In a 1955 Pathé clip on YouTube about the relationship between the growing West Indian community in Lambeth and their white neighbours, the narrator emphatically declares that the colour bar is ‘officially unrecognised’ in Britain. Yet in the collection at The National Archives, we see that multiple regulatory bodies enforced rules which discriminated against people on the basis of colour throughout the 20th century.

Most of the references within this blog are found in CO 876/89. Other examples of the colour bar in hotels, bars and restaurants (HO 45/24748), as well as the services (DEFE 7/1040), are present elsewhere in the archive. In trying to understand the far reaches of discrimination in Britain, this blog takes a closer look at sport and particularly boxing as a cultural arena for debates around race and citizenship.

Cancelled: Jack Johnson vs Billy Wells

One of the early visual records we have of boxing at The National Archives is a photograph taken by Warwick Brookes in 1911. The image shows a group of nine men posed formally with Jack Johnson, aka the Galveston Giant. Johnson was a Texas-born fighter, former dock worker and son of former-enslaved people, who held the title for the World Heavyweight from 1908–1915 – the first Black American to do so.

Johnson’s trip to Britain in 1911, at the height of his fame, was followed closely by the transatlantic press, at a time where networks of mass consumer culture were expanding rapidly. He was a contentious figure in the sport, beating white challengers in the ring and marrying white women. Johnson was also abusive and on one occasion hospitalised his first wife Etta Terry Duryea.[ref]Theresa Runstedtler, Jack Johnson, Rebel Sojourner (University of California Press, 2013).[/ref]

In 1920, Johnson would serve a year in prison after being convicted under the Mann Act, a federal law that was intended to prevent human trafficking but in practice was often used to punish those in interracial relationships. However it was Johnson’s victory over the American heavyweight champion and favourite, James J Jefferies, in 1910 that triggered racial unrest and lynchings across the US.

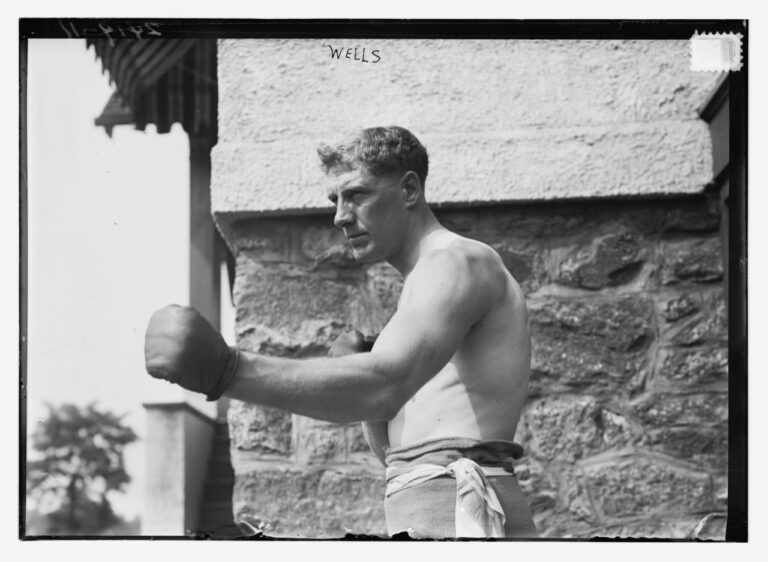

In September 1911 Johnson was set to take on the British titleholder, ‘Bombardier’ Billy Wells, a former soldier in the British Indian Army. Wells was styled as ‘the White Hope’ candidate who would assert the racial hierarchy in a display of masculine prowess. Boxing promoters capitalised on this idea, maximising profits through hosting fights between Black and white athletes. In reality, most ‘White Hope’ fighters were working-class men of immigrant backgrounds. As Theresa Runstedtler argues, these claims to a purely Anglo-Saxon heritage were questionable.[ref]Theresa Runstedtler, “White Anglo-Saxon Hopes and Black Americans’ Atlantic Dreams: Jack Johnson and the British Boxing Colour Bar”, Journal of World History 21, no. 4 (2010): 657-689[/ref] The fight would test white colonial supremacy within the boxing ring in an epic, transatlantic event.

But the fight never happened. Amidst a mixture of protest, spearheaded from the Archbishop of Canterbury and involving Winston Churchill, the Home Office cancelled the fight, citing breach of the peace. Johnson and Wells, their managers, and the promoter were all requested to defend themselves at Bow Street Police Court, culminating in a sensation in the British Press.

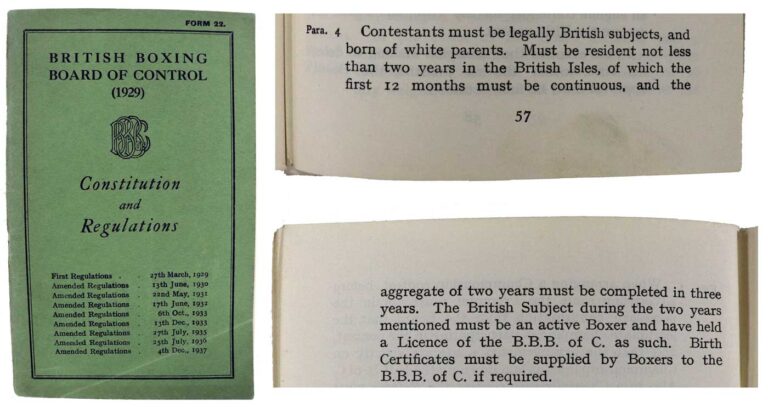

We might assume that boxing promoters at the time were very disappointed by this decision taken by the British government. After all, the sport represented a multi-million-dollar business with worldwide reach, and a new precedent had just been set. The Johnson-Wells controversy was so impactful that the National Sporting Club introduced guidelines banning Black boxers from the British national championship title, an informal but effective rule that was in operation throughout the First and Second World Wars.[ref]G. Brown and S. Hirsch, “Breaking the ‘colour bar’: Len Johnson, Manchester and anti-racism,” Race & Class 64, no. 3 (2023): 36–58.[/ref] The British Boxing Board of Control (BBBoC) took over regulation of the sport in 1929 and seamlessly integrated ‘Rule 24’, which barred those who did not have two white parents from competing for the national title.

Campaigns and controversy

During the interwar years talented Black boxers, some of whom had served in the British forces, were unable to compete for the national title.

In one letter addressed to the Colonial Secretary, former staff sergeant C Harry Daines wrote about Len Johnson, a sportsman with Sierra Leonian heritage who had grown up in Manchester and became ‘one of the most accomplished boxers ever to grace a British ring.’ Len Johnson was one of the most talented British boxers of the interwar period and spoke out about the colour bar in British boxing. His friendship with the singer and actor, Paul Robeson, led to him fighting discrimination outside of the ring and he became an activist in Manchester. In 1953, Johnson led a successful campaign to overturn the colour bar in Moss Side pubs.[ref]For more on Johnson, see Brown and Hirsch, “Breaking the ‘colour bar’: Len Johnson, Manchester and anti-racism”.[/ref]

Although criticism of the colour bar increased during the Second World War, leading to meetings between the Colonial Office and the BBBoC in 1946, the secretary Charles Donmall remained steadfast in upholding ‘Rule 24’:

‘After a somewhat rambling discussion, the Secretary agreed that the Board’s policy was, in fact, a colour bar one, and he tried to defend it on the grounds that the Dominion of South Africa and other Dominions were against coloured contestants fighting for British titles.’

Note by Ivor Cummings, dated 26 June 1946. Catalogue reference: CO 876/89

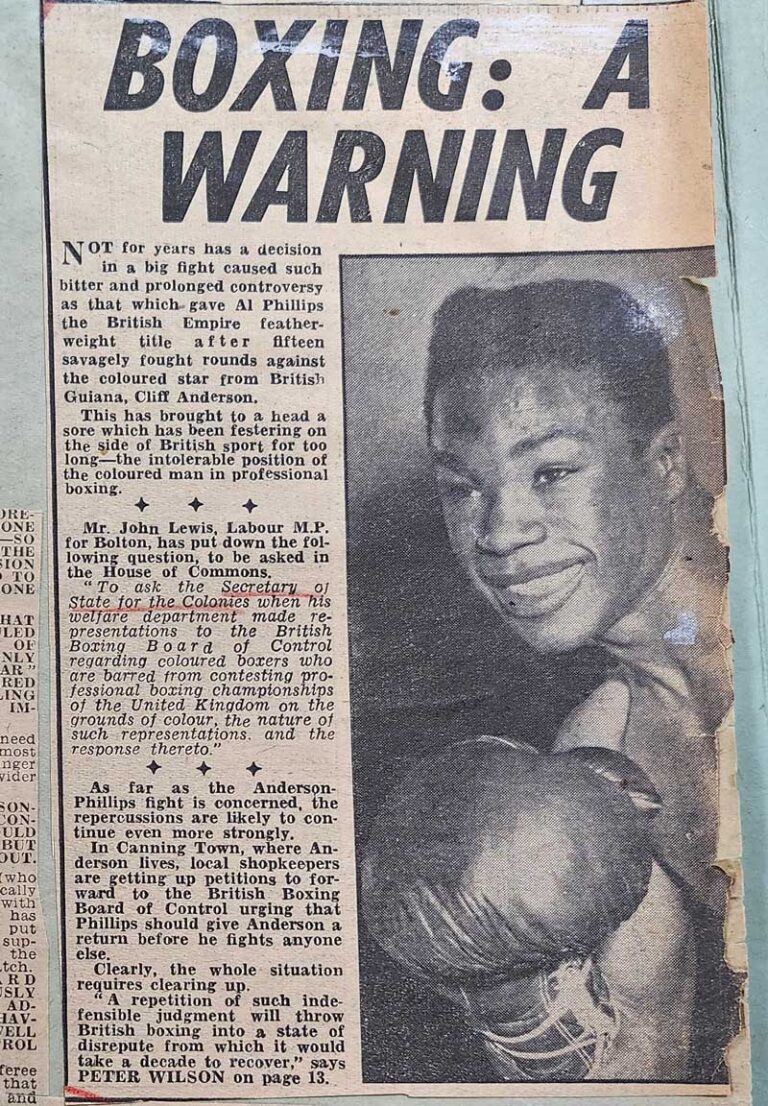

In 1947, press attention in ‘Rule 24’ increased exponentially when Cliff Anderson, a Guyana-born featherweight also known as the Black Panther, lost on a referee decision, which very nearly caused a riot and worldwide controversy. The fight, which was between Anderson and ‘Aldgate Tiger’ Al Phillips, took place at the Olympia in Kensington, London on 18 March. Although Anderson knocked Phillips down four times, the fight was awarded to Phillips. Boxing fans from across the world protested the decision and the issue was even debated in Parliament a few days following.

Little hope was held out that the Board would be prepared to change its policy of excluding coloured boxers from contests for British titles. I regard this colour bar as quite unjustified and I know that it is strongly resented by Colonial people as well as by a large public in this country who are interested in boxing. I hope that the Board may be persuaded to alter their practice.

Mr Creech-Jones, British Boxing Titles (Colour Bar), debated 26 March 1947

In response to the public outcry over the decision, Boxing News raised funds for a special presentation to Phillips in the form of a silver belt awarded to him by Vivian Brodsky, a director of the publication, on 30 June at Ketner’s Restaurant. Anderson and Phillips did meet again in July for a rematch (which you can watch here on British Pathé’s website). However, the match ended again in controversy – Anderson was disqualified when Phillips claimed that his opponent had intentionally punched him in the kidney.

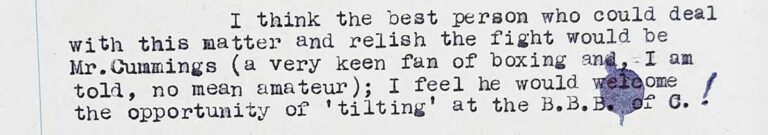

With the galvanising of public opinion, the campaign to change ‘Rule 24’ resumed once again with the help of Ivor Cummings, an advocate for Black Britons who was of Sierra-Leonian heritage, who had been involved in negotiations that had come to a halt in 1946.

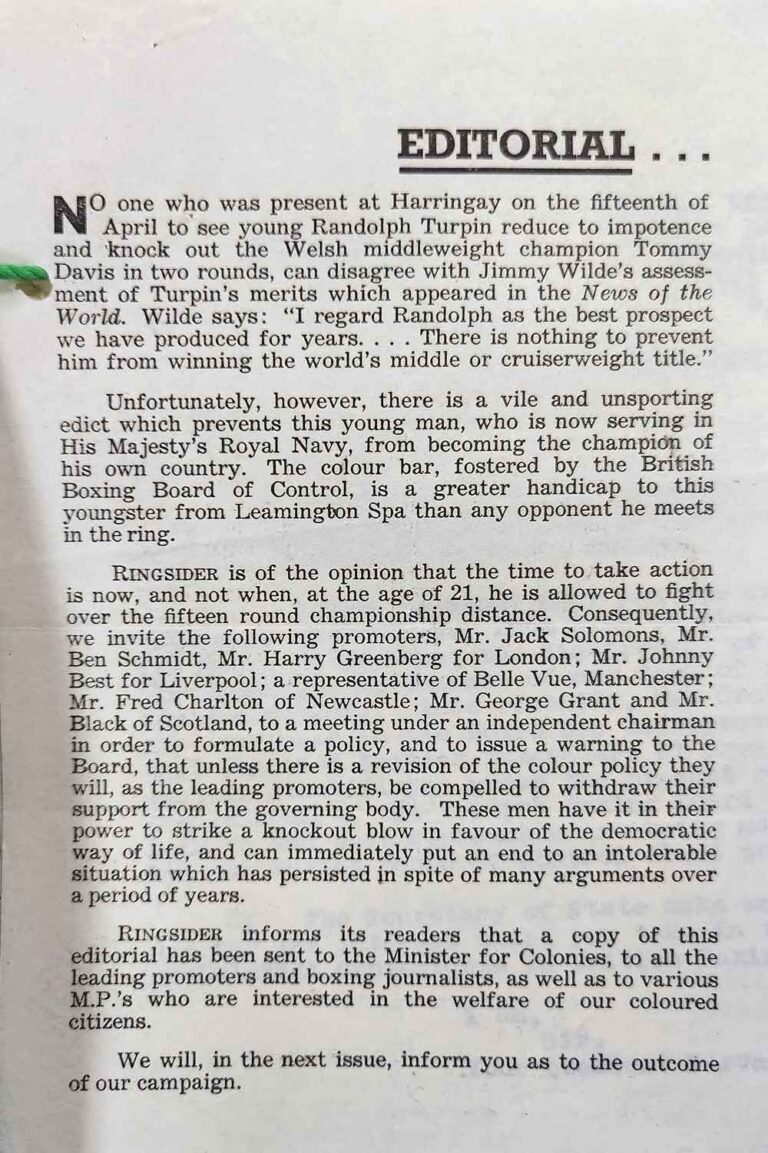

The sporting press also led several campaigns calling for the BBBoC to abandon the regulation regarding participants having two white parents. The Sunday Pictorial ran a poll in May 1947, receiving 19,617 votes in favour of scrapping the colour bar, with just 247 readers against its removal.[ref]Sunday Pictorial, 18 May 1947. Catalogue reference: CO 876/89.[/ref] The boxing magazine Ringsider also threw their support behind Leamington-Spa born Randolph Turpin, who at the age of 21 showed extreme promise in the ring. As part of their campaign, they invited the biggest promoters to formulate a policy and issue a warning to the BBBoC: ‘Unfortunately, however, there is a vile and unsporting edict which prevents this young man, who is now serving in His Majesty’s Royal Navy, from becoming the champion in his own country’.[ref]Editorial produced by Ringsider and sent to the Colonial Office, 3 May 1947. Catalogue reference: CO 876/89.[/ref]

The end of the colour bar clause

In 1947, after continued pressure from the press and the public, and the efforts of Ivor Cummings, Arthur Creech-Jones, John Lewis and others, the British Boxing Board of Control changed ‘Rule 24’ and abandoned the colour bar clause. The new rule officially came into operation in 1948.

Dick Turpin – the brother of Randolph Turpin – won the middleweight championship, a national title, the very same year. Turpin was the son of a white British woman and a Black man from Guyana, who had stowed away on a ship bound for England to fight in the First World War. His brother Randolph Turpin, who also experienced an extremely successful boxing career, is the more well-known of the two.

Despite this great achievement, it was unclear to what degree leaders of the BBBoC recognised the regulation as a formal colour bar, emphasising that the national championship remained, ‘open to those who by birth and residence have a stake in the country and look upon it as their home’.[ref]Field Roscoe & Co. solicitors to Secretary of State for the Colonies, 28 July 1947. Catalogue reference: CO 876/89.[/ref] Despite the passing of the British Nationality Act in 1948, which created a uniform legal status for all British subjects, the amended ‘Rule 24’ continued to stipulate that for the national title, competitors had to be born in Britain.[ref]M. Johnes and M. Taylor, “Boxing, Race and British Identity, 1942-1962″, The Historical Journal, 63, no. 5 (2020):1347-1377.[/ref] Thus, competitors arriving in the post-war period from the Caribbean had to take on the Empire title before domestic titles, making progression in the sport extremely difficult.[ref]Black boxers also travelled on the iconic Empire Windrush. London: MV Empire Windrush (The New Zealand Shipping Company Ltd) travelling from Kingston to London. Catalogue reference: BT 26/1237/91.[/ref]

The fight between Jack Johnson and Billy Wells may not have happened, but its impact on British boxing reveals a time when the formal colour bar was not yet in existence. Only a few years before the proposed Johnson-Wells encounter, Andrew Jeptha won the domestic welterweight title in March 1907. Born in South Africa, Jeptha is considered one of the forgotten stars of British sporting history.[ref]According to Gary Shaw. See this article from The Liverpool Echo.[/ref]

The success of Jeptha, and later, Len Johnson, offers an image of British identity which is not based on whiteness and stands apart from immigration in the late 20th century. [ref]See also our resource on Black boxers in the early 20th century.[/ref]. It is also important to note that Len Johnson and the Turpin brothers were mixed race, although they would have been racialised as Black at the time.

More importantly, the accession of colour bar regulations by bodies such as the National Sporting Club, and later the British Boxing Board of Control, demonstrates that competitive sports like boxing became part of wider cultural reconfigurations of race. Through the lens of sport, we can begin to see the shifting of the global order in the 20th century, and in the boxing ring, the embodied fears and hopes of the fragile imperial body were realised on a truly epic stage.