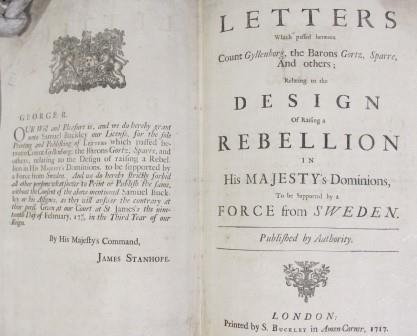

Published letters of Count Gyllenborg, Barons Görtz and Sparre, and others (catalogue reference: SP 9/251/222)

300 years ago, ambassadors at the Swedish Foreign Ministry attempted to foment an invasion plan and embark a force for the British Isles, in support of the Jacobite Pretender’s claim to the throne.

In 1716, after James Francis Stuart had left Scotland, the Swedish envoys in London and Paris, Carl Gyllenborg and Count Sparre, plotted with Jacobite agents to secretly loan money to Charles XII (last of the Vasa kings in Sweden) in exchange for Sweden’s help in a new Jacobite enterprise against the Hanoverian King George I. In Britain, as intercepted Jacobite correspondence testifies, rumours circulated that James, commonly referred to as the Old Pretender, had been offered money and 12,000 Swedish soldiers by France.

Britain’s interests were far larger than those of Hanover. British statesmen and diplomats sought world trade domination and colonial expansion, while Hanover mostly sought the acquisition of Swedish territories in north Germany. The electorate of Hanover itself, moreover, had been an anti-Swedish ally of both Russia (under Peter the Great) and Denmark-Norway during the Great Northern War.

While Swedish diplomatic designs were initially anti-Hanoverian (rather than pro-Jacobite), Ambassador Gyllenborg kept in touch with crypto-Jacobite MPs in London in a Machiavellian attempt to reverse the fortunes of Sweden as a declining maritime power. Gyllenborg was an able and respectful diplomat, having done his best to foster the help of any MP sympathetic to the Swedish cause, or merchant who feared Russian rivalry in the ‘Eastland’ carrying trade; he also appealed to public opinion by pamphleteering.

As ministerial representative of the Swedish legation, Gyllenborg had earlier married the politically active Tory, Sarah Wright. As a known Jacobite sympathiser, Wright used her wealthy connections to attempt a coup on behalf of the exiled Stuart claimant. A project to assassinate King George’s Cabinet and kidnap the royal family was directed by Lord Oxford, then in the Tower awaiting impeachment. Other High Tories implicated in the plot included Francis Atterbury, Bishop of Rochester, whom the Pretender made his chief representative in England, and Lord Bathurst, who alone contributed £1,000 (over £80,000 today) to the invasion fund.

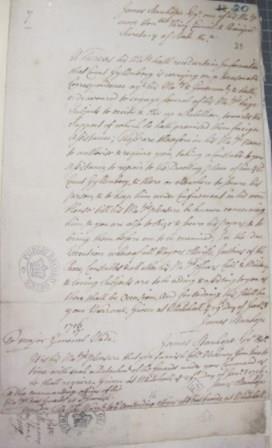

Warrant to Major-General Wade for the arrest of Count Gyllenborg (catalogue reference: SP 35/8/20)

Speculation began in the autumn of 1716 when overtures were made by Gyllenborg, promising a force of 10,000 Swedes. Hanover had one of the most advanced intelligence services and the British were fully aware of these Jacobite agitations. The government of George I seized the moment to intervene.

Before the northern question –the balance of power in the Baltic region – could be brought to Westminster, Gyllenborg was arrested in London on 29 January 1717 by George Wade.[ref]1. The future Field-Marshal and military road builder in North Britain.[/ref] Following the protests of the ambassadors of Spain and Holstein, George I’s chief ministers the Earl of Sunderland and Lord Stanhope made public incriminating documents during the trial. Count Görtz (Gyllenborg’s superior at The Hague) was at the same time arrested in Gelderland, on a charge of undermining the Protestant succession. The fact that the United Provinces as well as Britain were at least by treaty allies of Sweden (even though Hanover was at war with Sweden), made these events sensational.

The government, disregarding international law, seized Gyllenborg’s papers. They were laid before Parliament, showing that English Jacobites had undertaken to raise upwards of £20,000 to be sent abroad. A fleet under Sir George Byng was dispatched to the Baltic (see SP 35/8/83), following an embargo placed on trade with Sweden.

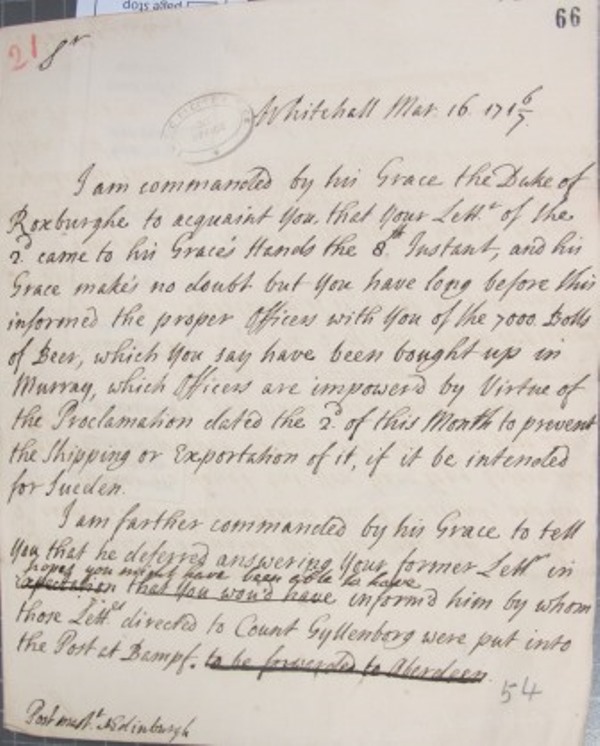

Prevention of the exportation of beer from Scotland to Sweden (catalogue reference: SP 54/13/21)

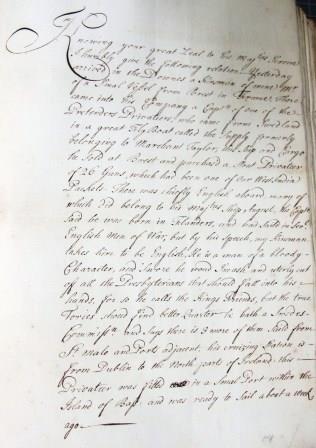

Allegations against an English Tory privateer captain out of St Malo, ‘having served the Pretender in Swedland would utterly smash all the Presbyterians’ (catalogue reference: SP 42/16/80)

British ministers authorised these actions to prevent the flagrant breach of the (1701) Act of Settlement by directly involving Britain in a war on behalf of Hanover’s interests. The whole affair would become a quest to safeguard the Anglican Church from the Catholic House of Stuart, which was seen to be supported by Lutheran Sweden (who in turn had been traditionally financed by France). Meanwhile Swedish privateers menaced British mercantile shipping on the high seas, and were consequently very often manned by British or Irish Jacobite crew members.

The publishing of these diplomatic secret documents was positively explosive, considering that the usual practice of the times was to ask for a ministerial recall, and generally excluded the confiscation of state papers. The bellicose Charles, though outraged, told the French Regent (Philippe of Orléans, who was mediating the crisis) that at no time did he have any intention of offending Great Britain. He had in reality sent Görtz to Holland to seek Jacobite monetary aid. Moreover, such shadowy figures as (the financier and freemason) Emanuel Swedenborg, would also engage the services of the (largely English) Jacobite pirates of Madagascar on behalf of the Swedish crown (see SP 42/17/9).

By 1717 rumours had contributed to a sense of crisis. In February, it was reported from Rotterdam that there was a danger of the Jacobites invading Scotland from Sweden (a report based on Danish intelligence under the formidable Commodore Tordenskjold at Stavern).

In the spring, it was also reported that Sweden was mustering a force of 12,000 troops at Gothenburg (see SP 42/16/65) that was to land at Bridlington Bay. The government was determined to use the Gyllenborg affair in order to secure a definitive parliamentary commitment to support George I’s anti-Swedish policy.

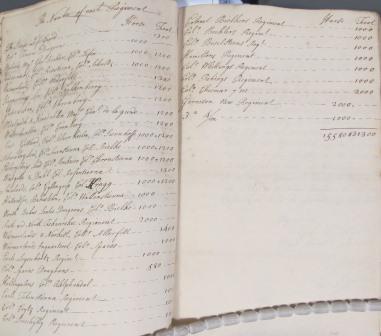

- ‘Disposition of Swedish troops’, April 1717 (catalogue reference: SP 42/16/66)

- Dano-Norwegian intelligence report (catalogue reference: SP 42/16/57)

The Whig politician Robert Molesworth, even claimed that, ‘there’s not a Jacobite schoolboy or poor tradesman’s wife…who has not been instructed how conveniently Norway lies to Scotland, and how much of it was in their master’s interests that the brave King of Sweden should succeed in his undertakings.'[ref]2. J. Black, ‘Politics and Foreign Policy in the Age of George I, 1714-1727’ (Aldershot, 2014), 81.[/ref]

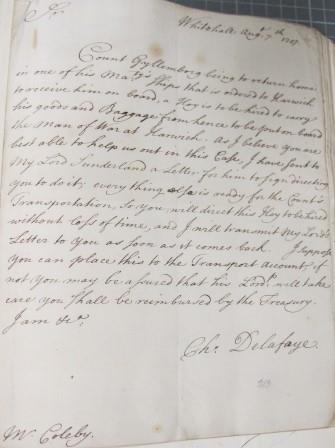

Order to transport Gyllenborg ‘back home aboard a man-of-war with all his goods and baggage’, 7 August 1717 (catalogue reference: SP 42/16/97)

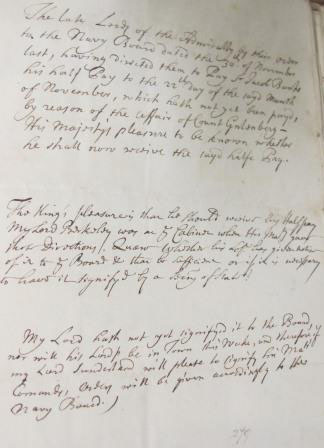

Authorisation to continue Bancks’s naval pension (catalogue reference: SP 42/16/127)

Since the arrested diplomats were eventually exchanged, Gyllenborg and the implicated Navy Board Secretary Jacob Bancks, were ironically both awarded financial settlements by Parliament. George I for his part, hoped that these acts of courtesy would prevent a separate peace between the northern rulers, and a Stuart alliance with the Russian Empire.

Although Charles XII was to be killed (at Fredrikshald in 1718), the Jacobites, as ever, did not become disillusioned and continued plotting, this time by turning to the support of Bourbon Spain.

The ‘Swedish’ invasion was at best an illusionary scare (a ‘splendidly convenient’ excuse by the Hanoverians to wage war against the non-sovereign House of Stuart). However, much might have been made of this opportunity, save the strength of the Anglo-Danish alliance and the untimely death of Charles in his Norwegian siege lines aged 36.

Good story, it is always good to know about these events because they fill you with new information.

Interesting. I never knew Sweden was involved in the wars for the British throne. I thought they were mostly active in Northern Germany, Poland and the Baltic states.

Peter many thanks for your comments

Although it is true that Sweden was primarily interested in territorial expansion across the Baltic and northern Europe, the Vasa dynasty was particularly linked to British foreign affairs in the seventeenth century, as Gustavus Adolphus heavily recruited Scots mercenaries during the Thirty Years War. While Queen Christina would personally favour the Royalist cause during the Civil War, a diplomatic embassy from the English Commonwealth was invited to Uppsala in 1653 to secure an Anglo-Swedish maritime alliance against the Dutch.

Very much appreciate your interest

Very interesting story, clearly explained.

Thank you for this well-written and intriguing analysis of your research.

Can you elaborate on why you connect Swedenborg to the citation for the Madagascar situation? The link goes to a general description of the two documents but Swedenborg is not mentioned. I’m curious as to why you indicate him. My second and probably related question is whether you follow Schuchard’s scholarship on Swedenborg and the Jacobite project, which she believes continued for him well into at least the middle of the 18th century. I know your interests are centered around England and not Sweden or Swedenborg, but am curious whether Schuchard has been a useful scholar for your thinking on the Swedish-Hanoverian connections around 1720.

I thank you Jim for your comments.

While I only came across the intriguing character of Swedenborg in my wider research (who Schuchard for example links to pro-Jacobite secret activities), I actually cited that particular document as it illustrates the presence of English (as well as French) corsairs in Madagascar and the Indian Ocean at that time.

Appreciated

According to Voltaire, the plan was actually modeled upon William of Orange’s own (successful) coup against his father-in-law James VII & II and required 12,000 cavalry officers. The negotiations in France, with Louis XIV, also revolved around William III (as a point of pride, since he had accepted James VII & II, in exile, partly due to his hatred of William, whom had defeated his French armies in Holland in winter) and this is also how the Jacobins, ironically, end up in France (Jacobins is the French way of saying Jacobite, which itself is Hebrew for James). Caspar Von Bothmer, Hanoverian ambassador, confidant to Queen Anne, letter burner, resident of 10 Downing intercepts the letter from von Görtz to the Tories, ending the plot.

Von Görtz is let go, only to be arrested, tried and found guilty for crimes against the state, back home, in Sweden, a couple of years later, for… issuing paper money not backed by gold. This is shortly after the King is killed, shot in the head, at close range, under mysterious circumstances perhaps by his best friend and sister’s lover, who himself goes insane as the sister ascends to the throne. Charles had bankrupted the treasury at war with Peter the Great for twenty years and even as the Turks held them both hostage for ransom [see also: The Genuine Letters of Baron Fabricius], the Turkish Caliphate’s Grand Vizier ended up sending him home loaded with cash on his promise he would end his war with Peter. During this period, Charles is negotiating with the Swedish Pirates of Gothenburg, to grant them reprieve and citizenship in exchange for their gold booty treasure loot replenishing the empty Swedish coffers. And it’s one of their ships he is trying to buy to move the 12,000 cavalry soldiers and horses, a Dutch ship which he is looking for the French to pay for. But, due to the nature of privateers, the ship instead ends up impounded in 1716, subject of a lawsuit in 1717, and in Madagascar by 1718.