Last October, I attended a conference on ‘Résistance et Dissuasion’ – the Resistance and nuclear deterrence, held at the French National Library. The conference was accompanied by an exhibition for which The National Archives had provided documents from our collection. One of the panels told the tale of a secret mission sent to Norway in 1940 to rescue a rare commodity: heavy water.

Heavy water (deuterium oxide) was essential to the experiments conducted in Paris by Frédéric Joliot-Curie and his team, racing against time to develop a nuclear bomb.

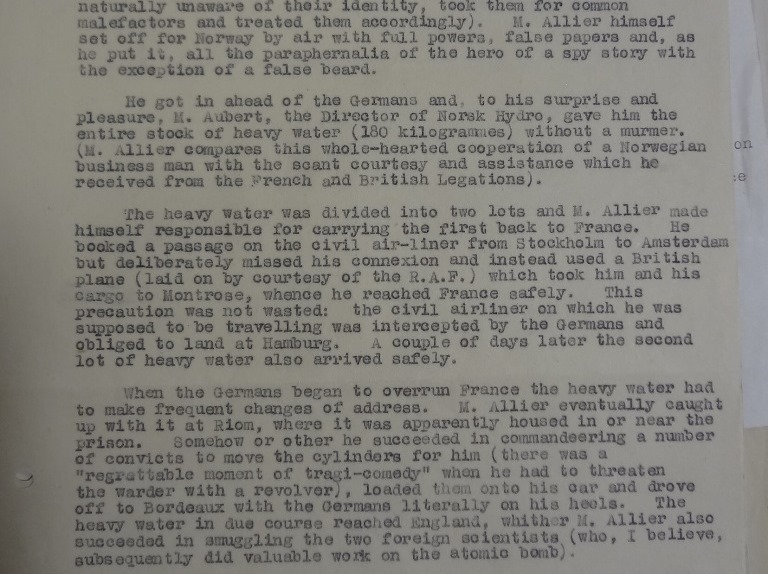

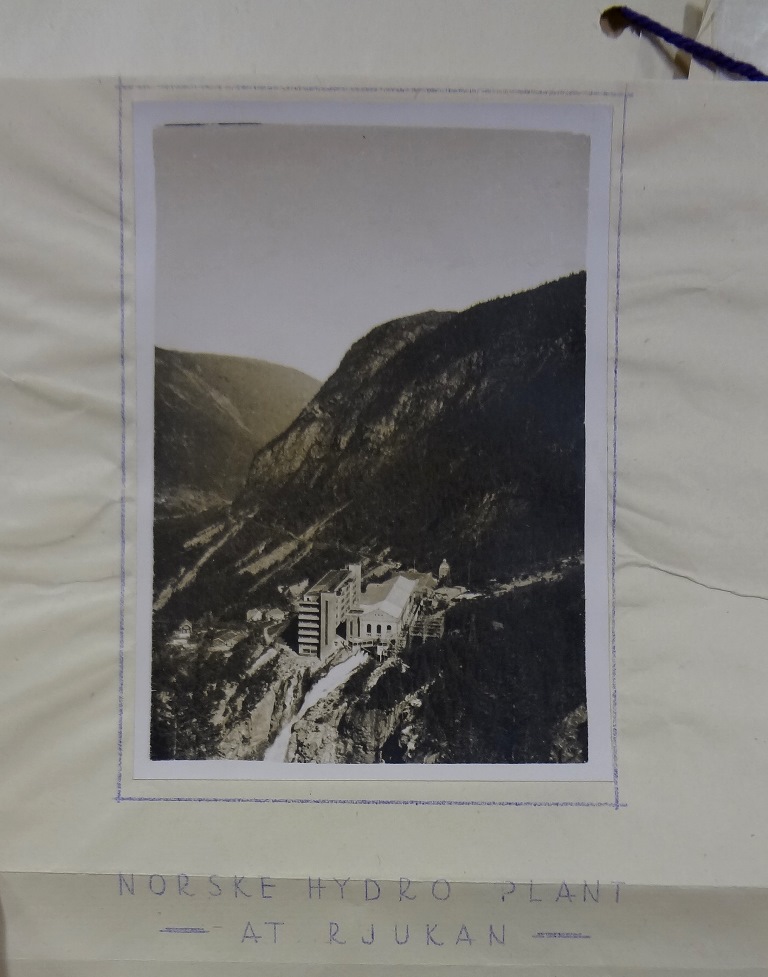

In 1939, it became apparent that the Germans were trying to get hold of the heavy water produced in Norway by the Norsk Hydro-Elektrisk Kvaelstofaktieselskab factory (Norsk Hydro for short) in Vemork, about 65 miles west of Oslo. The French Minister of Armaments, Raoul Dautry, approached Jacques Allier, a member of the French intelligence service. Before the war, Allier had worked at the Banque de Paris des Pays-Bas, who held most of Norsk Hydro’s shares. He was asked to negotiate securing their entire stock of heavy water (180 kilos) and to bring it back to France. According to a note written after the war, based on a conversation with Allier, he then ‘set off for Norway with (…), as he put it, all the paraphernalia of the hero of a spy story with the exception of a false beard’ (CAB 126/171).

Allier managed to secure the whole stock of heavy water and transported it to France, where it was entrusted to Joliot-Curie. When the Germans started marching onto Paris, the heavy water cylinders were sent to Clermont-Ferrand, in central France, where they were kept in the vault of the French National Bank. They were then hidden in a prison cell in Riom. When it became clear that France would fall, Allier enlisted inmates to carry the cylinders to his car (‘there was a “regrettable moment of tragi-comedy” when he had to threaten the warden with a revolver’) and left for Bordeaux. There, on 16 June 1940, he met with Joliot-Curie and two of his staff, Hans von Halban and Lew Kowrski, and asked them to accompany the precious cargo to Britain (AB 1/229).

Joliot-Curie refused to leave France so Halban, Kowarski and the heavy water embarked on SS Broompark on 19 June (BT 389/5/203). They both joined the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge, and were able to continue their research in Britain (AB 1/229).

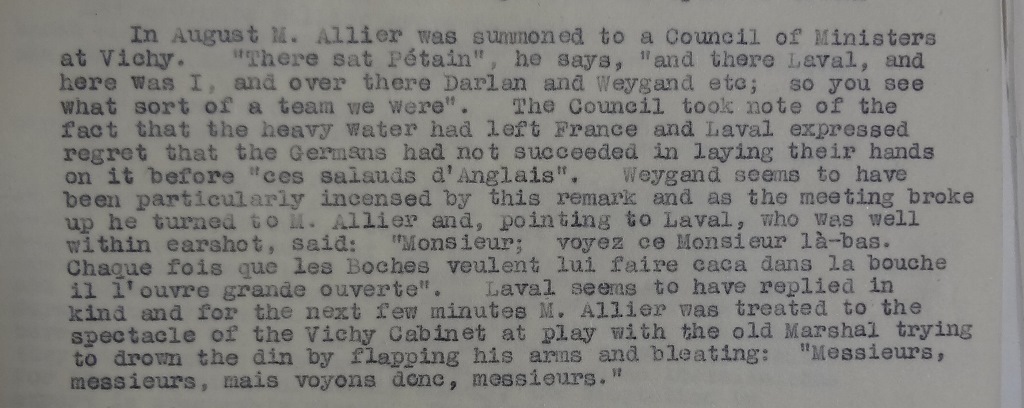

As for Allier, he was summoned by the Vichy Cabinet in August 1940, and had to confess that the heavy water had left France. This led to a rather farcical situation. The announcement provoked an argument between ministers, a number of rather crude insults were exchanged and he ‘was treated to the spectacle of the Vichy Cabinet at play with the old Marshal trying to drown the din by flapping his arms’ (CAB 126/171).

It wasn’t the last time heavy water and the Norsk Hydro plant would prove to be an issue during the war. According to a report on operations carried out by SOE in Norway,

‘In July 1942, it was decided to be of the highest importance that the existing stocks of “heavy water” (deuterium oxide), at the Norsk Hydro Works, Vemork, Norway, should be destroyed, together with the plant essential for its production.’ (AIR 8/1767)

A first attempt was made in the autumn and winter of 1942. Operation Grouse started in October 1942 when a Special Operations Executive (SOE) advance party of four officers and NCOs of the Norwegian Independent Company were parachuted about 30 kilometres from the Norsk Hydro plant. They established communication on 9 November and, ‘working at an altitude of some 1200 metres and a temperature continually below zero centigrade’, started transmitting reports on weather conditions and on German defences in the Rjukan area, where the plant was located.

Operation Freshman started on 19 November 1942, when two aircrafts left Scotland, each towing a glider. The operation had two objectives: the destruction of existing stocks of heavy water and of at least part of the plant, and the collection of samples of the precious liquid (AIR 20/4527). The geographical location of the plant made the operation extremely hazardous.

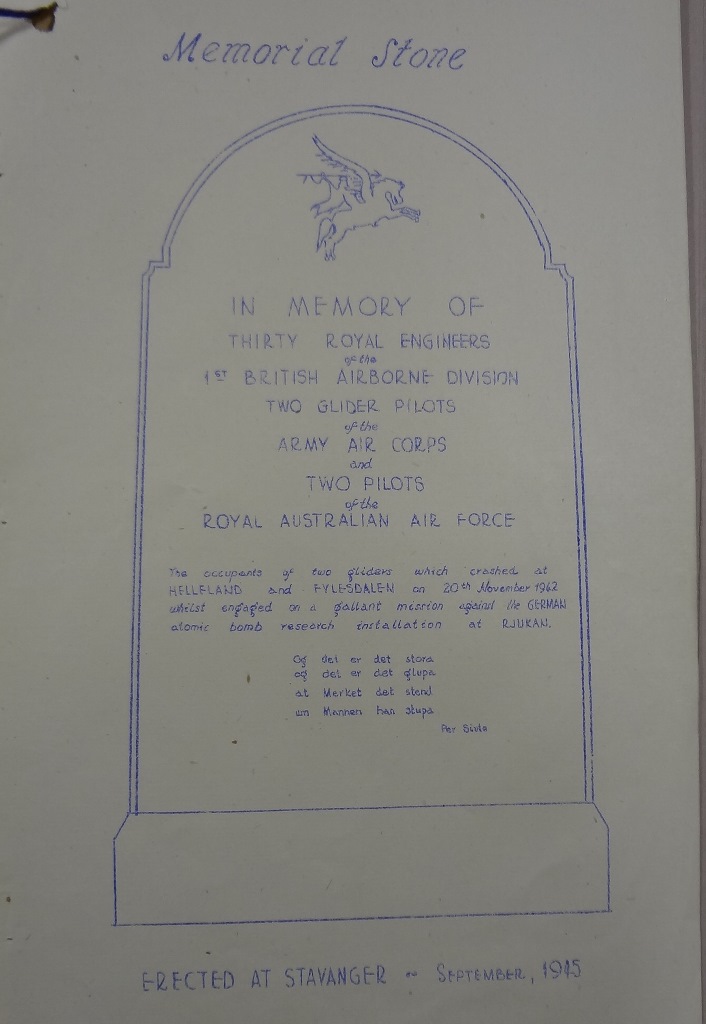

One of the aircrafts and both gliders crashed. All the survivors were caught by the Germans, tortured and executed (WO 331/16). A memorial stone was later erected in Stavanger to commemorate their heroic attempt (AIR 20/11930). The advance party, however, remained undetected, and continued to transmit information. Because of the failure of Freshman, however, the Germans were aware that the plant was a target and increased their defences. Grouse became Swallow, and ‘continued their watch and signals amidst snow and ice, short of food and with failing power in their W/T set’ (AIR 8/1767).

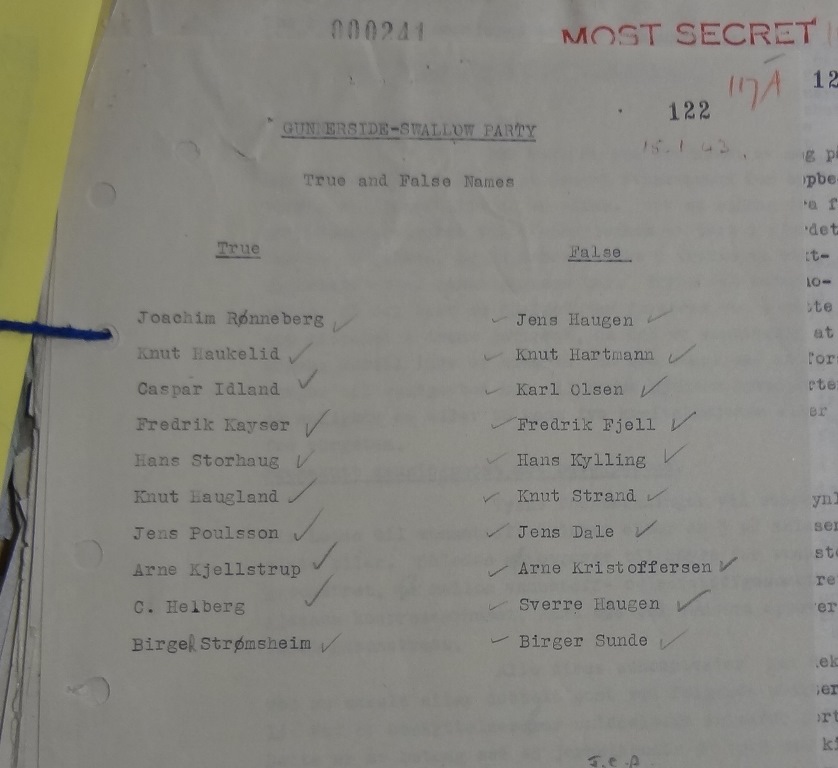

A second attempt, this time successful, was made in February 1943: Operation Gunnerside. Six officers and men from SOE, specially trained Norwegian personnel, were parachuted about 30 kilometres from Swallow’s camp. The two parties met up in a hut on the evening of 23 February and, after travelling for 60 kilometres, attacked during the night of 27/28 February.

A report transmitted from Stockholm shortly after the operation stated:

‘They came in civilian clothes to Rjukan, but when they appeared at the factory they were clad in British Uniforms and had revolvers. They told the workers in perfect Norwegian to go up in the seventh floor of the factory building where no harm would come to them. Then they went up to the vital machinery of the factory, placed their explosive charges there, pulled out the fuse and lit it. The destruction was complete as all the vital parts of the machinery were blown to pieces.’ (AIR 8/1767)

It was estimated that the plant would be put out of action for between eight and 12 months. Five of the Gunnerside/Swallow men crossed the Swedish border, and five remained behind, including the wireless operator who kept transmitting. The operator reported that General Falkenhorst, the commander of German troops in Norway, had visited the plant shortly after the attack, ‘which he at once ascribed to personnel from Britain’ and declared it was ‘the most splendid coup [he had] seen this war.’ (AIR 8/1767)

As early as August 1943, however, the Vemork plant had been repaired and production had recommenced. As it was still vital that the production of heavy water should be stopped, a choice had to be made between yet another sabotage operation or a straightforward bombing attack. A bombing attack seemed to be the only way to ensure substantial damage, but the Deputy Chief of Air Staff didn’t think it would work. The plant was quite small and a low-level attack was impossible because of the hills surrounding it.

As SOE was unable, or unwilling, to carry out another attack, the Americans were informed of the situation. The USAAF attacked on 16 and 18 November 1943, and Swallow reported on 30 November: ‘Vemork completely destroyed (…). Will hardly be able to start production again during the war.’ The battle for heavy water had been won (HS 2/187).

Long after the end of the war, when Joliot-Curie was not only a nuclear scientist but also ‘an international communist’, MI5 operatives noted that ‘it [was] impossible to give in a few lines an idea of [his] scientific work’ (KV 2/3687). The SOE did give it a good shot in 1942: the application of heavy water, they said, was ‘both Churchill’s and Hitler’s real secret weapon and bands of scientists [were] engaged in a race for the final result.’ (HS 2/184)

While the American raid gave the Vemork plant the coup de grace, scientists like Halban, Kowarski or Joliot-Curie couldn’t have remained ahead in that race without the men involved in operations Grouse/Swallow, Freshman and Gunnerside. As the Ministry of Economic Warfare put it in April 1943, ‘I hope you will agree with me that the story is a particularly good one.’ (CAB 126/171)

An excellent blog post. Very interesting and informative with plenty of file references to follow-up.

Thanks

I attended also the conference in Bordeaux in 2017 and gave at this occasion a lecture about Paul Timbal’s memoirs. He was a Belgian diamond banker who fled with a fortune of diamonds from Antwerp to Bordeaux and travelled with the Broompark. His report, which was published in 2014, is a principal source about the journey of this ship, transporting the diamonds and the heavy water.

I’m always ready for further comments and collaboration.

Bruno Comer Weststraat 35 8340 Damme Belgium

Was there any evidence of research into heavy water post world war 2 on Merseyside? Aeronautical engineers who originated from Canada/US working on atomic water projects?

In the ORB for 138 Sqn (Air 27/856/1 Page 84) there is an indication that Operation GROUSE II failed on 12/13 September 1942 as the result of one of the aircrafts engines failing over the North Sea and landing at a diversion airfield – RAF Peterhead. Is there a crew / passenger manifest available to view via the archive for this particular Operation.

Dear Mark,

Thank you for your comment.

For help answering questions like this, please use our live chat or online form.