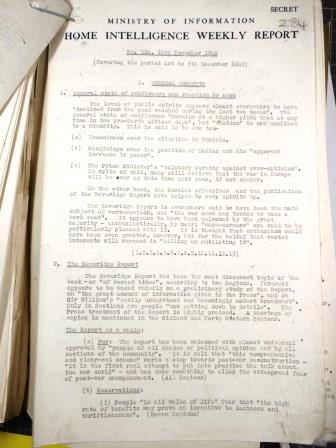

Frontispiece of the Beveridge Report, 1942. Catalogue reference: PREM 4/89/2

‘Now, when the war is abolishing landmarks of every kind, is the opportunity for using experience in a clear field. A revolutionary moment in the world’s history is a time for revolutions, not for patching.’

This was Sir William Beveridge’s clarion call to Parliament to establish a comprehensive system of social insurance for Britain’s population in his report Social Insurance and Allied Services, better known as the Beveridge Report, which was presented to Parliament on 24 November 1942 and has its 75th anniversary this year.

The Five Great Evils

The Beveridge Report, to quote Conservative Chancellor Kingsley Wood, is ‘lengthy’ [ref] 1. Wood’s summary of the Beveridge Report, 17 November 1942. Catalogue reference: PREM 4/89/2 [/ref], a detailed survey of the state of welfare in Britain and its suggested future direction.

At the heart of the report was Beveridge’s decree that future action to improve social insurance, steps on the road of ‘social progress’, should not be hindered by any ‘sectional interests’ – instead government should work to abolish the ‘Five Great Evils’ which plagued society: Want, Disease, Ignorance, Squalor and Idleness.[ref] 2. William Beveridge, Social Insurance and Allied Services, paragraphs 7-8. Catalogue reference: PREM 4/89/2 [/ref].

The Treasury, at the time of the Report‘s writing, characterised these ‘Evils’ as possessing an ‘increasing order of strength and ferocity’ and Beveridge agreed, saying that Want was in some ways the easiest of these giants to attack. Indeed – while his report raised the prospects of education reforms to combat Ignorance, the wave of post-war council housing which would do so much to combat Squalor, and the prospect of a full employment economy doing away with Idleness – the Report set itself out merely as the first step down the road of ‘social progress’ to a society free of these evils.

At the heart of Beveridge’s plan to rid Britain of Want and its companions was a comprehensive system of social insurance and welfare: universal benefits so that families would never ‘lack the means of healthy subsistence’ for lack of work or income. Beveridge tasked the state with establishing a ‘national minimum’, a safety net below which no one could fall. Central to his plan was a contributory system which would entitle the population to maternity, child and unemployment benefits, state pensions and funeral allowances. Underpinning all of this would be a free at the point-of-use universal health care system, to care for the nation’s health regardless of personal circumstances.

Pre-war poverty

People in Britain, of course, faced incredible privations and hardship during the Second World War as Beveridge was writing his report – rationing, air raids, a national contribution to the giant war effort – but Beveridge’s Report was also written to ensure that the dreadful poverty many in Britain experienced in the economically depressed decades between the First and Second World Wars never returned.

Documents within The National Archives give us a sense of the levels of poverty people faced during this period.

In 1936, three years before the war, the Unemployment Assistance Board commissioned the Pilgrim Trust to make an enquiry into the affects of long term unemployment on people. The descriptions of the lives of those living in poverty, found in The National Archives record AST 7/255, are harrowing.

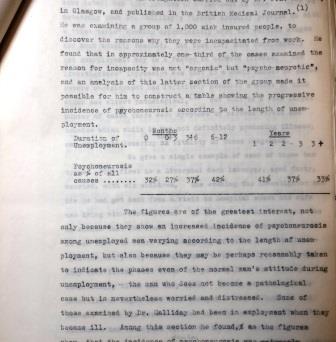

Figures from the The Pilgrim Trust Enquiry into long term unemployment, 1936-1938, examining instances of ‘pyscho-neurosis’ in long term unemployed people. Catalogye reference: AST 7/255

The report, based on interviews with the unemployed in several different towns, gives an insight into the weekly cycle of impoverished life, centred around the day when unemployment assistance is doled out – of one or two proper meals a week followed by only tea and bread, trips back and forth to the pawn shop – a cycle where, ‘there are not a few pennies left over at the end of the week, but a few pennies short’. It includes descriptions of families of four or five people living in one dirty room surrounded by ‘filthy linen and an indescribably horrible smell’. There are details of the physical and mental affects of chronic unemployment – malnourished men and women, men rendered ‘listless’ and depressed by their enforced idleness. It was against this background that Beveridge made his recommendations.

Cabinet worries

Despite the obvious need for an overhaul of social security to prevent such hardship recurring, the transformative scope of Beveridge’s report and the political and economic commitments its adoption would entail still came as a surprise to the Cabinet – particularly Winston Churchill and his closest Conservative ministers, who had misgivings about the feasibility of Beveridge’s proposed schemes.

Churchill received a copy of the report on 11 November 1942, but was no doubt quite busy conducting the war, so instructed the chancellor Kingsley Wood to ‘have an immediate preliminary, brief report made on this for me’. He soon received Wood’s ‘critical observations’, as well as comments from his close friend and adviser Lord Cherwell.

These two reports sum up the initial reception Beveridge’s ideas received from the Prime Minster’s inner circle. Wood described the plan as ‘ambitious’, but worried it involved ‘an impracticable financial commitment’. Wood said that ‘the abolition of want’ was an admirable objective that would have ‘a vast popular appeal’, but he was concerned that Beveridge’s plan was ‘based on fallacious reasoning’.

Wood also raised a number of concerns about the push-back from various industries impacted by the Report‘s recommendations. Would doctors consent to be state employees ? What would the reaction of industrial assurance societies be when the state took their role? How would employers feel about having to make contributions for the unemployed? He was also concerned about the universal, non-means-tested nature of Beveridge’s proposed benefits, drily commenting that:

‘The weekly progress of the millionaire to the post office for his old age pension would have an element of farce for the fact that the pension is provided in large measure by the general taxpayer.’

Wood, as well as Cherwell, also raised concerns about how the United States (who were by and large bankrolling Britain’s war efforts at this point) would react to such bold proposals for state provision by a country brought so financially low by an all-consuming war. Cherwell pointed out that the US population might take umbrage at financing the creation of a far more generous welfare state than their own. Wood worried that it would appear that Britain was ‘engaged in dividing out the spoils while they [the US] are assuming the main burden of the war’.

Concluding, Wood expresses the cautious attitude the Report initially provoked, commenting:

‘Many in this country have persuaded themselves that the cessation of hostilities will mark the opening of a Golden Age: (many were so persuaded last time also). However this may be, the time for declaring a dividend on the profits of the Golden Age is the time when those profits have been realised in fact, not merely in imagination.'[ref] 3. Catalogue reference: PREM 4/89/2 [/ref]

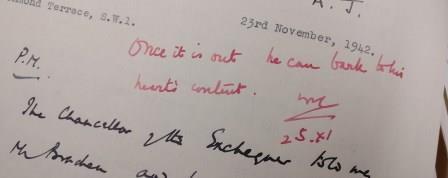

“Once it is out he can bark to his heart’s content” – Winston Churchill’s minute on whether Beveridge should be allowed to speak on his report. Catalogue reference: PREM 4/89/2

As a result of this caution, there was much concern around the publicity the report would receive, and particularly around Beveridge himself speaking on it and promoting its ideas. Even before the report was published there were leaks to the press about its contents, and members of Cabinet worried that Beveridge’s allies were laying the ground work to ensure their friend’s ideas could not be ignored. ‘Beveridge’s friends are playing politics’, the Conservative Minister for Information, Brendan Bracken, wrote to Churchill in October 1942, ‘and when the report arrives there will be an immense ballyhoo about the importance of implementing the recommendations without delay’.

To try and avoid this, Cabinet resolved that Beveridge was to be prohibited from speaking about his Report, or his ideas, before or on the day of its presentation to Parliament, and perhaps after. Beveridge protested, saying he must be allowed to speak on his work. Churchill relented, saying that after the report had been officially published Beveridge could ‘bark to his heart’s content’ about it.[ref] 4. Catalogue reference: PREM 4/89/2 [/ref]

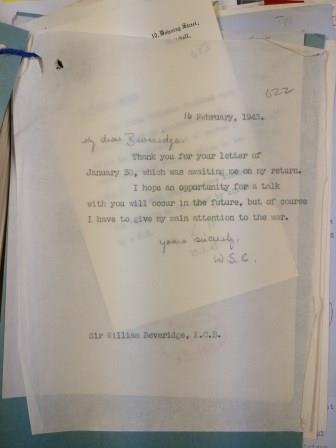

Beveridge’s stock with the government declined with the release of his report. On 30 January 1943 Beveridge wrote to Churchill asking whether he might meet with him, to discuss his future role in government and also social security. Beveridge’s letter is one of effusive praise: he informed the Prime Minister that, while on their recent honeymoon, his wife and he had both read Churchill’s biography of his ancestor the 1st Duke of Marlborough. Beveridge informed Churchill that the book should be ‘compulsory reading for statesmen of all lands … I have noted a least a dozen prognostic passages they ought to learn by heart’.

However, Beveridge had to wait over a fortnight for a reply from Churchill and when it came it expressed the Prime Minister’s coolness to the man whose report had put him in a difficult political position. ‘I hope an opportunity for a talk with you will occur in the future’, Churchill wrote to Beveridge, ‘but of course I have to give my main attention to war’.

Winston Churchill declines Beveridge’s request for a meeting, 16 February 1943. Catalogue reference: PREM 4/89/2

The public’s reaction

But while the Beveridge Report might have been viewed with a sceptical caution by members of government, the views of the British public were another thing entirely, and were decisive in ensuring that so much of Beveridge’s vision for Britain was enacted.

Government public opinion surveys and monitoring from the December 1942 (when the report was made available to the public) onwards show just how favourable the reaction was, and just how sceptical some were that it would ever come to pass.

The British Institute for Public Opinion carried out a country-wide survey on the Report immediately after its general publication. The findings were stark: 95% had heard about the Report and the vast majority of the population approved of its recommendations and thought they should be put in effect, particularly the scheme for a comprehensive state medical service. However, while people though Beveridge’s plan should happen, the poll found few who thought it would happen.

‘The Beveridge Report and the Public’ survey. Catalogue reference: PREM 4/89/2

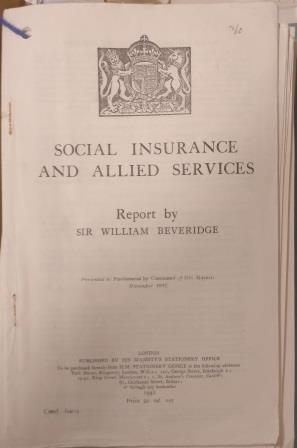

During this period the Ministry of Information produced weekly ‘Home Intelligence Reports’ for government and these also show just how well the Report was received by Britons. In one week in December 1942, for instance, the postal censor examined 947 letters that had been sent about the Beveridge Report, almost all favourable. One writer remarked that the plan would give, ‘the boys who are fighting something to look forward to’, while another remarked that the Report‘s recommendations would bring about a ‘complete social revolution … without bloodshed’.[ref] 5. Catalogue reference: INF 1/292 [/ref]

Ministry of Information Home Intelligence Report, 10 December 1942. Catalogue reference: INF 1/292

Indeed, according to the 10 December report (just days after the Report was made available) Beveridge’s plan was the most talked about topic in the country. A few weeks later people were said to be looking forward to bedding down during the Christmas break to really make a study of it. But this positive reaction seems to have been tinged with scepticism and some anger. The reports note that many people thought that big business would ‘kill’ the report, while another postal censor found a letter predicting ‘serious trouble in this country after the war’ if the report was not adopted.[ref] 6. Catalogue reference: INF 1/292 [/ref]

Legacy

In the face of this reaction the government was pragmatic, reserving its scepticism but making an announcement to Parliament that it would consider the Report and was committed to improving social insurance, but would not make any particular commitments at the present time. Reaction from opposition MPs and the public, again recorded in various public opinion intelligence reports, brought the government back to Parliament again, this time making more explicit declarations of their intent to carry out Beveridge’s plan as far as possible.

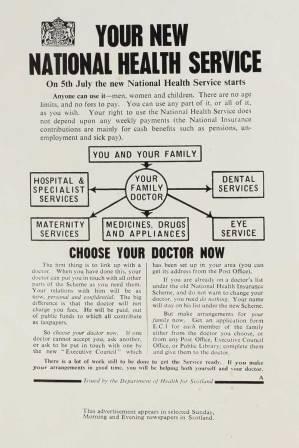

National Health Service Leaflet, 1948. Catalogue reference: INF 2/66

In the end, both the Labour and Conservative parties made adopting a comprehensive system of medical care and social insurance a part of their platform in the 1945 General Election. Clement Attlee’s Labour Party entered government after the election, and continued the work of the wartime government to set up the National Health Service, established in 1948 – perhaps one of the most enduring parts of Beveridge’s realised vision, which itself celebrates its 70th anniversary next year.

The Beveridge Report was conceived in the crucible of war, a bold plan for a nation which had sacrificed so much. Seventy-five years on, we can still see the effects of the ‘bloodless revolution’ it began.

I am somewhat surprised that you have not included any Treasury records in this article. Treasury thought that Beveridge was too expensive leading to their decision that that parents would not be allowed to claim Family Allowance (precursor to Child Benefit) for the first child. The establishment of the NHS was opposed by the Conservative Government and of medical consultants. Beveridge did not eradicate the appalling levels of poverty and squalor in, for example, Glasgow (as shown by the early episodes of “Taggart”) until the early 1970s. As some commentators have recently said Beveridge was built on assumptions in place at the time and that society would not change as much as it has since his day.

David, perhaps you should take the time to read the Beveridge Report before commenting on it.

The Treasury did not decide that Family Allowance would not be paid for the first child, but merely followed Beveridge’s explicit recommendation at Paragraph 417:

“in any system of children’s allowances, the cost of maintaining children should be shared between their parents and the community. This can be done in two ways—either by making an allowance for each child which is less than the cost of maintenance, or by making no allowance for one child in each family and a larger or full allowance for each of the other children. The second way is the better and is adopted here, as making a large reduction in the cost of allowances to the community with no hardship to parents,..”

The establishment of the NHS was not opposed by either the Conservatives or the Consultants, but only by the British Medical Association. Winston Churchill committed to establishing the NHS in his ‘From the Cradle to Grave’ broadcast of 21 March 1943 “We must establish on broad and solid foundations a national health service.” Government set to work and in March 1944 the Minister of Health Henry Willink published the coalition white paper ‘A National Health Service’, which contains the things the public value re the NHS. The BMA heaped abuse on Nye Bevan as they had on Willink, but the consultant’s leader Conservative peer Lord Moran PRCP lunched Bevan round Mayfair’s finest restaurants hence the deal that Bevan, many years later, characterised as stuffing their [the consultants] mouths with gold’.

It is utter nonsense to suggest that work on establishing the NHS did not start until after the 1945 election.

Apart from the nationalisation of hospitals and placing Whitehall appointees on Regional Hospital Boards the National Health Service Act 1946 was closely based on the coalition government’s March 1944 white paper ‘A National Health Service’ (Cmd. 6502).

Hi Bill,

Thanks for your comment. You’re absolutely right, I’ve just phrased that penultimate paragraph badly. I will get it corrected.

It must also be recorded that Dame Florence Horsbugh, Tory MP for Dundee 1931/45 and who was wartime Minister of Health, had already completed much of the work on the scheme which eventually became the NHS.

It was also Churchill who appointed Beveridge, his pre first WW Secretary to undertake a report on social reform.

All three parties committed to create an NHS in 1945 with Lab giving an ambivalent commitment and Con giving the longest and most detailed manifesto commitment of all three parties.

Despite the contest cry that Tories want to privatise the NHS, they have been in charge for 43 out of the 70 year existence of the NHS and it’s still a fully National service with Lab introducing more private involvement than any other Gov.

i would like to add that the Beveridge Report had had very little to do with the creation of the NHS. to paraphrase the actual Report, it said that any sensible government would create a a national health system. in other words, it was an assumption by Beveridge and not a proposal with any concrete sucstance.

I am 83 years of age I would like to say that before and during the Second World War I as one of 6 children suffered abject poverty due to poor housing the wrong diet due to lack of enough to eat. Father way in the army mother doing any work to provide the best that she could for six children. My conclusion is beverage did set the grounds fora better standard of living in Great Britain. That is why most people today enjoy a standard of living second to none especialiy in Heath due to the wonderful N H S.

Since the introduction of the National Health Service in 1948 many countries have visited the UK and looked at the NHS. The relevant point is that none of them have copied it. The truth is that our much vaunted NHS is too costly, badly organised and wrongly funded.

My late father returned from WW2 to his job in the laboratory of a pharmaceutical company. He spent the next 35 years with the same company as a sales rep, sales manager, sales director, and finally as Managing Director. During the course of his employment he spent a lot of time in meetings

with the Ministry of Health as his company supplied ethical pharmaceuticals to the NHS.

He told me only 2 stories about the NHS , the first was the constant complaints from politicians and the press about cuts in funding to the NHS, when in fact since its inception whichever government was in power, there has never been a cut in funding, it increases every year. The second concerned a discussion which he had with the Minister for health of the Irish government at the height of the “troubles”. He asked the Minister if the government backed the Sinn Fein ambition of uniting all of Ireland. The Minister recoiled in horror and explained it would be a disaster as if the NHS no longer

funded medical activity in the North of Ireland, that addition to the Irish government budget would bankrupt the country as a whole. He added that even if they could take it on the task of supporting the six counties DHSS would be way beyond their ability.

A landmark document for my forty years long surgical career.

Except when I worked abroad (in the tropics) I worked solely for the NHS. It was not the easiest organisation by which to be employed, but it never occurred to me that it was not a truly fine element of the UK’s support for its population. I look to my friends in the USA and see how the cost of health care has risen to obscene heights, which even the well-heeled find burdensome. This has been the most important and excellent social provision ever created in this country. Other states also have good systems (e.g. France) but none is guided by so humane an idea.

The coalition govt that came into power in 2010 started to make cuts to the NHS budget by not increasing it at the rate of inflation, as every govt had done before it. This in itself was belt-tightening and very difficult to explain as a cut. Then there has been a massive cut in beds. Hospitals are expected to run with no, or very few, spare beds at all. And when you look at the staffing situation, you can see how badly the NHS has been funded. Staff morale is low and people are leaving because they can’t live on the wages/salaries.

How come no mention of Nye Bevan? How can any treatise on the NHS not mention him ?

The British NHS was a great inspiration for our NHS in Portugal (SNS), created only in 1979. In 1958, Aneurin Bevan was invited by the Portuguese opposition to give a conference on the NHS in Lisbon. Dictator Salazar banned the event and ordered the arrest of the people who invited it. Our present SNS was not “copied” from the British NHS, which only served as one of its main models. Anyway, thank you, Beveridge and Bevan for your revolutionary healthcare system.