death brag thou wander’st in his shade,

When in eternal lines to time thou growest;

So long as men can breathe or eyes can see,

So long lives this and this gives life to thee.

Sonnet 18

Portrait of Shakespeare, cat ref: PRO 30/25/205

You may have thought that 2012, the UK’s ‘Year of Shakespeare’, offered enough celebration of the life and career of the world’s greatest playwright, but Shakespearean scholars, students, directors, actors, audiences, readers and fans are preparing for two more exciting years of commemoration. The year 2014 marks the 450th anniversary of Shakespeare’s birth, usually assumed to have been on April 23rd 1564, three days before the first extant record of his life — his baptism at Holy Trinity Church in Stratford-upon Avon on April 26th.

The year 2016 will mark the 400th anniversary of his death on April 23rd 1616, which occurred, as one story relates, on the day after he had been out drinking in Stratford-upon-Avon with his old friends and fellow poets Ben Jonson and Michael Drayton. That the date of April 23rd apparently marks both his birth and death shows that Shakespeare’s sense of timing was as impeccable in his life as in his plays.

While some have argued that there are very few contemporary records of Shakespeare’s life, there is much more documentation of his life than for the average citizen of 16th- and 17th-century England, as well as for most of his contemporary writers. In an age without centralized or cross-referenced records, people’s lives were usually documented in terms of their own and their relatives’ births, marriages and deaths in their local parish church registers. Other documentation came in legal paperwork for mortgages, wills or property purchases or leases, for example, and in depositions for court cases (often in disputes about mortgages, wills and property). Other documentation appears in censuses and similar records, including sacramental token-books, which listed the names of heads of household in a parish. Prof. William Ingram and Prof. Alan H. Nelson recently launched a database of the token-books dating from the 1570s to the 1640s of London’s St Saviour’s parish church, which after some enlargement became Southwark Cathedral in 1905. These token books give us an invaluable look at an early modern community at the heart of London’s theatre world.

St Saviour’s, in close proximity to the Southbank’s playhouses, including the Globe and the Rose, was the parish most commonly associated with actors, playwrights, and other theatre personnel. The theatrical entrepreneur Philip Henslowe and his son-in-law, the great tragedian Edward Alleyn, were vestrymen at St Saviour’s and conducted many business deals with other parishioners. Henslowe is buried near the altar, while Alleyn is buried at Dulwich College Chapel, which he founded along with Dulwich College and numerous almshouses. Also buried in St Saviour’s church are the playwrights (and Shakespeare’s colleagues) Philip Massinger and John Fletcher, and the actor Edmund Shakespeare, whose burial in 1607 was almost certainly paid for by his brother, William Shakespeare.

Whilst the registry record of Shakespeare’s birth is held in Stratford-upon-Avon and his November 28th 1582 marriage bond to Anne Hathaway is now in Worcestershire Record Office, a series of important records of his life are held at The National Archives, [ref] 1 For a full list and transcriptions of The National Archives and other documents recording Shakespeare’s career, see the excellent book English Professional Theatre, 1530-1660, edited by Glynne Wickham, Herbert Berry and William Ingram. For biographical information about Shakespeare, see the still-influential books by Samuel Schoenbaum: Shakespeare’s Lives and William Shakespeare: A Documentary Life. [/ref] including pleadings and depositions in three lawsuits in the Court of Requests involving Shakespeare.

As noted in The National Archives’ Discovery catalogue, these include:

- the case of Belott versus Mountjoy, which concerns a marriage dowry and contains Shakespeare’s signed deposition. The documents pinpoint his residence in 1604

- the case of Keysar versus Burbage and others, which describes the King’s Men acting company’s involvement in the Blackfriars Playhouse

- the case of Witter versus Heminges and Condell, which describes the way in which the shares in the syndicate that leased the Globe playhouse were distributed

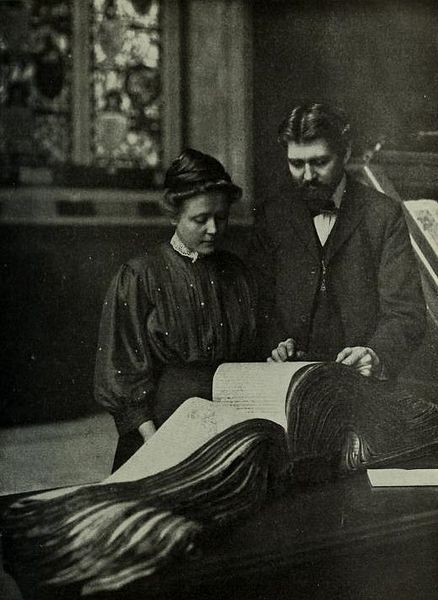

Professor and Mrs Charles William Wallace, Wikimedia (copyright expired)

In fact, in the early 20th century, Charles William Wallace, an American professor, and his wife Hulda discovered these documents, among many others, among un-catalogued papers at the Public Record Office (the former name of The National Archives) in Chancery Lane. Other Wallace finds included payments to the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, and later as the King’s Men, for performance at court and elsewhere, that are recorded in a range of documents at The National Archives.

Prof. Wallace’s own archive, which is held at the Huntington Library in San Marino California and on which I have worked, contains Hulda Wallace’s painstaking, handwritten transcriptions of their astonishing research among thousands of pages of papers at the Public Record Office. The Wallaces spent many years reading through every 16th– and 17th-century document available and searching carefully for the names of people associated with professional theatre in London and the provinces.

Wallace’s correspondence in his archive bitterly demonstrates the ways in which his invaluable discoveries were ridiculed or marginalized for many years by leading British scholars of Shakespeare, some of whom disingenuously claimed to have already found the most important documents (but somehow had failed to publicize these discoveries). One leading British scholar of the time, who shall remain nameless, even claimed to the press that Americans were not intellectually capable of such research (I found this very interesting, as I am an American scholar who specializes in archival research of Shakespeare and his contemporaries).

The documents located by the Wallaces at the Public Record Office are not as substantial or wide-ranging as the exceptionally large collection of the Henslowe-Alleyn papers held at Dulwich College (which I digitized). But the Public Record Office documents share the distinction with the Henslowe-Alleyn papers of being the foundational records of Shakespearean and early modern English theatre history. Without the dogged determination, patience and courage of the Wallaces, these Public Record Office/The National Archives’ records might still be waiting for use and attention, and we would know much less about the workings of the theatre industry that produced Shakespeare and his colleagues.

Other documents at The National Archives reveal the growing status and prestige of Shakespeare, as, for example the 1604 Progress of James I through the city of London, which mentions a grant of cloth to Shakespeare.

But of course the major Shakespearean treasure at The National Archives is his will, dated March 25th 1616, which contains three of the only surviving six examples of his signature. The will uses a conventional legal format of the age and begins,

In the name of god Amen I William Shackspeare of Stratford

upon Avon in the countie of Warr’ gent in perfect health &

memorie god by praysed doe make & Ordayne this my last

will & testam[en]t in manner & forme followeing That ys to

saye first I Comend my Soule into the hands of god my

Creator hoping & assuredlie beleeving through thonelie

merittes of Jesus Christe my Saviour to be made partaker of

lyfe everlastinge And my bodye to the Earthe whereof yt ys

made.

Shakespeare left £150 to his daughter Judith but left his estate, including his house New Place, to his two executors: his other daughter, Susannah, and her husband John Hall. Shakespeare also made bequests to his other relatives and to friends, including 26 shillings and 8 pence each to his former King’s Men’s colleagues and “ffellowes John Hemynges, Richard Burbage & Heny Cundell” in order “to buy them Ringes”. He left the poor of Stratford a generous £10. A full transcription of the will can be found on The National Archives’ website.

Shakespeare stipulated that his wife should receive his ‘second best bed with the furniture’. Although many have argued over the years that this was an insulting bequest, it is entirely possible that Shakespeare had already explained to his executors how to use his estate for the benefit of his wife, who may not have been in a position to act as an executor. Indeed the bequest to Anne may be a private message that she would understand, perhaps with the ‘second best bed’ being the one that they had shared during the marriage and thus a sentimental reminder of their life together.

Scholars will celebrate in 2014 the anniversary of Shakespeare’s birth with a major conference in Paris, among other places, and in 2016 will commemorate the anniversary of his death with the 10th World Shakespeare Congress in Stratford-upon-Avon and London. Exhibitions and special performances and events will also be held in 2014 and 2016 at museums, libraries and theatres for all those interested, whether they consider themselves to be scholars or not. For example, the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust has a series of exciting birthday events planned.

In addition, a consortium of US and UK libraries and archives, including The National Archives, will contribute to a travelling exhibition of manuscripts and books associated with Shakespeare’s life and career. The launch in 2014 of the Sam Wanamaker Theatre at Shakespeare’s Globe is also a wonderful testament to the ways in which Shakespeare will always remain the most modern of writers 450 years after his birth and 400 years after his death.

In Twelfth Night, Shakespeare seems to enjoy mocking the ill-tempered Malvolio by having him read aloud the statement, “Be not afraid of greatness: some are born great, some achieve greatness, and some have greatness thrust upon ’em”. Surely we can say that Shakespeare did achieve greatness, and in 2014 and 2016 we can emphasize that fact by thrusting further greatness upon him.

A recent television programme raised considerable doubt amongst some researchers as to whether he did or could have written the works attributed to him, particularly over the events in the Royal Court and that his family could not write their names. The programme was pretty convincing.