In 1914 a very concerned father sent a letter to the school teaching his young child. The complaint? He was concerned that ‘sexual instruction’ had been given to his 11-year-old daughter by Miss Outram, Headmistress of the Girls Department at Dronfield School, near Sheffield. The teacher was taking a radical approach to sex education and teaching the girls herself. A file documenting this entire episode is held in the Board of Education records at The National Archives and makes for a fascinating read[ref]Health and sex education. Agitation in Dronfield, near Sheffield, over sex talks given by Headmistress of Dronfield Council School to girls aged 11 years. Reference: ED 50/185. Most of the content of this blog comes from this file.[/ref].

‘These 1914 pp. [pages] should be preserved. To the historian they will throw much light on the narrow outlook, in those days’

Note on front of file, c. 1943, ED 50/185

The lesson complained about was meant to be one on scripture. But as the class progressed, Miss Outram was asked a series of inquisitive questions by her girls. At first, she told them to ask their mother: ‘she is the proper person to tell you’.

In response the Headmistress read them two short stories, which are included in full in the file. Both were heavily allegorical, and far from controversial from a 21st century perspective. The first used religious ideas and seeds to discuss the ideas of childbirth;

‘a little seed is sown in the inside of your mother’s body. God opened a door to you and brought you out into the world.’

The second story focused more on chastity and self-control, suggesting relationships and sex were not things to be rushed into lightly. The tale uses electricity as a metaphor for sexual urges and desire.

Neither story explicitly mentioned sex or sexual acts, however in the context of the Edwardian period this was very controversial. At the turn of the century, various social movements supported sexual purity, hygiene and feminism; all of which pushed for more sex education for various different, often intersecting, reasons. In this era the conversation around sexual education often also linked into conversations around eugenics and limiting population size.

Ultimately, there was no formal or standardised sex education in schools at this time[ref]Dr Lynda Measor, Katrina Miller, Coralie Tiffin, Young People’s Views on Sex Education: Education, Attitudes and Behaviour, p. 17.[/ref]. Just talking about sex and relationships, even in these vague terms, was feared to have the potential to corrupt the young girls’ minds.

Controversy spreads

The children went home and mentioned it to their families and the message spread. The sexual instruction in question was claimed to be various things, indeed some parents even refused to speak of it when asked, so sensational was it thought to be. There appears to have been very little knowledge of what was actually said. One father noted:

‘Mrs Penn I shall not let our Betty come while Miss Outram is in the school. She has not told me what she [Miss Outram] has said, but I shall not let her come.’

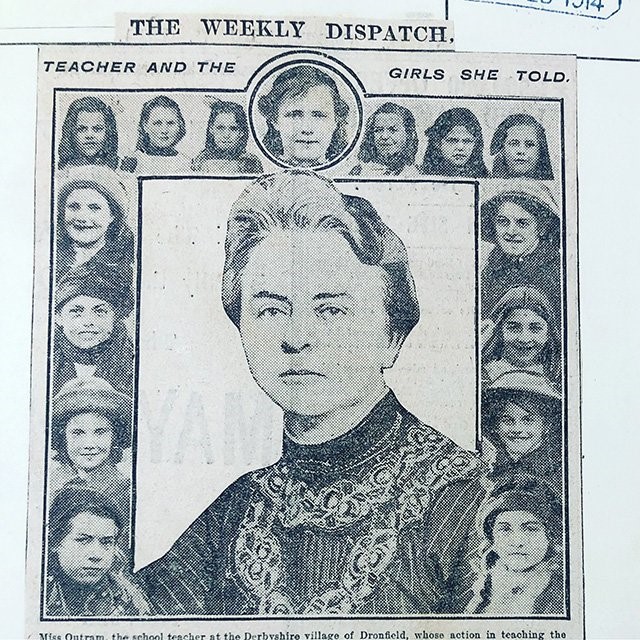

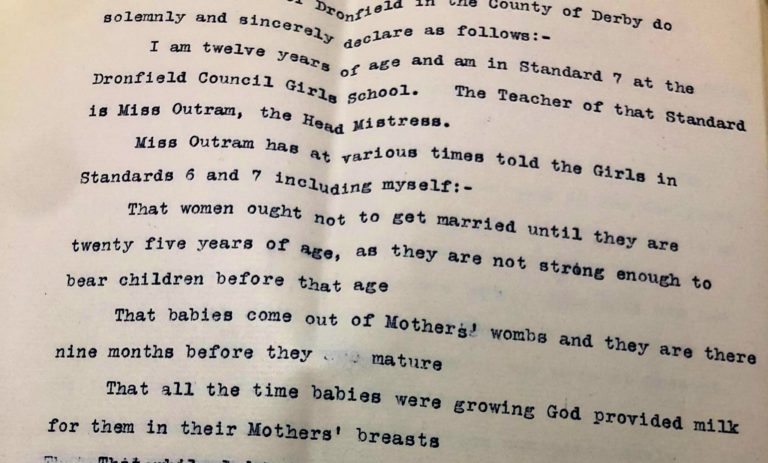

Multiple testimonies from the 11, 12 and 13 year olds were recorded and describe some of what they were told. One 12-year-old girl mentioned various things that Miss Outram had recounted previously, including telling the girls about breast-feeding and that ‘babies come out of mothers’ wombs and they are there nine months before they mature’. Another claimed the outline of a man had been drawn on the board (shocking!). The testimonies seem conflicting and the version of events that spread among parents seemed equally unclear.

Miss Outram was not helped by previous criticisms that had been made against her. In February 1911 there had been complaints about her teaching suffragette doctrine. At the time she reassured managers she would not teach controversial subjects in the future.

School strike

Ultimately parents were so distraught about the sex education received by their girls that only 11 of Miss Outram’s 36 pupils attended school. Effectively, parents were instigating a school strike.

This was followed by a mass meeting of concerned parents and local residents, and a resolution was passed for Miss Outram to resign. A petition was signed by 1,220 inhabitants of Dronfield – a very significant number given the small local population. As Hera Cook noted, many of the girl’s parents would have been born in the 1860s or 1870s according to census records, and this case in Dronfield reflects the attitudes and values of the Edwardian period. It also says a lot about sex education in the time their parents were raised[ref]Hera Cook, ‘Emotion, bodies, sexuality, and sex education in Edwardian England.’ The Historical Journal 55, no. 2 (2012). P. 476. Accessed June 9, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/23263346[/ref].

However, it is worth noting that Miss Outram also received many letters of support, one from the progressive local campaigner and free love advocate, Edward Carpenter[ref]https://www.sheffieldtelegraph.co.uk/retro/story-lady-who-dared-makes-fascinating-history-project-468787#gsc.tab=0[/ref].

Miss Outram made this statement in January 1914 at a School Managers’ meeting:

‘I acknowledge it is a mistake. I will be more careful in future. It is a lovely little story all the same and there is no harm in it. We all make mistakes. I was not wilfully doing anything wrong, if I have done anything wrong. I do not acknowledge that I have done anything wrong.’

Ultimately, two things intervened in Miss Outram’s favour: the tensions between the local and county Education boards (the Derby County Education Board was not keen to intervene) and, ultimately, the First World War. It appears that on the outbreak of war the Board of Education closed the file, seemingly with no final resolution to the conflict, as more pressing matters had taken precedent[ref]Frank Mort, Dangerous Sexualities: Medico-Moral Politics in England Since 1830.[/ref].

Feminist politics

But what of Miss Outram and her radical politics?

No doubt the parents would have been shocked to find out about Miss Outram’s wider political beliefs. In 1918 she was not only present at, but chaired, a meeting of 300 teachers and women students in the Cutlers’ Hall to talk about equal pay for equal work in the teaching profession[ref]Britannia, Official organ of the Women’s Party, Apr 1918, The British Library.[/ref]. The meeting was organised by the Women’s Party (which had developed out of the Suffragette organisation the Women’s Social and Political Union, or WSPU) and the key speaker was the Suffragette leader Emmeline Pankhurst herself. This was just four years after the sex education controversy.

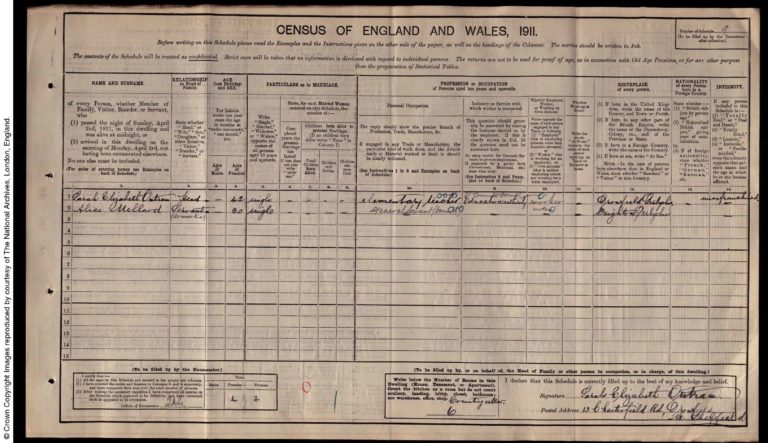

Many teachers were part of the women’s suffrage movement. Miss Outram’s census schedule tells us a little more, including that she wasn’t one of the suffrage supporters to boycott the census[ref]Sarah Elizabeth Outram, Dronfield, Derbyshire, 1911 census. Catalogue ref: RG 14/21166.[/ref]. However, it is also clear that before this time she donated to the WSPU, the militant fraction of the women’s suffrage movement.

‘What shall I tell my child?’

The reaction to Miss Outram’s allegorical stories is an example of how controversial sex education was for young girls at this time. It shows a fear of female empowerment, and illustrates the slowly changing world that the girls would be growing up in.

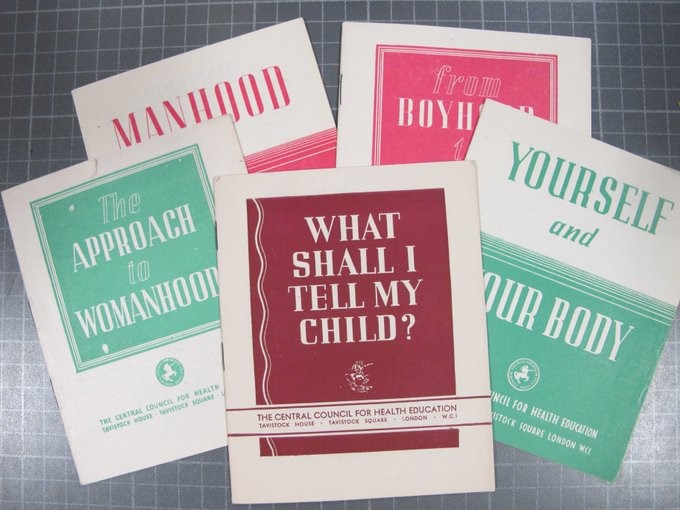

Just 30 years after this scandal, a lot had changed. A pamphlet series entitled ‘Sex Education in Schools’ was produced for distribution between 1942 and 1954. The state was slowly becoming more involved in introducing sex education to schools for both girls and boys.

I found this Blog very interesting. I was a nurse and worked for the Family Planning association in the 60’s. Women paid 2 guineas a year to attend clinics for contraceptive advice.They had to be married or engaged. When the FPA announced that ALL women should be seen in the clinics all our volunteer helpers walked out en masse, as they thought this very immoral! Eventually, as was the aim of the FPA, contraceptive advice was free for everyone and became part of the NHS.

In the late 70’s I visited several secondary schools to gave talks on Contraception to boys and girls during their final year.Before I started doing this one of the schools decided to show the film on contraception to the parents at the AGM of the PTA,so they knew what their children were going to be told. The uptake was huge, the school hall was packed for the first time ever at an AGM. The parents agreed for the talks to go ahead.

I was once asked by a teacher to talk to year 6 (10 – 11 year olds) children on the human body , she stipulated that I shouldn’t mention sex organs!! Of course the children asked me about them, so I managed to include them. What was the teacher worried about?

Learning about sex should be a natural process in a child’s life. All questions from them should be answered honestly and openly. Then they won’t grow up in ignorance of what is just part of life.

I was a nurse in the 1960s and doing my midwifery exams by 1964. A fellow midwife told me that she had been asked by a young wife in labour when she was going to use the razor she had been asked to bring along.

In 60s in Britain’s NHS , when mothers- to- be were to be admitted for the birth , they were advised to bring in with them – a comprehensive layette for the newborn , a change of nightwear for themselves and extras like soap, flannel and a roll of SOFT toilet paper. ( NHS issue paper was Izal – rather harsh scratchy paper,) and a new safety razor blade . (It was routine that the pubic area was shaved to avoid any transition of infection) The NHS issued razor blade was expected to last 10 patients so if you were no 10… could be painful- hence the request.

This young girl was raised on a isolated farm helping her family til she married. she assisted with all the farm jobs including animal husbandry but had attended few ante-natal classes. for herself

When the midwife told her she was going to use the blade to shave her “down-below” she was shocked when the young woman refused – she expected the sharp blade to be used to cut open her abdomen and she wasn’t going to be different to anybody else. A lot of gentle tact and education was given in the few hours left before labour begun in earnest. But the ignorance was shocking to the midwife and her colleagues but it still persists in communities today.

And a distinct lack of sex education led to my having an illegitimate child in 1963 — and being ostracised for refusing to let her go for adoption (but that;s a different story).