This blog continues our series commemorating the centenary of the Battle of Vimy Ridge.

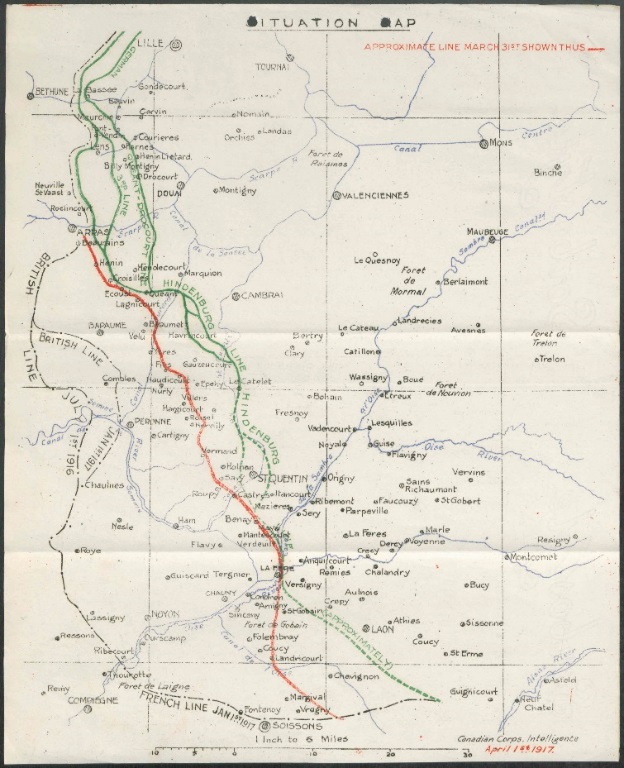

Situation map – German withdrawal to the Hindenburg line (The National Archives, catalogue reference: WO 95/1049/9)

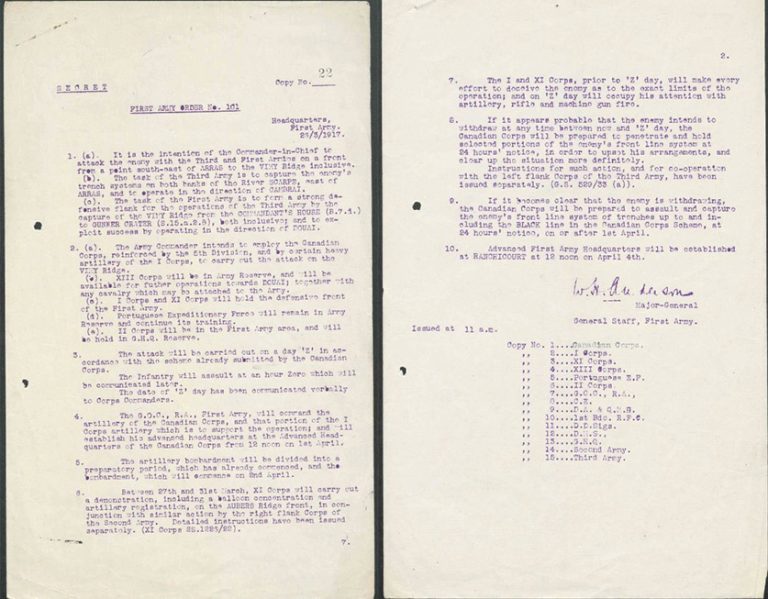

The Arras offensive of 1917 was divided into ten distinct actions, comprising sizable battles along with flanking and subsidiary attacks. The first two actions of the initial phase – the simultaneous battles at Vimy Ridge to the north of Arras and astride the river Scarpe in the centre – took place between 9 and 14 April. The former was to be the Canadian Corps’ contribution to the offensive – the first time all four Canadian divisions had fought together – and was directed towards the formidable defences on the high ground. The original purpose of the attack was to form a defensive flank for the operations of the Third Army to the south but, given the German withdrawal to the Hindenburg Line the month before, its operational importance grew in magnitude. Possession of the ridge allowed German forces a commanding view of British and Commonwealth positions below; its capture would not only alleviate this issue for attacking forces, but would put that same advantage in the hands of the British.

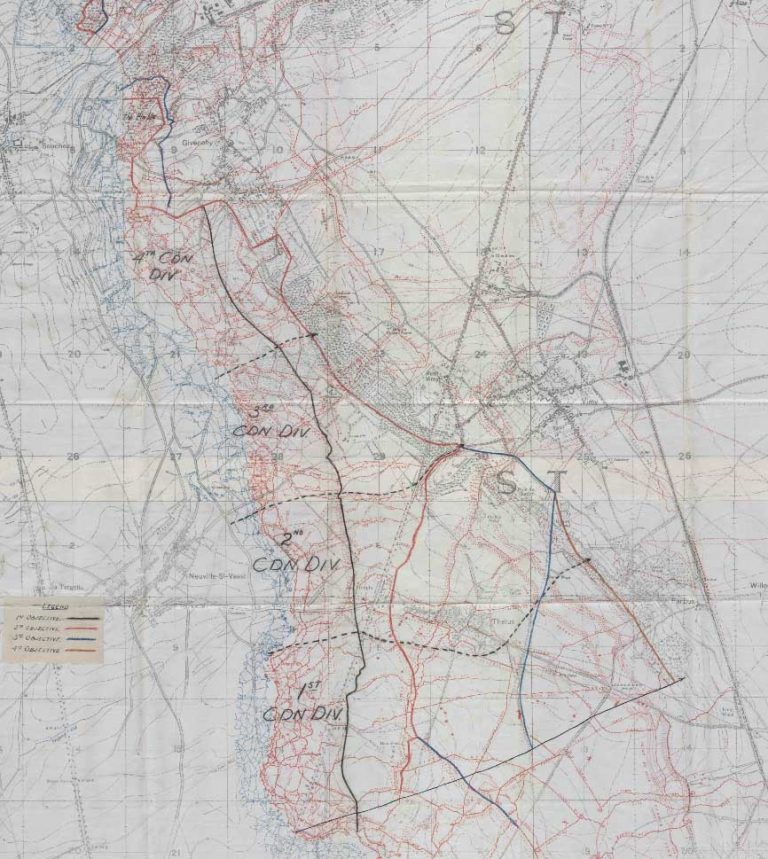

A map of the Canadian Corps military objectives, from Canadian Corps General Staff war diary, April 1917 (The National Archives, cat ref: WO 95/1049/9)

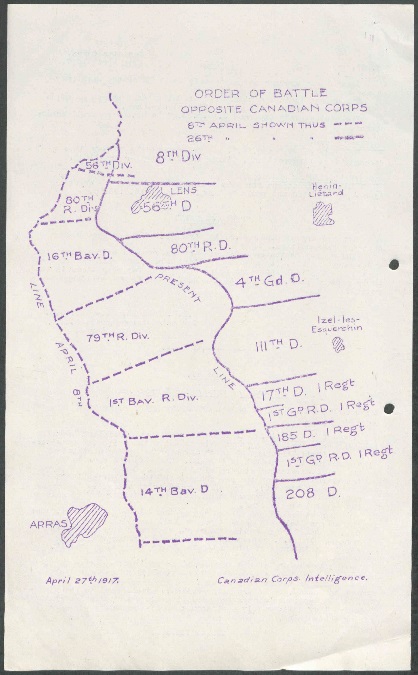

Order of battle showing the lines on 6 and then 26 April. The map also shows the German regiments behind the lines at both those dates. It is dated 27 April and was produced by the Canadian Corps Intelligence (The National Archives, cat ref: WO 95/1049/9)

These operations had been planned in principle since the end of the previous year and very careful preparations had been made in respect of the training of personnel and the accumulation of artillery and the materiel of war. Furthermore, the actual attack on 9 April was the culminating thrust of a phase of operations, including a large number of raids and an incredibly destructive artillery bombardment. The steady wearing down of the enemy’s morale and defences, combined with the diligent training and preparation conducted by the Canadians, set the stage for a climactic and decisive battle.

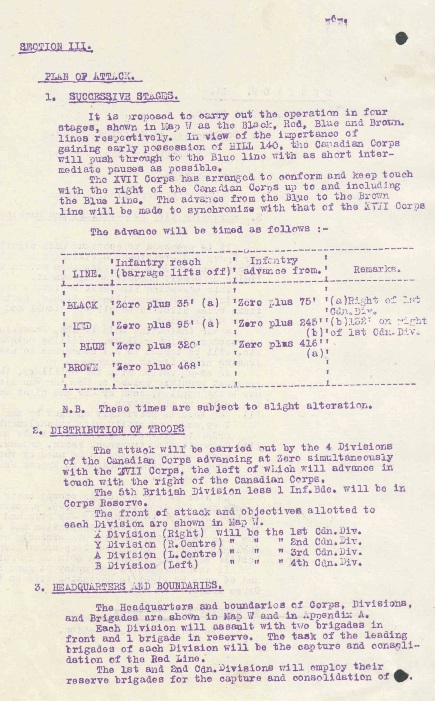

As in any major offensive operation, objectives were set for the Canadian Corps, but these were specific and limited in their scope. Some were common to the divisions, while others were assigned to particular sections of the line. They consisted of two primary – a black and a red line – and two secondary – a blue and a brown line.

The first of these meant passing through the German frontline to a depth of around 700 yards. Once the ground was taken, the 3rd and 4th divisions would reform German support trenches into their main line of defence. The red line stood between 400 and 1000 yards ahead of the first objectives and represented the farthest goal of the 3rd and 4th divisions.

Proposed plan of attack showing the four different stages and timings of the advance (The National Archives, cat ref: WO 95/169/6)

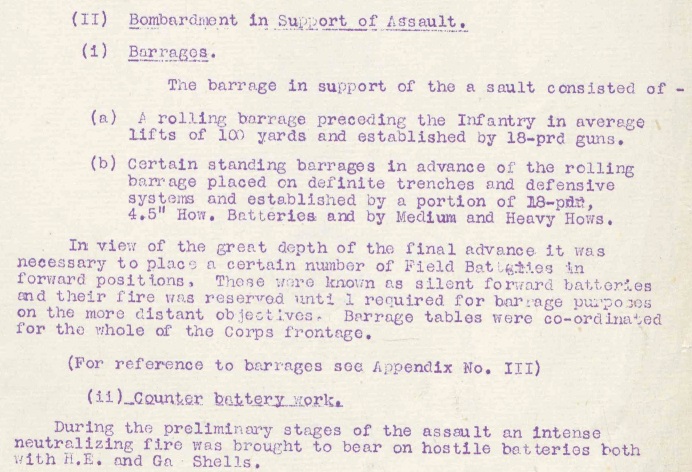

Bombardment in support of the assault (The National Archives, cat ref: WO 95/1049/10)

The blue and brown lines ran between 1,200 and 4,000 yards in front of the red line and were exclusively the responsibility of the 1st and 2nd divisions. Collectively, these objectives incorporated an extensive and intricate system of trenches, dugouts, tunnels and strong points, which the German army had spent two years constructing. Their taking was to be intimately bound to the artillery fire plan, which would lift from each objective just before the infantry arrived.

Artillery preparation was understandably meticulous, beginning 20 days in advance and increasing in intensity as the day of the attack approached, all the while never giving away the full weight of firepower available. Both wire and strong points were kept under barrage, weakening German defences as well as the morale of those stationed at the front. Fire in support of the assault was similarly well planned, with a rolling shrapnel barrage due to fall in 100 yard lifts and standing barrages on defensive systems ahead of the advance. More than 200 machine guns were also to be brought to bear on the relatively narrow front, with 150 providing an indirect barrage and supporting fire; 130 due to be carried by the assaulting brigades for use in consolidation; and a further 78 held in reserve. The heavy artillery and companies of the Special Brigade Royal Engineers (which is to say gas companies armed with Livens Projectors) were to use high explosive and gas in counter-battery work to suppress German artillery.

Tanks, too, were allotted to the Canadian Corps in support of their operations. Having seen their debut at Flers-Courcelette on the Somme just seven months before, eight were given the task of working around the defences of Thelus, which sat between the 1st and 2nd divisions – the two with the furthest to travel. Despite their promise on the battlefield, given the limited number and reliability issues associated with tanks, all artillery and infantry planning was made without reliance on their contribution.

Reconnaissance by the Royal Flying Corps’ 16 Squadron and No.1 Kite Balloon Company informed the plan of attack, while elaborate communications plans using buried cable, wireless and visual receiving stations for Forward Observation Officers of the artillery mitigated against complications on the day. Mining was used not only offensively with the intention of demolishing German strong points, but also to produce nearly four miles of tunnels and subways for the infantry coming forward for the attack and to evacuate the wounded.

Canadian Field Artillery bringing up the guns. Vimy Ridge, April, 1917 (Library and Archives Canada – MIKAN 3521867)

Everything was in place for the hour of the assault: 5.30am on 9 April, 1917. The preceding hours of darkness aided by cloud cover had permitted the infantry to file forward unobserved into their jumping off positions, many of which were clearly observable to the enemy in daylight. Had this movement been witnessed, an enemy barrage may have broken up the assault wave with serious casualties; as it was, the positions were gained without notice. In the half-light of zero-hour under a cold overcast sky, when manoeuvre was still largely obscured from the enemy, the intense bombardment opened with sudden fury and the advance of the infantry began.

First Army Order No. 101 [for the attack on Vimy Ridge] signed by Major-General W.H. Anderson, 26 March 26, 1917 (The National Archives, cat ref: WO 95/169/7)

This blog was developed under a collaborative agreement between Library and Archives Canada and The National Archives. Look out for the next blog in the series on 12 April.

A wonderful story and great detail on the maps of the battlefront.