On Tuesday 28 July, exactly one month after the assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand, Austria declared war on Serbia. At 4.15 pm the Foreign Office received a telegram from Dayrell Crackanthorpe, Britain’s Chargé d’Affaires in Belgrade. The Austrian Minister had left the city and an immediate attack was expected.

At 7.20 pm, a further telegram from Sir Maurice de Bunsen, the British Ambassador in Vienna, confirmed that war would be declared that day. Later, Austrian artillery began shelling Belgrade across the Danube and negotiations with Russia fell apart.

Some in Britain already feared the worst possible outcome. Sir Arthur Nicolson, Permanent Under Secretary of State, and his assistant Sir Eyre Crowe, were convinced that Germany intended to attack Russia and France. Only strong British support for France could ward off German aggression. Britain had earlier agreements to guarantee the neutrality of Belgium and to defend the northern French coast.

That night, Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty, wrote to his wife, ‘My darling one and beautiful, everything tends towards catastrophe and collapse’. On the morning of 29 July, The Times reported that the Russian authorities had ordered the extinguishing of all lights along the Russian Black Sea. Sevastopol was closed to all ships apart from the Russian Navy and the German fleet was mobilising.

Nevertheless, there was still a note of guarded optimism. Sir Edward Grey, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, believed that negotiation with Germany might still avert a general war. The Times also reported that the attitude of the German government was still undecided and it was thought that the German Emperor wanted peace.

Cabinet deliberations

The Cabinet met at 11.30 on 29 July. The events of the previous day had changed the terms of debate. It was no longer a question of if there would be war, but of what Britain should do. Grey, perhaps moving to a more interventionist stance, asked the Cabinet to decide if Britain would enter the war in support of France, should that become necessary. But there were deep divisions in the Cabinet. Some of the Liberal members, like John Burns, President of the Board of Trade, were strongly against war. In the end, nothing definite was decided. Britain could not at that time pledge military support for France. But Churchill obtained permission from the Prime Minister Henry Asquith to send the Navy to battle stations. Britain seemed to edge closer to war.

After the Cabinet meeting, Grey spoke to the French Ambassador, Paul Cambon, telling him the outcome. Next he conferred with Prince Lichnowsky, the German Ambassador. In this case, he went further than the remit given him by Cabinet. He warned him in a ‘friendly’ way that if Germany became directly involved in the conflict, Britain might be forced to intervene if its interests were threatened. Lichnowsky duly reported back to Berlin. The German Chancellor, Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg, was shocked by the news, as he had been counting on British neutrality. He made a last ditch, but unsuccessful attempt to persuade Austria to accept mediation (FO 371/2159 paper 35001).

The German proposals

On that same day, Sir Edward Goschen, the British Ambassador to Berlin, was asked to call on the Chancellor. Bethmann-Hollweg told Goshen that if Russia attacked Austria, a ‘European conflagration’ was inevitable, but he hoped that Britain would remain neutral. It was not Germany’s aim to ‘crush’ France and no French territory would be seized, though he could not promise the same for France’s colonies. As for Belgium, he was unable to say what military operations might be necessary there, but as long as it did not side with France, Belgium’s integrity would be respected. It seemed evident that Germany was set on war with France.

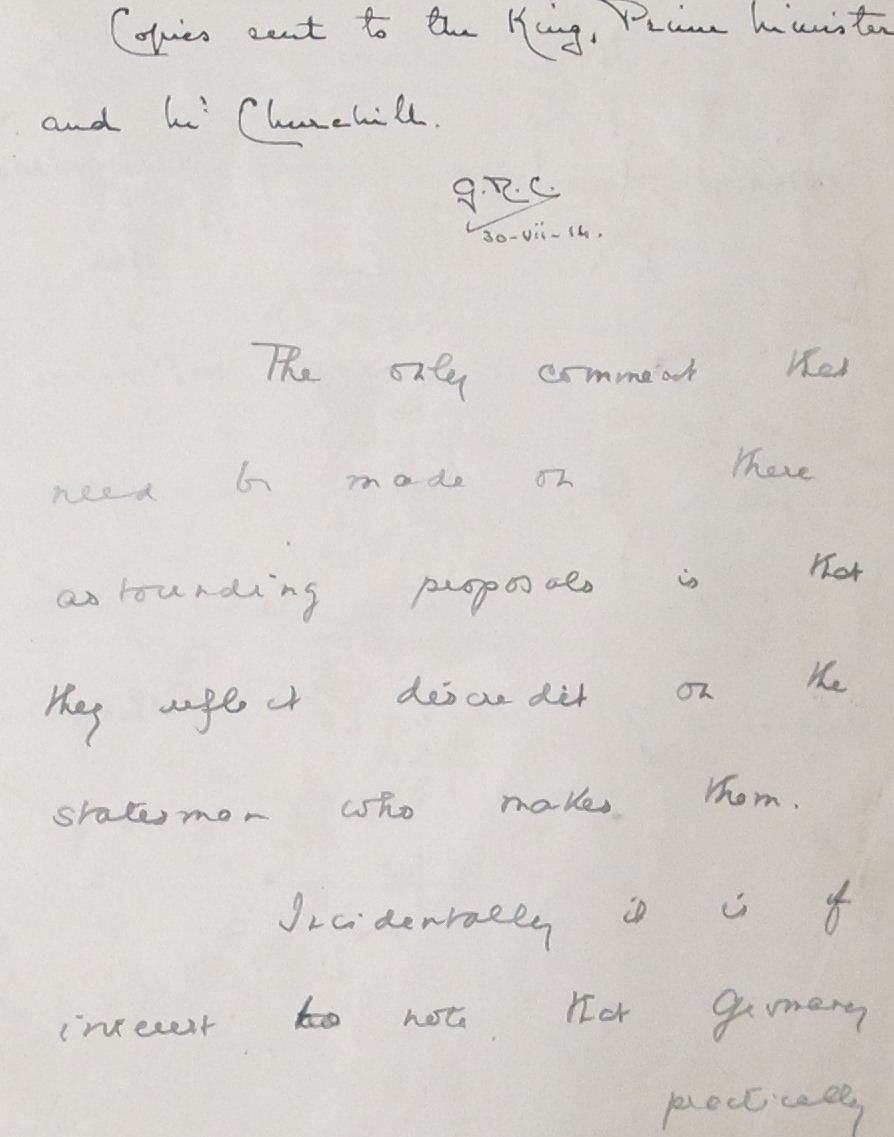

Bethmann-Hollweg’s approach met a hostile reception at the Foreign Office, where it was discussed the next morning, Thursday 30 July. Eyre Crowe noted that ‘The only comment that needs to be made on these astounding proposals in that they reflect discredit on the statesman who makes them’. He concluded that ‘Germany is practically determined to go to war’ held back only by ‘the fear of England joining in the defence of France and Belgium’ (FO 371/2159 paper 34734).

Grey too was infuriated. He wrote immediately to Goschen, who was to tell the German Chancellor that his proposals were unacceptable. To accept them would be ‘a disgrace from which the good name of this country would never recover’. Nevertheless, he still thought that Britain should keep its options open and that negotiation with Germany was the best course. (FO 371/2159 paper 34734)

French demands

Meanwhile, Cambon had been working hard to persuade senior Foreign Office staff to pledge support to France against a German attack. Following another inconclusive Cabinet meeting on 31 July, Grey and Cambon again met. Grey pointed out powerful commercial and financial pressures against Britain entering a war and told Cambon that Cabinet ‘could not give any pledge at the present time.’ On the other hand, he seemed to offer him some hope. He had, after all, refused the German Chancellor a promise of neutrality and the independence of Belgium remained an important factor (FO 371/2159 paper 35146 and FO 371/2160 paper 35370).

But control was slipping away from the politicians into military hands. By the 31 July, Germany, Russia and Austria had ordered general mobilisation. The vestiges of optimism had faded. On that morning, The Times envisaged a ‘terribly automatic war’ in which ‘one thing leads to another, as with a line of tin soldiers if one is knocked over, the next falls down in turn, so may the powers, one by one, dreading and detesting war as they do, be dragged into it’. It would be another three days before Britain declared war, responding to the German invasion of Belgium.

Further reading

Ekstein, E K & Steiner, Z, ‘The Sarajevo Crisis’, in Hinsley, E H, (ed.), British Foreign Policy under Sir Edward Grey (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1977.

MacMillan, M, The War that ended Peace (Profile Books, London, 2013)

Gooch, G P & Temperley, H, British Documents on the Origins of the War, 1898-1914, Volume XI, The Outbreak of War: Foreign Office Documents, June 28th – August 4th 1914 (HMSO, London, 1926) and online.

First sentence say was declared August 28. That is incorrect.

[…] 100 years ago today: Austria declares war on Serbia […]

thank you for 100 years ago today: Austria declares war on Serbia !!

For the first time in my entire life, a typo has been corrected. Thank you, former Mother Country, for restoring my faith in Great Britain.

I was under the impression that it was the Austrian-Hungarian Empire that declared war and not just Austria.

Hi David,

Thanks very much for pointing this out, we’ve made that correction.

Alexa on behalf of the blog

Hello David

Your comment on the Austrian-Hungarian Empire is perfectly correct. There was a constitutional union between Austria and Hungary, which lasted until 1918. But following some texts and for the sake of brevity, we decided to use ‘Austria’.

Daniel