Whilst going through some papers of the British Delegation at the Paris Peace Conference, which took place at the end of the First World War, I came across a rather unusual memorandum by the highly controversial figure of Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen, who was serving as a military advisor to the British delegation. Meinertzhagen suggested a solution to the thorny issue of what to do with the German island of Heligoland: turn it into a bird sanctuary.

Heligoland was one of the most important naval issues up for discussion at the Paris Peace Conference. The island, located 30 miles off the German coast, had posed a serious threat to the British control of the North Sea during the war. It was highly fortified and acted as a base for German submarines, torpedo boats and aircraft attacking British shipping. The British were very keen for all of the fortifications on the island to be removed but there was less certainty about what to do with the island itself. The Admiralty in London wrote to the Prime Minister: ‘It is most undesirable, from a practical point of view, that Great Britain should take possession of Heligoland; it is undesirable, from a point of view of sentiment, that Germany should retain ownership’ (FO 608/132/6 , file 465/5/1).

Richard Meinertzhagen, image from Wikimedia Commons http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:RMKenya1915.png

It was here that Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen entered the discussion. Meinertzhagen is a fascinating character. He had joined the army prior to the war and worked with T E Lawrence in Arabia in 1917. Lawrence wrote of Meinertzhagen that he was:

‘a student of migrating birds drifted into soldiering, whose hot immoral hatred of the enemy expressed itself as readily in trickery as in violence… Meinertzhagen knew no half measures. He was logical, an idealist of the deepest, and so possessed by his convictions that he was willing to harness evil to the chariot of good. He was a strategist, a geographer, and a silent laughing masterful man; who took as blithe a pleasure in deceiving his enemy (or his friend) by some unscrupulous jest, as in spattering the brains of a cornered mob of Germans one by one with his African knob-kerri. His instincts were abetted by an immensely powerful body and a savage brain, which chose the best way to its purpose, unhampered by doubt or habit.’ [ref] 1. T E Lawrence, Seven Pillars of Wisdom, (London: Wordsworth Editions 1997) Pg. 376 [/ref]

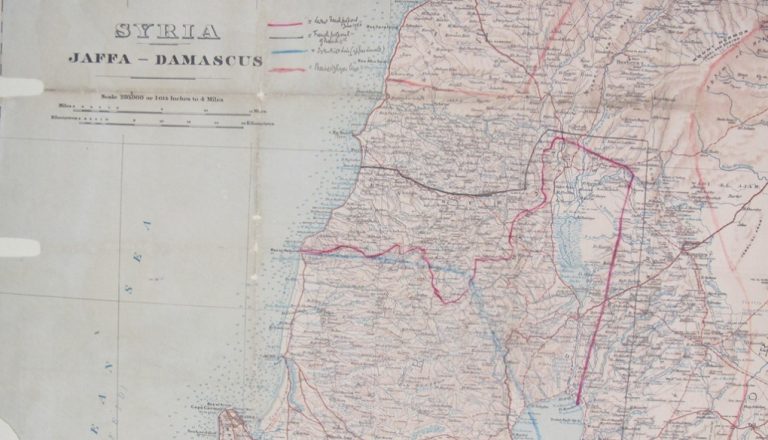

Meinertzhagen continued in the British Army after the war, serving at the Paris Peace Conference and helping to draw up the boundaries of the British and French spheres of influence in the Middle East. One such boundary was even called the Meinertzhagen Line. Following his army career Meinertzhagen went on to be a globally respected ornithologist, working with the Natural History Museum.

This reputation has been heavily tarnished since his death by the revelation that he falsified a number of the new species he was supposed to have discovered, and conducted other unscrupulous practices. A recent biographer has even gone so far as to suggest Meinertzhagen may have murdered his wife, who died in what was then considered a shooting accident in the 1920s. [ref] 2. Brian Garfield, The Meinertzhagen Mystery, (Washington D.C.: Potomac Books, 2007) [/ref]

Meinertzhagen’s fascination with birds is, however, undeniable and it was this that motivated his idea for Heligoland. He began his proposal with the caveat that ‘this Minute is not an expression of opinion from the Military Delegation, but from one who has devoted thirty years to the study of birds in all parts of the world and whose love of birds surpasses that for his fellow creatures’. Meinertzhagen went on to outline how the island was, in the migratory season, ‘a veritable aviary, when bird life from two continents passes on its journey from summer to winter haunts and back again in spring’.

This extraordinary man was horrified that the Heligolanders used this ‘most wonderful phenomenon’ as ‘the excuse for wholesale slaughter by every means’. Worst of all, these birds were killed ‘not for sport but purely for the pot… The world is annually made less beautiful and less pleasant by the actions of the Heligolanders’. Thus Meinhertzhagen suggested that the island be turned into an international sanctuary and a de-militarised zone, helping to ensure peace for bird and man alike. As surety for these ideals Meinhertzhagen argued that a British agent should be resident on the island, as ‘an Englishman’s love of nature and his hated of injustice and cruelty to wild animals, fits him more for such a post than do the qualifications of either Teuton or Latin Races’ (FO 608/132/6 , file 465/5/1).

The British delegation at the Peace Conference certainly took Meinhertzhagen’s suggestion seriously. One clerk minuted ‘if we do not want Heligoland ourselves nor wish it to remain German, the idea of a Bird Sanctuary – (duly neutralised and internationalised) – might perhaps find acceptance with the Conference’. The leading Foreign Office figure, Eyre Crowe, was rather more sceptical and ‘found it difficult to take this suggestion seriously’ but passed it on to his political masters nonetheless. The issue was discussed at the Council of Four, the highest level of the Conference usually made up of President Woodrow Wilson, representing the United States, the British Prime Minster, David Lloyd George, the French Prime Minister, Georges Clemenceau, and the Italian Prime Minister, Vittorio Orlando. The question of Heligoland was discussed by the Council on 15 April 1919; however the sparse minutes give no indication of how the proposal to turn the island into a bird sanctuary was viewed. They merely record that provisions for destroying the fortifications and the harbour should be included in the treaty (FO 374/30). Despite further interest in Meinhertzhagen’s idea from figures in the Natural History Museum and the Royal Society, and the support of Arthur Balfour, the Foreign Secretary, it was not raised again at the Council of Four.

Like much of the Treaty of Versailles the suggestion to turn Heligoland into a bird sanctuary can be seen as a missed opportunity. The island was rapidly re-militarised by the German government in the 1930s and served as an advanced base for submarines and aircraft throughout the Second World War. On 18 April 1945 the island was devastated by an RAF bombing raid, and continued to be used as a bomb target after the war. In 1947 it was the location of one of the largest non-nuclear explosions and it was not until 1952 that it was returned to the German Government. Gradually it has regained its position as a staging post for migratory birds. Although it came many years after Meinhertzhagen’s initial proposal, the birds of peace have now replaced the birds of war on Heligoland.

Dr Dunley

Very interesting original map of the border proposals. Have you seen other maps in the British Delegation Papers to the Peace Conference i.e. Lebanese or Zionist?

Bassam Namani

Ambassador of Lebanon to Tunisia