This blog continues our series commemorating the centenary of the Battle of Arras.

In the days following the battle of Vimy Ridge, newspaper headlines throughout the allied countries proclaimed that Canada’s soldiers had captured an objective that had long-seemed impossible. Families of those in uniform greeted the news with excitement and worry; as one father wrote to his son who had fought at Vimy: ‘The press are giving the Canucks great praise. They certainly had the place of honour, but according to the casualties, they are paying a price for it.’ Over 10,000 Canadians had been killed or wounded.

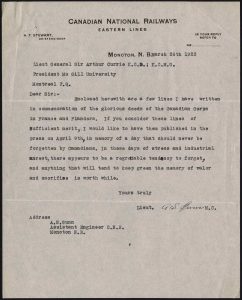

- Letter from Angus Stirling Gunn to Lieutenant-General Sir Arthur Currie, March 26, 1923. Gunn, a First World War veteran, hoped that Currie would help get his poem published in Canadian newspapers on the 4th anniversary of the Battle of Vimy Ridge. Currie papers, vol. 9, file 28. (Library and Archives Canada, MIKAN 4939490)

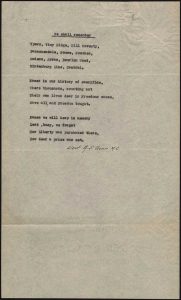

- Poem from Angus Stirling Gunn to Lieutenant-General Sir Arthur Currie, March 26, 1923. Gunn, a First World War veteran, hoped that Currie would help get his poem published in Canadian newspapers on the 4th anniversary of the Battle of Vimy Ridge. Currie papers, vol. 9, file 28. (Library and Archives Canada, MIKAN 4939490)

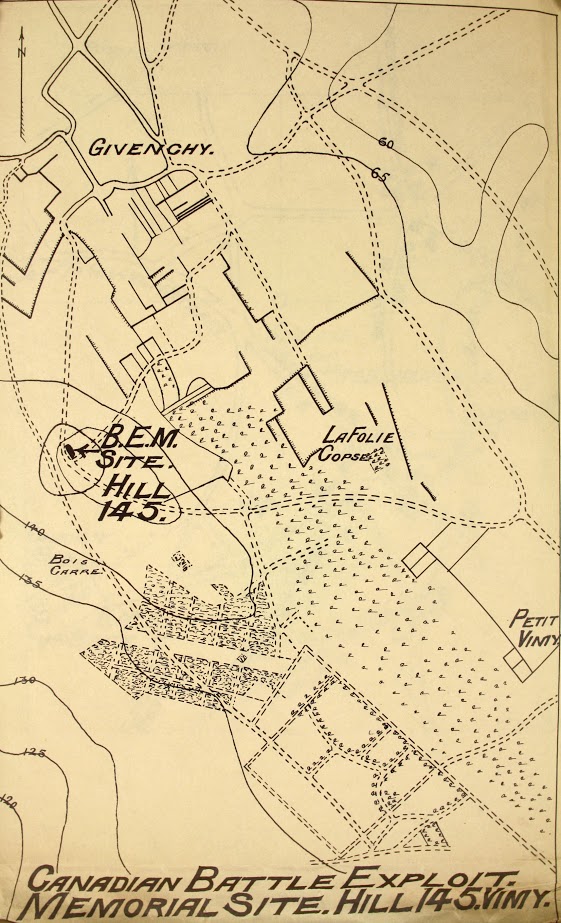

Map of the proposed site of the Vimy memorial, undated. (The National Archives, WO 32-5861)

An immense sense of pride about this all-Canadian victory was felt by those who had fought at Vimy, their families, and civilians. The battle almost immediately became a symbol of Canada’s emerging nationhood. The battle’s first anniversary was marked with fundraising drives, and by the end of the war many Canadians believed that France was planning to give Vimy Ridge to Canada in grateful tribute to this military triumph. Over the following years, the battle’s anniversary was marked by banquets, concerts, and church services on what was known as ‘Vimy Ridge Sunday.’ Towns, streets, parks, businesses, and lakes throughout the country, as well as a mountain and quite a few babies were named for the battle, becoming ever-present reminders of what Canadians had achieved in 1917.

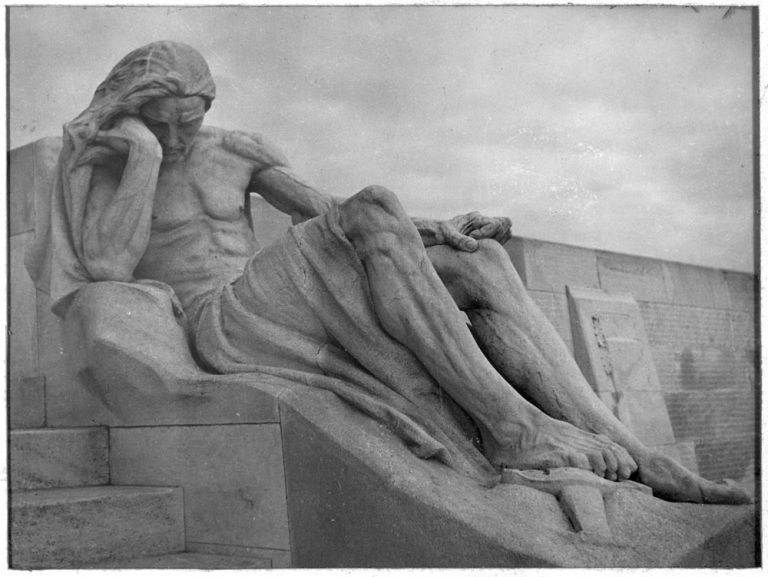

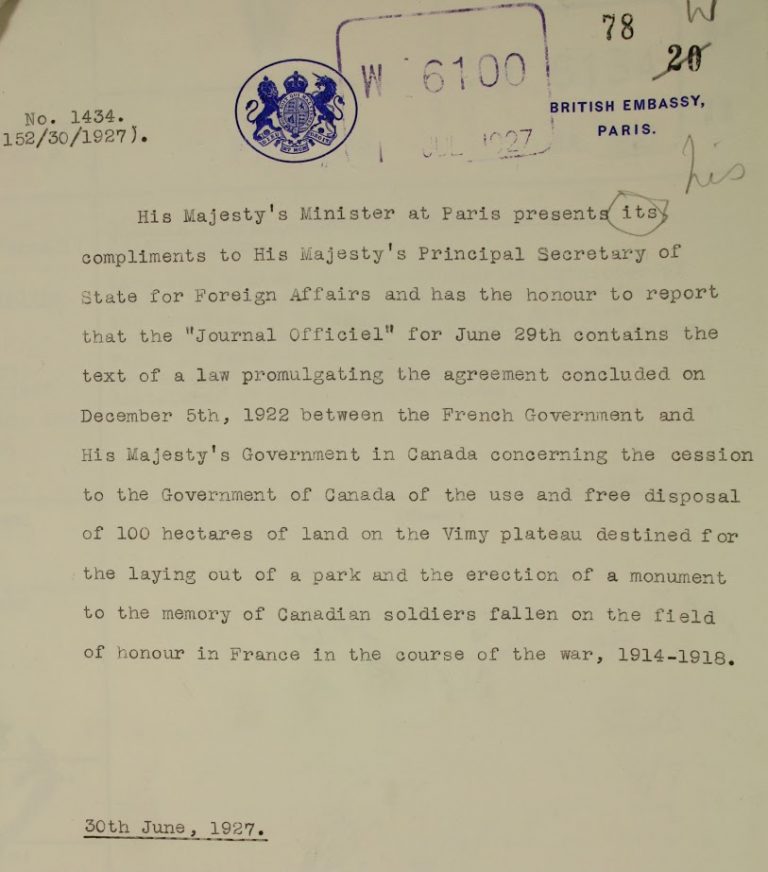

Amid this widespread commemoration, in October 1921, the federal government chose Toronto sculptor Walter Allward to design the Canadian National Vimy Memorial that now commands Vimy Ridge’s highest and most important feature, situated on land given to Canada by France. Over the next 15 years, the ground was cleared of unexploded shells, bombs and grenades and landscaped, a system of trenches was preserved and the memorial was erected.

In the late 1920s, veterans groups began planning a pilgrimage of those who had fought at Vimy and their next of kin to ensure that a large Canadian contingent would attend the memorial’s dedication ceremony. In July 1936, over six thousand pilgrims boarded five specially chartered ocean liners in Montréal. Pilgrims were given distinctive berets and badges and told that they were Canada’s ambassadors to Europe. For many British-born pilgrims, the voyage was also an opportunity to visit their families, which had been one of the allures of joining the Canadian Expeditionary Force two decades earlier.

One of the statues on the Vimy Memorial. (Library and Archives Canada, MIKAN 3329415)

Letter confirming the transfer of land in France to the Canadian Government, June 30, 1927. (The National Archives, FO 371/12638)

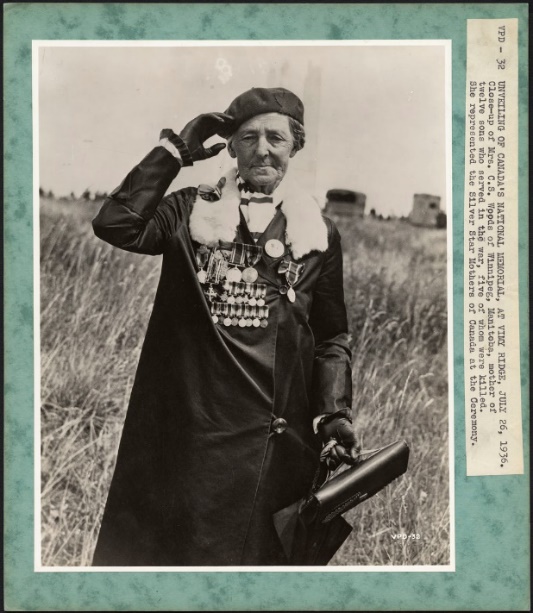

Among the pilgrims was Charlotte Wood, who had immigrated to Alberta from Chatham, Kent, England in 1904. Eleven of her sons and step-sons had served in uniform. Five of them had been killed, including Peter Percy Wood who had died near Vimy Ridge shortly after the battle. He has no known grave and is among more than 11,000 Canadians declared missing and presumed dead in France, and whose names are inscribed on the memorial. Mrs. Wood was the first Silver Cross Mother, a woman chosen annually to represent all Canadian mothers who have lost children in the service of the country. The Japanese-Canadian community also sent two representatives to commemorate the members of the community who had served during the war.

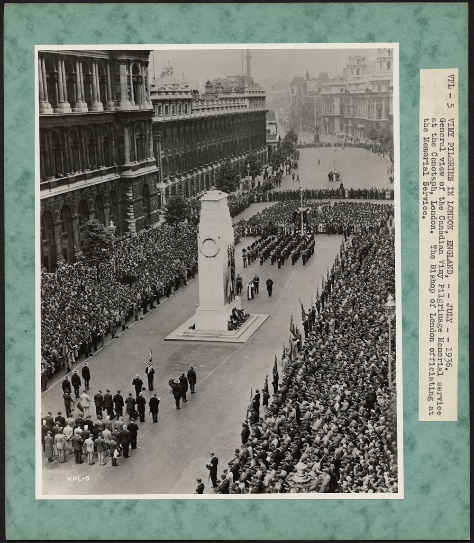

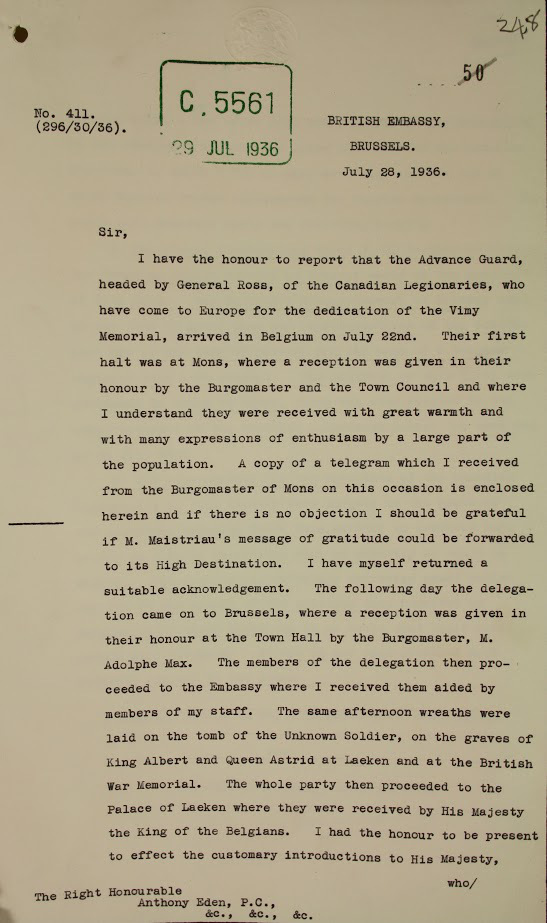

The pilgrims first disembarked in Antwerp, Belgium where they boarded buses that carried them past First World War battlefields and cemeteries to Vimy Ridge. The memorial was dedicated by King Edward VIII on July 26, 1936 before a huge crowd of pilgrims, veterans from many nations, military personnel and dignitaries. The King was very popular in Canada and even owned a ranch in Alberta. The pilgrims then sailed to London where they laid wreaths at the Cenotaph in Whitehall. These veterans were now in London as the representatives of a country that had gained significant autonomy since the war. The pilgrimage concluded in Paris where wreaths were laid at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier.

- Vimy pilgrims at the Cenotaph, Whitehall, London, July 29, 1936. (Library and Archives Canada, MIKAN 4939444)

- Charlotte Wood at the Vimy Ridge Memorial, July 26, 1936. (Library and Archives Canada, MIKAN 3224323)

In 1940, the Vimy Memorial’s Canadian caretaker was captured by German forces as they overran northeastern France at the start of the Second World War. Rumours abounded throughout the war that the memorial had been damaged or destroyed. On September 11, 1944, Lieutenant-General Harry Crerar, who had fought in the battle of Vimy Ridge and now commanded the First Canadian Army, made a highly publicized visit to this symbol of national military strength. Photographs of his visit proved that the newly liberated memorial was in remarkably good condition, thanks in large part to Paul and Alice Piroson, a Belgian couple who had looked after it throughout the war.

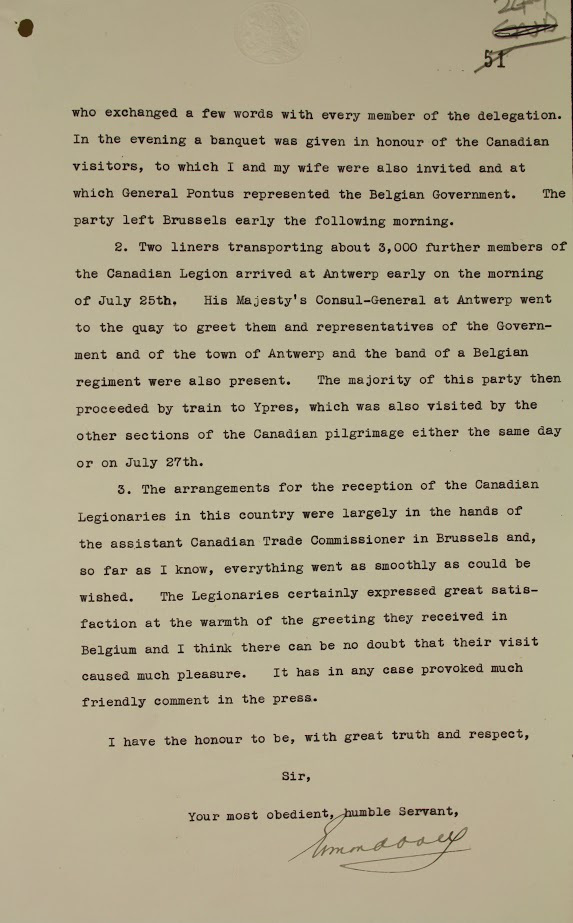

- Letter from the British Embassy in Brussels regarding Canadians visiting for the Vimy dedication, July 28, 1936. (The National Archives, FO 371/19877)

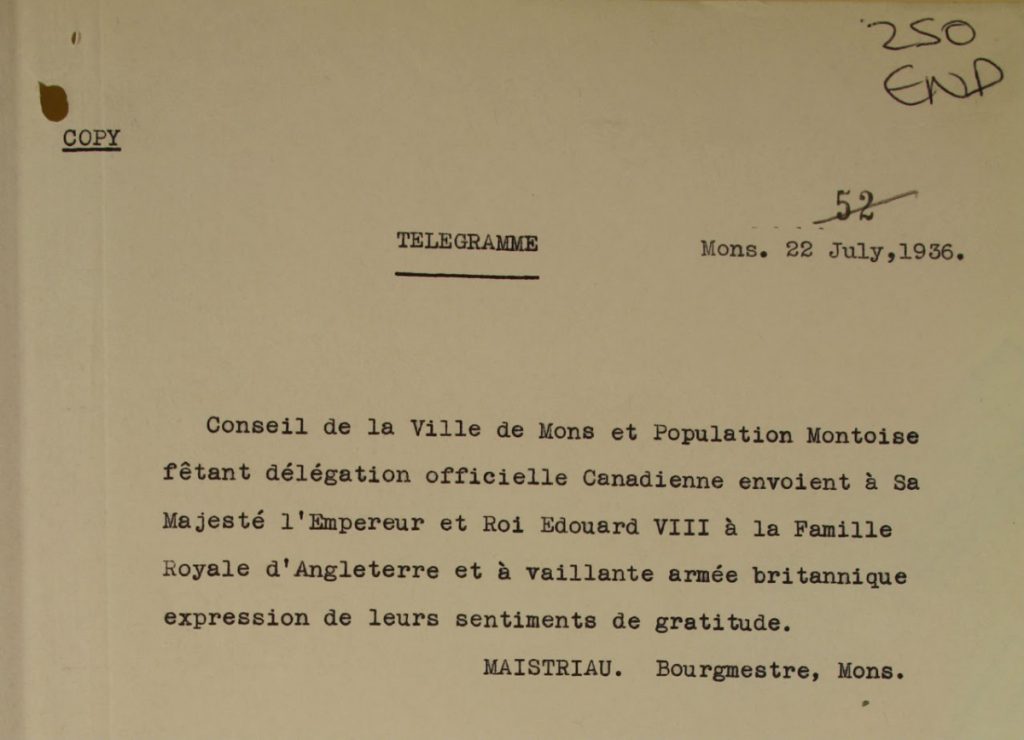

- Telegram regarding Canadians visiting for the Vimy dedication, July 28, 1936. (The National Archives, FO 371/19877)

Paul Piroson continued working at Vimy after the war. When he retired in 1965, Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson personally invited the Pirosons to make their first visit to Canada. They toured the country in 1967, being honoured at a series of events that marked the battle’s fiftieth anniversary.

The men who fought at Vimy Ridge believed it was the moment when they became Canadian and in which the nation was born. The idea grew over the years, and today the battle symbolizes Canadian service and sacrifice in all wars. The name “Vimy” is invoked in many military commemorative projects, while thousands of people from Canada and elsewhere visit the memorial each year to learn what Canadians achieved there in 1917.

- Lieutenant-General H.D.G. Crerar and Paul Piroson at the Vimy Memorial, September 11, 1944. (Library and Archives Canada, MIKAN 4233251)

- View of Vimy Memorial, undated. (Library and Archives Canada, MIKAN 4234839)

This blog was developed under a collaborative agreement between Library and Archives Canada and The National Archives. It was written by Andrew Horrall, who is an archivist at Library and Archives Canada in charge of military records and an historian of English music hall. He holds a Phd in History from the University of Cambridge.

Look out for the last blog in the series on 26 April.

My Great Uncle Ernest William Stanbridge was a Sergeant in the 21st Battalion CEF and was awarded the Military Medal during WW1.He was amongst the returning Canadian Legion veterans on Canadian Pacific SS Montcalm from Montréal, Québec, Canada which arrived at London Tilbury Dock 29th July 1936 on route to Vimy Ridge .He stopped off in England on the way back to visit his sisters and his brother (my Grandfather) before departing back to Canada from Liverpool aboard Canadian Pacific SS Montclare on 7th August 1936. I have photos of him with colleges on Montcalm and at Vimy Ridge wearing his beret, also him getting his MM from Princess Mary of Teck.