This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Glastonbury Festival. Music has brought comfort to many during lockdown, and while this year’s festival has been cancelled due to the Coronavirus pandemic, the BBC is celebrating by streaming four days of archive footage across its various channels and platforms on 25-29 June.

The festival, mounted by Michael Eavis at Worthy Farm in Somerset, was first held on 19 September 1970 (the day after Jimi Hendrix had died) when Tyrannosaurus Rex, who later evolved into T.Rex, were the headlining act. Tickets cost £1 (which included free milk from the farm) and publicity was fairly low-key: attendance was only 1,500.

To help celebrate the 50th anniversary of Glastonbury, I’ve curated a Spotify playlist entitled Archives Gold: 50 Classic Chart Hits from 1970. What is striking about this selection is the sheer variety of music from this era: pop, rock, soul, reggae, gentle singer-songwriter ballads, and much more. This listing is stuffed full of strongly melodic tracks which are well-known and well-loved by many pop fans today. Anyway, I musn’t get carried away! I’ll return to my narrative.

A multi-layered story

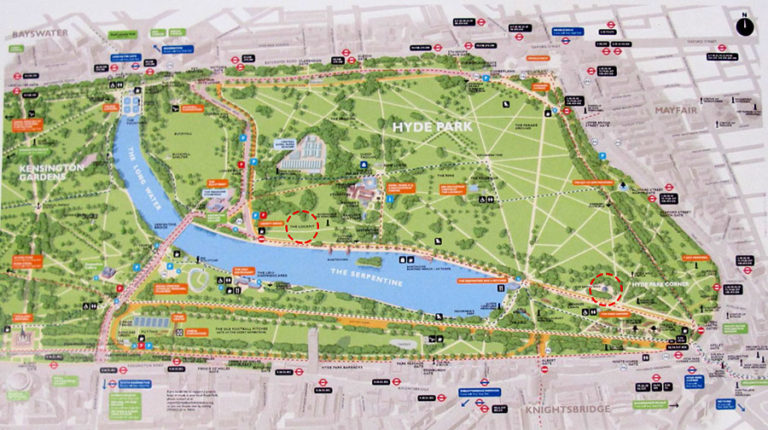

It’s very interesting to look back at the early days of music festivals. The National Archives holds a fascinating file which enables us to do just that, from the British perspective, and with the setting being a famous Royal Park in London. It is an Office of Works, Royal Parks Division file entitled ‘The use of Hyde Park for pop concerts’, covering 1968-1969[ref]The National Archives: Catalogue reference: WORK 16/2340[/ref]. It is a story of clashing cultures, and a generation gap, but there are many other layers to it. There are elements of altruism, well-honed public relations, and naivety.

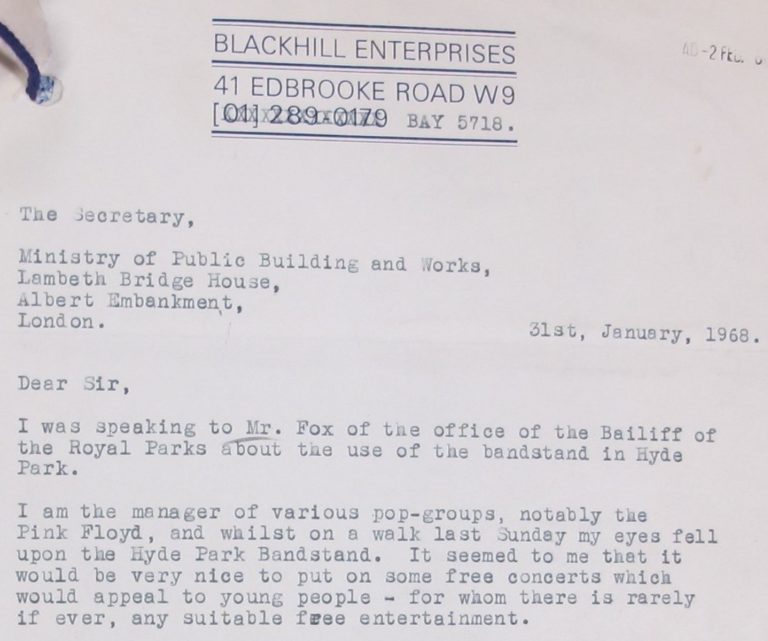

Our story begins with a letter from Peter Jenner, now a well-known and highly esteemed music producer. After gaining a First Class Honours degree in Economics at Cambridge University in 1963, Jenner became a lecturer at the London School of Economics at the age of 21. But he was attracted by huge explosion of creativity in the pop scene, and in 1966 he co-founded a music management company, Blackhill Enterprises. And on 31 January 1968 he wrote in to the Ministry of Public Buildings and Works.

Some of you may be familiar with the bandstand at Hyde Park. It’s a very pleasing structure, as you can see in the below image.

Mr Jenner continued to make his case. He had already been in touch with an official concerning the matter, a Mr Fox.

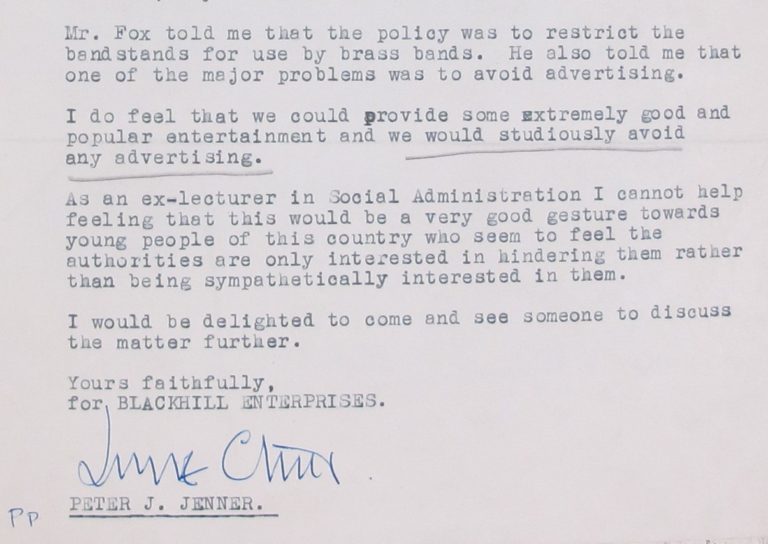

We can see that Peter Jenner is at pains to win over the Ministry officials, and to assure them that Blackhill Enterprises will avoid advertising, which would have been out of keeping with the protocols of managing Hyde Park.

So how was this request received? Well, Jenner received a reply from a Mr R Phillips in the Ministry of Public Buildings and Works. It was very courteous, but Mr Phillips turned him down. The key message was: ‘We receive requests of this nature fairly regularly, but I am afraid that it is the Department’s policy to limit musical performances in the Royal Parks to those given by established military and civilian brass bands’.

Undaunted, Peter Jenner then began to lobby a young London Labour MP Ben Whittaker, Robert Melluish, the Minister for Public Buildings and Works, and Lord Kennet of the Ministry of Housing and Local Government, and through these contacts Jenner managed to build support in favour of experimenting with a concert in the park.

Concern from government officials

Meanwhile, senior civil servants at the Ministry of Housing and Local Government were disturbed at the prospect. An internal discussion in February 1968 appears to have been prompted by further lobbying by Mr Jenner, either directly or indirectly. Mr Phillips wrote: ‘we must consider the effect of these concerts on the park itself. It is regrettable but undeniable that pop groups attract more than their fair share of the rowdy element, and the prospect of clashes between them and the more sedate park visitors is not attractive’.

Mr Phillips’ colleagues, N T Downing and L Potts, were in agreement. Downing wrote ‘the only place where people can get a bit of peace and quiet is in the Royal Parks’ and Potts commented ‘Heaven preserve the Parks from being turned into a sort of extension of Carnaby Street. They are needed to escape from the so called “Swinging London”’.

Generation gap

It would be easy to portray these reactions as stuffy and reactionary. But we need to understand the perspective of these officials. For one thing, they were simply doing their job, which they saw as preserving the sanctity of Hyde Park, with its special status as a Royal Park. But the broader context is that there was more of a gap between young people and their parents or grandparents in the 1960s than there is nowadays – the generation gap was wider.

To draw on my family memories, and to illustrate this point, I recall my Grandma Dorothy, telling me that she liked The Beatles when they were ‘wholesome’. She was referring to their mop-top period, when their appeal went wide across society. But by 1967/1968 the psychedelic Beatles, with their drug references and ever longer hair, became rather more disturbing to the older generation, and my Grandma was obviously implying that she wasn’t keen on the later manifestation of the ‘Fab Four’.

Nowadays, for the sake of argument, it wouldn’t be that unusual to see a grandparent wearing a Rolling Stones or Lynyrd Skynyrd t-shirt or to be actively supporting a grandchild who is an aspiring rock musician or singer songwriter. But in those days, as a generalisation, there was more of a gap. Mr Phillips is being dutiful when he refers to the needs of the ‘more sedate park visitors’.

Now back to the narrative. Civil servant R Barrow was sympathetic to the proposal for a pop concert in Hyde Park. In a letter of 29 February to the Minister, Robert Melluish, Barrow advised that ‘we should proceed with some caution’ – he was concerned about reaction from some sections of the public and he mentioned that the experience of the Greater London Council (GLC) of running pop concerts in their parks had not been entirely happy.

The GLC had found that such concerts tended to attract gangs of noisy and unruly youngsters, and also the amplification of pop music had to be kept within reasonable limits. But Barrow suggested that, as a first step, ‘we experiment with two of these pop concerts in Hyde Park, just two concerts and then we’ll be in a better position to judge whether or not we can go ahead with more’. Furthermore, he suggested that Mr Jenner could visit the Ministry to meet and have a discussion with us. The Minister agreed, and on 14 March the Bailiff of the Royal Parks, Mr Downing and L Potts (the officials mentioned earlier), met with Mr Jenner to discuss his proposals for free concerts on the bandstand.

Breakthrough

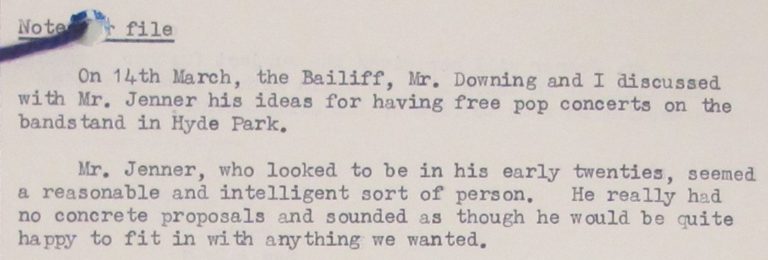

This extract from the Royal Parks file written by L Potts from the file shows how this meeting transformed prospects for pop concerts to be held in Hyde Park.

These comments from L Potts show that he’s been completely won over by Peter Jenner and, after all, Potts had been one of the fiercest critics of the proposal in the first place.

Mr Jenner must have had a great deal of charm. It was agreed that the policing of these concerts would be light touch and discreet and so advertising for the first concert went ahead, on the afternoon of Saturday 29 June, featuring Pink Floyd and Tyrannosaurus Rex. It was considered very successful and paved the way for more gigs.

The concert location on that June day was in the Cockpit (in the middle of the park, close to the Serpentine) – which has been described as ‘a naturally sloping amphitheatre’ featuring some lovely trees. This was to become the regular venue – as I understand it, the bandstand was only used once (due to bad weather) for a concert headlined by The Move, but it was felt to be a less satisfactory location. It considered too open a spot and there were many complaints about noise.

Do you want to know the rest of the story? How fans of the Monkees caused great concern to the Royal Parks Bailiff? How problems began to mount with staging the pop concerts in Hyde Park? How the whole phenomenon was debated in the House of Lords? How the Rolling Stones stepped in to compensate the Park authorities for damage caused to trees by fans when the Stones played their famous gig in the Park on 5 July 1969?

Then you’ll need to listen to my podcast, Culture Clash? Pop in a Royal Park.

This year we have time to take stock of the past, and it is fascinating to explore the origins of large pop and rock festivals – and amazing to consider that some of these events were free, before commercialisation became the norm. Archives can enrich our understanding of how society was changing in the 1960s.