As one of the selected Decade of Centenaries Artists in Residence, I am extremely fortunate to have the opportunity to work alongside the Beyond 2022 multi-disciplinary team as they undertake the mammoth task of producing a virtual reconstruction of the Record Treasury of Ireland, destroyed in the fire at the Four Courts complex in Dublin at the start of the Irish Civil War.

‘There is a crack in everything, that’s how the light gets in’

Leonard Cohen

Due to COVID-19, my introduction to the team came through online weekly meetings. The task seemed enormous. I imagined this vast, archival recovery project akin to a broken ceramic bowl in the process of being repaired using the Japanese method of Kintsugi. Kintsugi philosophers believe that nothing is ever truly broken. Repairs can be made to an object using glue containing gold leaf, making the original object even stronger and more valuable. When the pieces are bonded back together, the vessel can continue to fulfil its original purpose, moving on unencumbered by its close encounter with destruction.

Down in the hole

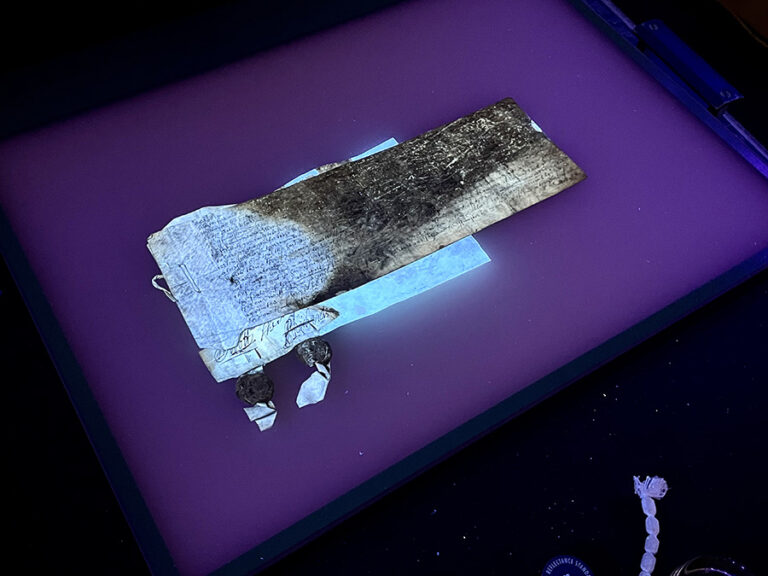

One of the key partners of the project is The National Archives in London. On a visit there, I saw multi-spectral imaging cameras and scanning devices at work looking ‘in and through’ damaged documents similar to those saved from the 1922 fire in Dublin. This made me think about how much we don’t know from looking just at the surface.

The team at The National Archives arranged a visit to their Deep Store in the salt mines in Cheshire, where I filmed the tunnels and passageways of the working mine, as well as the vast storage units set aside for the archives. Accidentally, I left my sound recorder running in that space while filming and photographing in another location. Afterwards, as I listened closely to the resulting recording, I swore I could hear traces of voices in the air. I thought there were vibrations of people coming from their belongings stored in the canvas bags and boxes on the shelves. I imagined they were just waiting until their time would come to be rediscovered. The thought that the lives represented in the archives can only be known if they are made accessible, or visible to the next generation, made me realise what the Beyond 2022 project team is doing. They are making visible the invisible.

Survivors

Amazingly, some badly damaged documents survived the fire. They were gathered from the rubble in 1922 and carefully preserved. I saw photographs of them bundled up in brown paper, tied with string, before I visited the National Archives of Ireland (NAI) in October 2021. These packages reminded me of the film I made in 2004 (Way Past) based on a memory of being sent to pick up repaired shoes belonging to one of our large family of 12 children (that’s 24 growing feet!) in the late 1970s in Taggart’s Shoe Shop in Omagh, Co Tyrone. Standing at the counter, I could see rows of shelves packed with brown paper packages, each labelled with a numbered docket, matching the ticket stubs handed in by the owner when collecting their repaired shoes. The salvaged archival documents wrapped in the same paper as the shoes had no elves to magically repair them, as they had done in my childhood imaginings in Taggart’s shop.

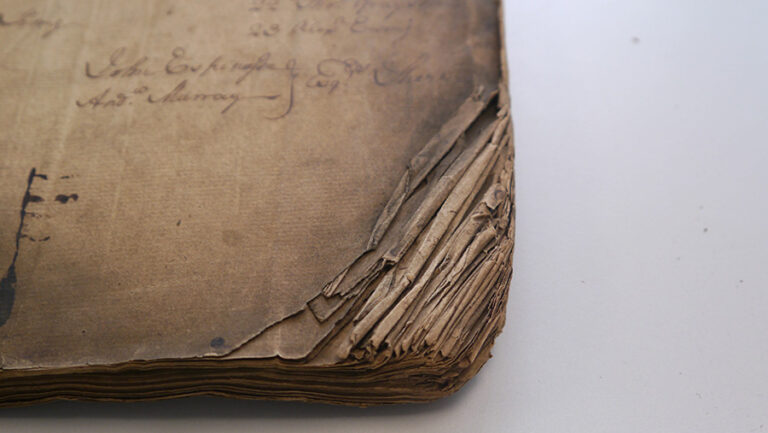

When these documents were eventually opened and moved to clean grey boxes, they looked exactly as they had done when they came out of the fire. I photographed them in their various states of repair; some badly burnt, some scored with blasts of shrapnel, some charred and covered in dust and dirt, some a tangled mess of all of the above. There were labels with detailed descriptions, but other smaller items just had a note and a number saying, for example, ‘Fragment of a Fine’. When looking at the photographs I took that first day, it was these ‘uncoupled’ fragments that drew me in; they had lost their moorings, their owner, their original ticket stub, and had come adrift.

Brittle and burnt

In the weeks that followed I filmed the National Archives of Ireland conservation team as they cleaned and mended torn and damaged documents. One day, I noticed a glass jar standing on a nearby table filled with small dark shards of what appeared to be burnt paper. Upon inquiring what this was, I discovered that these tiny pieces had fallen off the edges of repaired documents. I photographed the jar, side on, without the lid and then from an overhead perspective, thinking later about this as a ‘leitmotif’ for the work I might make. Looking more closely at the fragments, I noticed they consisted of edges chipped off the bindings or corners of documents and manuscripts. To an untrained eye it appeared these fragments were just being collected in the jar to be thrown away. They seemed to offer very little else; nothing was written on them – a faint letter or a word here or there but most were blank. This absence of text, the lack of a narrative, fuelled more questions. Could these fragments provide me with a mechanism to show how the archives could be virtually put back together? Could I use them to reflect on how I ‘cut’ pieces of filmed material in the edit to ‘prick’ memory?

Drawn to the edge

While the Conservator may perceive the edge of books or manuscripts as a ‘weak point’, they are the point of access to historians who touch the page to read the book. The edge is held between the finger and the thumb when the page is being turned. When the reader moves to the next page the weakness of the edge is manifest. The more readers of the page, the weaker the edge becomes. In the handling process, the residue of dirt or oil left over time by the fingers, or the traces of the DNA left by the spit sometimes used to ease the pages apart, causes damage. When a book is archived, the edges can experience wear and tear when they are moved from shelf to viewing table and back. In the explosion and subsequent fire in 1922, it was these outer edges off the manuscripts and books, the front and back covers, which took the biggest hit.

I can hear it

Growing up in the late 1960s/1970s in Northern Ireland, the sound of a bomb blast was not an unfamiliar one. When I lived in London as a student in the 1980s/90s, I found I had the ability to recognise that sound before any of my English counterparts. ‘What was that?’ they’d asked. ‘Sounds like a bomb blast to me’ I’d say. The ‘boom’ seemed to reverberate through the air and although thankfully bombs were not that commonplace in London, somehow my ears had retained the memory of the sound from childhood.

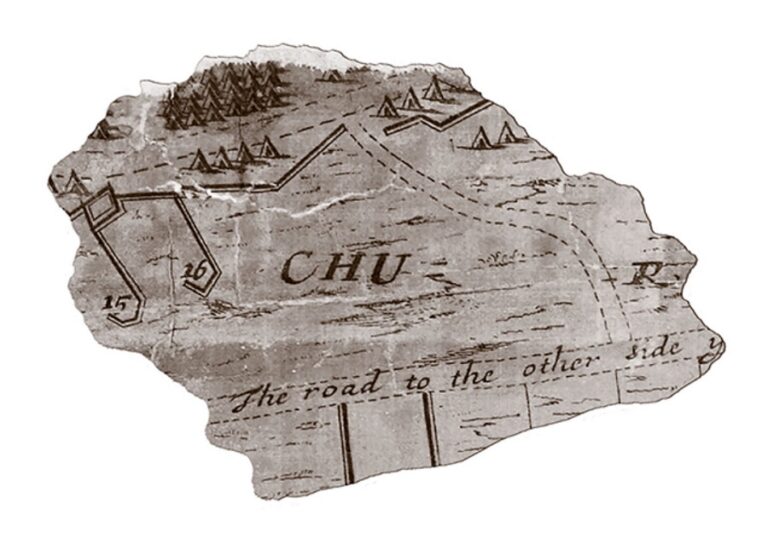

Viewing the film footage of the shelling of the Four Courts in 1922 made me ‘feel’ the sound again, as did the Londonderry Siege Map of 1689. This map, shown to me by the conservation team at The Public Records Office Northern Ireland (another Core Partner in this project), is exquisite in its detail. It depicts the Jacobite encampments (their tents look like teepees) outside the walls of the city and even shows the trajectory of the cannon balls as they fly through the air to the other side of the river Foyle, plumes of smoke drawn to depict the devastation as they landed. As I time-travel virtually through these archival documents, the word ‘reverberation’ floats towards me like a hologram and ‘Reverberation time’ tells me that it is the time taken for a sound to fade away. Another piece of the jigsaw is found.

Turning the page

‘Turning over a new leaf’, ‘turning the page’, ‘flipping the script’ are commonly-used terms to describe starting over or starting anew. The hand holds the pen to write on the page. The pen writes the story of our past. The body becomes the book, the book the body. It says to me: ‘the next page is blank, we can reset ourselves, let’s begin again, we can do better’.

The team involved with rebuilding the Record Treasury of Ireland digitally has been collating vast amounts of archival material from many different sources from around the world into one site, one portal for all to enter. For me this process represents the construction of a bridge between the living and the dead. Like the multi-spectral imaging cameras used in conservation, the new Virtual Treasury allows us to look deep into the well of history to uncover stories that build a bigger and fuller picture of who we are. It allows the reader to now go beyond the original intention of a collected, physical archive. It uses copies, replicas and substitutes which give us not only what the original gave us but more. As in Ridley Scott’s ‘Blade Runner’, replicas (human replicants in the film) have the possibility to be more than the sum of their parts. Data can be examined from multiple viewpoints, analysed statistically to produce knowledge graphs which in turn offer more ways than ever to find ourselves in our past.

My creative response to the reconstruction of the Virtual Record Treasury of Ireland comes out of this extensive period of research. It moves into a longer period of making and producing media artefacts that highlight this incredibly rich resource which is now in all our hands.

This is a fascinating insight into the important work being carried out to recover as much as possible from the damaged records. I particularly liked the comment about hearing voices from the past when the tape recorder was left running – I can imagine the voices striving to tell their story and be heard.

I look forward to seeing the results of this painstaking work as I have a lot of Irish DNA even although I am a Scot.

To Sarah Hendricks

Can I comment on your fascinating article about Irish archives?

John King